Looking Back at Looking Back

Michael Kackman / University of Notre Dame

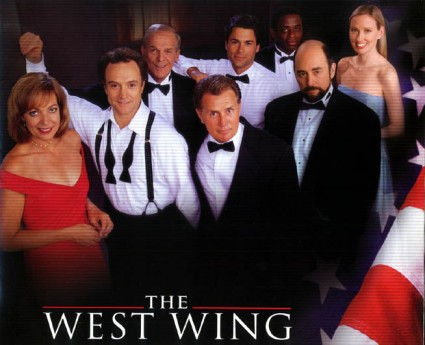

A familiar conceit runs through most of Aaron Sorkin’s television series, from The West Wing, to Studio 60 on the Sunset Strip, and most recently The Newsroom. Each of these shows is organized around creative, smart, and insightful characters who rail against mediocrity, ignorance, and petty self-interest. In some of these programs’ most satisfying moments, these characters’ frustration boils over, and we see them finally knock the troglodytes back on their heels. This trope arguably worked best on The West Wing, whose shadow Presidency was liberal porn for disgruntled Democrats through the Bush years. The late night comedy setting of Studio 60 was ultimately incommensurate with the ambition of its lead characters to save television for all those who were mad as hell (an outrage that found a more apt arena on The Newsroom), but the narrative pleasures of all three series were more alike than different. In each, smart men did smart things for the common good.

Such was the tone in the room at the first Flow Core Conversation at this year’s conference. It was an impressive lineup: journeyman writer and director Michael Zinberg (The Bob Newhart Show, WKRP in Cincinnati, The Good Wife, and dozens of other prime-time directing credits), Howard Rosenberg (25 years as the LA Times’ chief tv critic), and the beloved TV auteur David Milch (Hill St. Blues, NYPD Blue, Deadwood, Luck), in a free-wheeling and lively discussion moderated by television scholar and former director of the Peabody Awards Horace Newcomb.

It was an engaging conversation, and one that led both to familiar moments of recognition and some genuine insights. For starters, the participants all lived up to their reputations as smart, funny, and reflective about both themselves and the medium they’ve been working in and around for their entire careers. Rosenberg invented a position for himself as a newspaper TV columnist first in Louisville and eventually at the LA Times, self-deprecating that “the bar was so low, it was almost impossible to fail.” In the process, he helped to reinvigorate popular TV criticism, an omnibus task that required a decathlete’s diverse skill set. Television is, after all, in Rosenberg’s words, “about everything. I could write about politics, I could write about sports, I could write about housekeeping.”

For his part, Michael Zinberg began working in local television in his home state of Texas, and moved to Los Angeles in 1968 in hopes of writing and directing. Working his way up from usher and gofer, he built his early career at MTM Enterprises, most notably as writer, director, associate producer, and eventually producer of The Bob Newhart Show. At several points in the conversation, he made TV scholars’ hearts flutter just a little, as when he reflected on the 1973 writers’ strike and the subsequent reorientation of the industry that began at Lorimar, Tandem, and MTM: “it was the best thing that ever happened to TV.” Zinberg went on to characterize the networks as dominated by risk-averse non-thinkers, and asked the scholars in the room to pay more attention to the impact of ownership and the FCC’s Financial Interest in Syndication rules. “There are no more Norman Lears, no more MTMs, because the networks own everything. Creative opportunities are due more to the diversity of outlets than anything.” The industry is much less favorable to independent production today than it was in the 1970s, because “the studios own damn near everything.”

Much of the conversation circled around questions of creative agency, and despite their obvious thoughtfulness about the limitations of the corporate system, they largely agreed that television remained a medium in which creative people could find a voice, and an audience. As imagined by these industry figures who got their start in the 1970s, television remains more or less the same storytelling medium it has always been. Zinberg insisted that “once TV became the primary storyteller for the American public [in the early 1960s], not much has changed.”

