No Rerun Nation: Canadian Television and Cultural Amnesia

Serra Tinic/ University of Alberta

“And reruns all become our history.” Goo Goo Dolls, Name

I realized at the end of this semester, that for over a decade, the above lyrical excerpt has been the single constant feature of my introductory television studies syllabus. I originally used it as a subtitle to signal the centrality of television to our sense of community, sociality, and cultural memory. Reading it now, it helps explain the fact that I actually teach very little about Canadian television despite being located at a Canadian university. Reruns of Canadian television drama are few, fleeting, and scattered (or more accurately: ‘sprinkled’) across the spectrum of cable and specialty channels. My students have no memories of a national television culture and, in the absence of tangible video evidence, I would have to resort to pantomime to discuss domestic drama circa the 1970s or earlier. As it is, I sound like I’m channeling Grandpa Simpson every time I try to explain television from the 1980s. Given Canadian broadcasting policy’s obsession with cultural cohesion and nation building, I can only describe this as an “epic fail,” to quote the young ‘uns.

[youtube]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FteZimbz59I[/youtube]

This column ruminates on the role of reruns and their connections to time, place, and cultural discourse. Readers will recognize the title’s homage to Derek Kompare’s book Rerun Nation1 and Martin Roberts’ earlier Flow column, “This was England” . Both authors provide exemplary insights into how ‘vintage’ programming constructs dominant discourses of heritage as it relates to both a sense of national community as well as specific national broadcasting structures and industrial practices. Moreover, they provide important interventions into television studies, in general. Too often, we focus on ‘the new and original’ and relegate syndicated programming to the realm of media history. Reruns, however, compel us to consider how televisual constructions of/from the past resonate and are interpreted within the present moment. They play a critical role in generational memory and social critique. The Canadian television story is the antithesis of the British and American industrial examples. It is a narrative of absence. My attempt here is to merely raise new questions about nostalgia and television: Is nostalgia necessarily a conservative form of remembering? Can nostalgia be productive?

The scarcity of Canadian reruns is a result of the tensions between the economic imperatives and cultural objectives that have long marked national broadcasting and the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (CBC) in particular. Canadian private broadcasters have not, until recently, contributed very much to the production of domestic drama. Therefore, the evolution of a rerun culture largely depends on access to the national public broadcaster’s library of programming. And the contractual obligation to pay royalties to the production crews and creative teams dating back to the early years of in-house drama production have made reruns a less attractive option to original domestic programming and international imports. Reruns are simply seen as too expensive within the overall cost-benefit analyses of industry decision makers in a small-market nation where the domestic audience will never be large enough to recoup expenses. This stands in marked contrast to the American industry where reruns provide relatively inexpensive programming and are integral profit generators in offnet scheduling. Profit motives and market size have also delayed the transfer of early Canadian drama series to DVD format. And this is to say nothing of the cost of film and video restoration to contemporary broadcast and digital standards.2 Consequently, Canadian dramas — prior to the proliferation of home video recorders — are ephemeral. They exist primarily in the recollections of those who watched them in real time. If you were to ask a Canadian teenager in the early 1980s to name a rerun, the response would likely be Fawlty Towers or M*A*S*H — reinforcing the postcolonial positioning that national broadcasting was designed to overcome.

Televisual heritage and nostalgia, in the Canadian context, thus become more individualized and generationally specific than their British and American counterparts. As Kompare’s work underlines, American children have continual access to the television cultures of their parents and grandparents in a manner that destabilizes the idea of “heritage” as a canon and reconstructs it as: “a part of the lived, historical experience of a culture. It becomes a critical resource, blurring the concepts of history and memory and forging national and cultural identities” (p. 103). It is the capacity of televisual nostalgia to operate as a “critical resource,” that I find most intriguing. Roberts’ earlier column aptly demonstrates how reruns (and the BBC’s role as arbiter of the national culture) can contribute to a regressive form of nostalgic longing for a ‘simpler time.’ Citing Gilroy’s depiction of “post-imperial melancholia,” Roberts hits the mark in that televisual retrospectives can elide the complexities of the politics of race and class. Yet it can also be argued that the very juxtaposition of vintage television with programs such as Ali G. and The Kumars at No. 42 offer the opportunity for ideological critique of both an imaginary mono-cultural past as well as the question of televisual authority/authorship itself. The past can also bring the present into stark relief and provide an opportunity for in depth political and social dialogue.