It’s likely that no one embodies the fierce charisma of the idealized TV writer more than David Milch, who came off as the enfant terrible of the group. His first gig was wrangling the peanut gallery on The Howdy Doody Show: “There was a kid blowing his nose into his hand, and that was disgusting. So I crossed over there, and knocked out his two front teeth. That was my first job in TV.” True or not is irrelevant; the story works. When discussing the impact of new distribution technologies like Netflix on the working life of a writer-director, his voice dropped, he leaned out over his glasses, and he growled that “the jungle will find out what you’re doing there.” Milch could clearly be both wildly imaginative and deeply insightful, as when he reflected on the twin dramas of watching Jack Ruby shoot Lee Harvey Oswald live on television in 1963 and the grisly ISIS beheadings of this year. The fundamental role of television storytelling, fictional or otherwise, he said, is to create a world with which “you can coexist emotionally,” balancing fascination with repulsion. Those horrific murders ruptured that balance, but in doing so revealed something about our relationship with television, and with Milch’s work in particular. He went on to characterize his HBO series Deadwood succinctly; it was an experiment about “what happens when a lie is agreed upon.”

[youtube]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pv_viK8qOfw[/youtube]

Perhaps because they were all invested in an ideal of TV authorship and creativity to which they’ve devoted most of their lives, none of these longtime pros seemed especially willing or able to be critical of how the industry defines, measures, or rewards success, or the kinds of representations of American life that circulate on it. Maybe it’s because they recognize that their biggest commercial successes weren’t necessarily those that they felt were genuine creative achievements; maybe it’s simply well-earned cynicism about the corporate decision-making machine. Regardless, even when pushed by the audience or by Newcomb, who raised the issue of television’s waning role as what he has enduringly theorized as a cultural forum (“we’re losing the sense of a shared experience, and satisfying only personal tastes; something has altered the relationship, the ecology of the medium. We need to talk about this a little bit”), they had little response. Milch was mostly interested in reflecting on the nature of creativity, a mad waltz he knows well; Rosenberg recapitulated the vague progressivism of TV executives’ own self-image when he credited Modern Family with helping to change the landscape of LGBT rights; Zinberg was more reflective, observing that “diversity is something that is spoken about in Hollywood with great sincerity. By and large, the real decision makers are chicken-hearted, and when it comes down to it, they will make decisions that will baffle you. Some of us raise hell about it. Some of us don’t.”

Near the end of the conversation, Newcomb reflected on the centrality of network television to his experience of the civil rights movement growing up in the South, observing with regret that “we could have a great show about race today, but the only people who would watch it would be those who wanted to watch it, not those who needed to watch it.” This kind of cultural forum argument may have once seemed to be a descriptive observation (“this is how television works”), but it’s clear that for many of us – Newcomb included – it’s also an ethical argument (“this is how television should work”). For all their insights, and for all their obvious good will and generosity, this wasn’t a line of inquiry that the panelists could speak to. It was clear that their most meaningful relationship with television was through the muse of fictional storytelling – which is, perhaps, enough.

And yet, just as with The West Wing or The Newsroom, it seems a little empty to simply revel in the (genuine) pleasure of watching smart guys demonstrate their chops. Their magnetic personalities and wry disaffection make them great storytellers of lives spent in the Hollywood trenches, but I have to think there’s more to the conversation than that. Because the panelists were all very successful older white men at the end of their careers, there was very little friction about how we define such things as “success” or “creativity”, and there was little space to critique just who has the opportunity to pursue those virtues. By not asking hard questions about who holds that power, and why, the panel reinforced the sense that despite its capricious economism, the TV industry is ultimately a meritocracy within which the truly creative can thrive. I found myself wishing that the panelists had been participating in some of the other conference roundtables (like the one on job opportunities for women, people of color, and women of color in the industry), or even the Twitter backchannels about the unselfconscious nepotism that so clearly gave several other industry panelists their foothold in the business. Milch, Zinberg, and Rosenberg are all obviously smart and thoughtful, and they would likely have had even more to say in a conversation that pushed them a little off the auteur center.

So, too, for the representation of our field in these Core Conversations, which act powerfully to define a perceived center and its margins. Of the eleven invited panelists who participated in them, ten were from the industry, and ten were white men. As we look ahead to future Flow conferences, perhaps we can embrace the broader history of our field – a new discipline founded largely by a generation of feminist scholars who helped make television an object of legitimate study precisely by exploring its cultural illegitimacy. This observation was discussed very thoughtfully in at least one roundtable, and would make a fantastic Core Conversation in the future. Our field was shaped heavily by outsiders; they deserve to be at the center of the histories we tell.

Image Credits:

1. Core Conversation 1

2. The West Wing

3. MTM Enterprises

Please feel free to comment.

Great tips to play card game at this entertaining Junction.Thanks for suggest me about this exciting spider solitaire through this post and now i am addicted to play this always at my free times.Easiest way to open or play with some special skills.