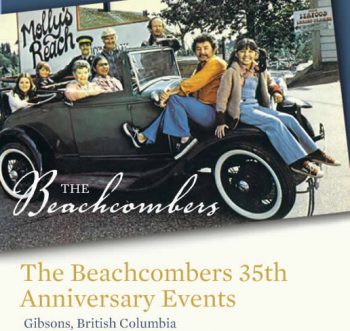

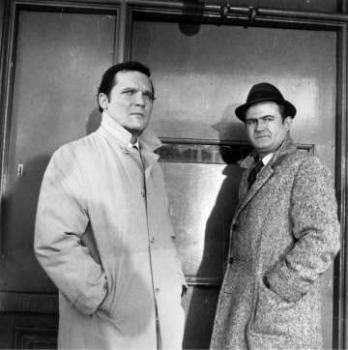

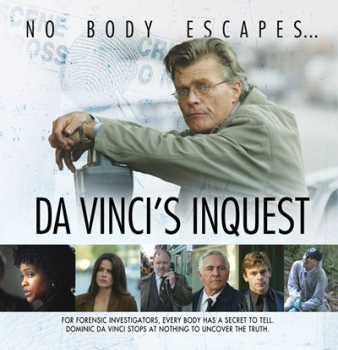

Canadian television, in contrast, provides a sense of existing in a perpetual present. Here, the past is indeed “a foreign country.” The lack of reruns is also a point of rupture that has impeded a sense of television heritage and, more importantly, prevented glimpses of the past (as retold by TV) that might foster understanding of the political and social struggles that continue to this day. An illustrative comparison here is between Wojeck (CBC 1966-8) and Da Vinci’s Inquest (CBC 1998-2005). Wojeck was a crime procedural based on the real-life cases of Toronto’s chief coroner Dr. Morton Schulman, and is often cited as the standard bearer for the social justice tone and dramatic realism that are seen as hallmarks of domestic drama. Wojeck pulled no punches in confronting issues of urban conflict, sexuality, and the drug trade. Thirty years later, Dominic Da Vinci (also based on a “real”chief coroner, Vancouver’s Larry Campbell) arrived on Canadian television screens to speak for the marginalized and crusade against precisely the same issues of structural inequality, poverty, prostitution, and drug addiction. To the best of my knowledge, Wojeck has only been rerun once in the past 10-15 years. If we were to imagine these two series as circulating simultaneously we can see the continuity of a specific television aesthetic as well as an indictment of a society that has not learned the lessons of history. Reruns are not necessarily sentimental journeys to an idyllic past. Our evaluation of the relationship between nostalgia and televisual heritage may also be a normative. For example, the current on-line petition to bring Canada’s longest-running drama series, The Beachcombers (CBC 1972-1990) back in reruns and DVD format indicates that many audiences indeed desire a return to a simpler time and place where the quirky characters of Gibson’s Landing defined British Columbia’s Sunshine Coast. However, the nostalgia for the small coastal community of the series’ story world includes an affinity for discourses that naturalized multicultural harmony, respect for native cultures, and a commitment to environmental issues (long before climate change hit the headlines). In a non-preachy narrative style, the series projected a preferred reading of progressive politics for generations of Canadians.

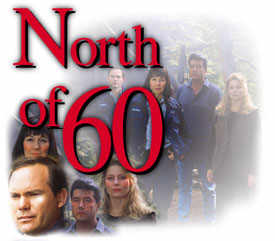

The proliferation of delivery windows and increased demand for content may provide an opportunity to revisit Canada’s television heritage. As Kompare notes, “boutique television” for niche audiences has established rerun cable stations par excellence (TV Land, Nick At Nite). In this regard, Canadian content regulations have somewhat resurrected the domestic rerun. Audiences of Dejaview and TV Land Canada may, by happenstance, stumble across Night Heat or North of 60 in between episodes of Love American Style or Facts of Life. But something may be lost as much as gained. For example, the fictional world of Lynx River, NWT in North of 60 introduced the Dene Nation to an avid national audience on the CBC (1992-7). In a boutique TV world, audiences must know about and be motivated enough to go out of their way to find reruns of the series. And it may only be shown there for a matter of months.

In the end, this column may be guilty of nostalgia too. Nostalgia for a time when broadcast television might have been a “cultural forum”3 where stories of people of different cultures, communities, generations, and interests encountered one another and, through the rerun, continued a dialogue across time. Two final musings as I run out of virtual space. First, I often wonder if the Degrassi franchise receives so much public and academic attention because it has not been ‘off’ Canadian TV, in one form or another, for more than twenty years. It carries several generations of cultural memory and may now actually be Canada’s television heritage. Second, I realize that my subtitle is something of a misnomer. Amnesia means forgetting something you experienced. In a no-rerun nation, you can’t forget what you never knew.

1. The Beachcombers

2. Wojeck

3. Da Vinci’s Inquest

4. North of 60

Please feel free to comment.

- Kompare, Derek, 2005. Rerun Nation: How Repeats Invented American TelevisionRoutledge. [↩]

- Binning, Cheryl, 2001. Film Past and Future: Preserving Canada’s Cinematic Heritage. Take One, March 21 [↩]

- Newcomb, Horace and Paul M. Hirsch, 1983. “Television as a Cultural Forum,” Quarterly Review of Film Studies [↩]

Serra,

Once again, an excellent, thought-provoking column. Which brings up the following, free-floating set of thoughts.

When I was very young, one thing that struck me as an Ontario-resident receiving broadcasts from Buffalo, NY was that Canadian TV seemed very much to be a ‘bad object,’ or at the very least, obviously inferior. I would almost go as far as to say that due to my consumption of almost exclusively American TV, I didn’t know that there was a big difference between Canada and the US for the first couple of years. No one I knew willingly or knowingly watched Canadian programming (including De Grassi) and when we did, it was accidental. Only now, do the adults I know admit that they watched these programs with any pride.

I wonder if the Canadian content regulations have something to do with the ephemeral nature of Canadian TV, in that many of these shows (even successful ones) are cancelled soon after the Canadian tax credits run out. I also wonder about the persistance (and perhaps international presence) of The Anne of Green Gables, Road to Avonlea (etc…) as a cultural export as I recall that show playing for about 10 years in syndication (4 pm, after school).

Finally, I find it odd that I can watch many more CBC programs (like Da Vinci, Being Erica, The Border) on my US premium cable delivery, which play back to back to back episodes…

Thanks again for such satisfying and provocative reading.

Colin

Intriguing look at the national variations of rerun culture. You’re absolutely right about the particularities of the Canadian television market as the major factor limiting reruns of Canadian TV. The realization of the profits derived from reruns were the only thing that sparked their development in the US at all. As I wrote in RN, they had to be conceptually created, and industrial skeptics won over, over several years in the 1950s, before they became normative.

Your big cultural question–what role(s) do reruns play in national memory?–is tricky to answer everywhere, but particularly in their virtual absence. The role reruns play constantly changes as access to and interest in old TV shifts over time (as markets, technologies, ideologies, and other media forms develop). I’m thinking that we’ll always have access to “old TV shows” in some form, but a broad “rerun culture” may vanish as part of American identity as we’re no longer watching the same three channels anyway. As you point out, this situation is extremely exacerbated in Canada, where you really have to actively seek out *Canadian* TV, if it’s even available. Thus, Canadian cultural memory is much less likely to derive from Canadian TV (relative to, in your analysis, the UK and US).

Finally, as an American who has lived far from the Canadian border, my primary memories of Canadian TV culture come from sketch comedy: SCTV and the Kids in the Hall (I’ve never seen Degrassi). What’s interesting with each of these is how, although they primarily function in a broad “North American” vein (from their times, the 1980s and 1990s, respectively), they do also draw on Canadian-specific references on occasion. For example, my Canadian sister-in-law (from Vancouver) had to explain to me the specifics of a few KITH sketches (regional dialect, place names, etc.). In those moments, its function (in US rerun culture) becomes a bit more like UK TV comedy; i.e., as something familiar yet somehow “alien.” A sad commentary on the prominence of Canadian culture as seen on US media, but there it is!

Nice job, great question, and interesting discussion.

To add to the aspects of this phenomenon, such as industry reluctance to believe that showing something “old” would attract viewers and the popular perception of Canadian programming as something inferior foisted on the audience by the CBC, let me offer further ruminations that might suggest ways to extend your own. The cultural “amnesia” and narrative of absence you attribute to the lack of reruns can depend on your (my) age, ability to remember, availability of competing diversions, and the integrated (or not) media/social environment. My own research encourages Canadians to examine culture with regard to what is there in concert with what is not there, rather than focusing on absence.

If I look at the 1950s and 1960s for example, I can se that what NBC called “appointment television” served some of the “generational memory” you attribute to reruns. When I was little in Ottawa, the CBC provided use programming on one English station and one French station–I think they went on the air about noon — and circa 1959 an English CTV station went on the air at about 4 p.m. These are memories I can check against the facts, of course. But the upshot is that we couldn’t submit ourselves to a lot of competing media messages, even if our mothers would let us. Still, weekly served me the way that reruns might serve others, characters developed in ways a little different thatn dramatic torylines, but still worthy: Don Messer’s Jubilee, Juliette, the Littlest Hobo, television specials (or even Ed Sullivan appearances) by Paula Anka, Rich Little and Wayne & Shuster, Chez Helene and The Friendly Giant –Yes I watched them in real time, but I don’t need reruns to remember images, messages, even script snippets from them (“and one big chair for two to curl up in”), even at my age. I guess you can kinda tell how old I am — creak, creak. But memories, even the television memories, of my generation are worth mining rather than discounting in the continuing project of (after Carey 1992) constructing, maintaining and transforming Canadian national identity — and would make for fantastic class research projects, if I do say so myself.

Many NFB films served a “rerun function” on one level, if someone required rerun nostalgia to produce a patriotic feeling or want to interpret the past through the present. Students especially could watch certain movies more than once, and often did depending on school, grade level and availability from the public library. And some were rerun on television, especially the minute-long historical vignettes. In the broader media landscape, Canadian Content regulations (gasp) in radio emerged requiring that we hear more Neil Young and Bryan Adams and Lighthouse and the Guess Who in the 1970s and 80s — many of us are the better for much of that, actually. At the same time, few of the people I knew (teens and twenties at the time) would touch The Beachcombers (dare I say ANY Canadian drama?) with a 10-foot branch of Douglas fir. In fact, the program was incorporating messages that were integrated across the social landscape in both media and other ways: David Suzuki was emphasizing the same environmental messages on The Nature of Things, in the news the Mackenzie Pipeline Hearings were foregrounding issues specific to the environment and First Nations peoples, the government’s Multicultural messages were integrated across the social landscape in many policies and programs. (That this program delights people now encourages me to take another look, although I don’t know if it will be as popular around my house as Corner Gas — OK, OK, so we became fans of the situation comedy Corner Gas down here in the States when it was rerun on an American station.)

Looking at the issue from the perspective of the absence of a social artifact or process from which other societies benefit suggests certain conclusions, but looking at it from the perspective of the integrated social presence of messages and their accumulated influence allows insights that can offer a critic or researcher even more.

By the way, that Wojeck/Da Vinci’s Inquest analysis sounds like a great idea.

Thank you Serra for the excellent column.

The issues that you have raised speak to many of the challenges that I am currently facing as a young scholar of Canadian television. Specifically, how might I familiarize myself with a broadcasting history that I have for the most part not experienced and which has, outside of work on policy, received relatively little academic attention (though this has started to change in recent years).

While I acknowledge that accessing productions via the CBC (as either an academic or an audience member) poses certain challenges, I think a more pressing concern is, how we might access such materials if the institution of the CBC should continue to dissolve? Even now, many of the shows that I study are not maintained in the CBC’s video library. This is because, despite being involved in their production, the CBC has not been able to negotiate re-broadcast rights. As such, there is not much reason to keep copies of these shows around and collecting dust. Increasingly, popular CBC shows are being produced by other companies off-site. With the transition from production to mere broadcasting, the CBC will lose, in my opinion, an important stake in Canadian media. As challenging as it may be to find points of entry into the content history of the CBC, the job of the researcher will only become more difficult as production is decentralized and complete audio, video, and production archives cease to be maintained.

Hi there,

I am a Canadian film student on exchange to study my MFA at the USC School of Cinematic Arts. I am in a class devoted to television studies. The majority of programming featured in the class, if not all, is American.

My focus within the Television and Film industry is children’s media and entertainment. It is within this framework that I approach your article.

While I have a hard time remembering any ‘adult’ series reruns on TV, my memory and nostalgia of TV watching as a child reveals a large amount of Canadian programming.

One of my favourite discussions to have with people is about Kids TV and what we watched growing up. Here in the US most people have no idea what I am talking about when I mention programs I was addicted to as a kid. This is fascinating to me as I never realized how many Canadian kids shows I watched. Mr. Dress-up, for example, was not popular in America, while I grew up watching the American Mister Rogers as well as the Canadian Mr. Dress up.

When thinking about Canadian kids programing I can recall a majority of programing being “old” and from “my parent’s time.” For example, Mr. Dress-up (1967 to 1996) and The Friendly Giant (1958 -1985), both of which aired when my mom was a kid.

I have a little brother who is nine years younger than me, so I grew up with essentially two generations of Kids TV. While a ‘first run’ for me in the 1990s, shows like Are you afraid of the dark, Babar, Breaker high, Caillou, and The Elephant show (Sharon, Lois and Bram), Reboot, Big Comfy Couch, Freaky Stories, Student Bodies, Stickin Around, The busy world of Richard Scarry, were all aired as ‘reruns’ to his generation. In fact, some of these shows are still on today.

People are always nostalgic for their childhood. Childhood is powerful stuff. Combine this with Canadian children’s television and I wonder how this impacts this argument. Could the memory of children’s Canadian TV replace the void for missing reruns of Canadian TV?

I would be very interested in hearing your thoughts!

Thank you,

Paisley