This Was England: British Television And/As Cultural Heritage

Martin Roberts / The New School

I don’t watch much British television these days, if by that you mean programming available—officially, at least—exclusively within the territorial UK. Having lived in the US for several decades, I’ve long since tired of BBC America’s incongruous diet of Cash in the Attic re-runs, freak-show documentaries (“My Fake Baby,” “My Mums Used To Be Men,” “Britain’s Worst Teeth”), soft porn soaps (Footballer$ Wives, Mistresses), Top Gear marathons, theme nights (“Supernatural Saturday”), and Gordon f***ing Ramsay. British television networks restrict online access to domestic programming to license-paying UK residents, and while there are workarounds, expatriates wishing to access it have limited options compared to, say, their Japanese or Korean counterparts. Most of the British television I’ve watched in recent years has been either on DVD or obtained from online torrent communities, whose expanding archives still offer only a sampling of the rich national mediascape available to domestic viewers.

All of which is why, whenever I visit the UK every year or so, as I did during the recent holiday, I’m always struck by how different the British television that people in Britain itself are watching is from the rarefied version of it available to expatriate viewers like me. What struck me in particular this time was its pervasive nostalgia, a longing for the nation itself as it once was or is imagined to have been. This was no doubt in part seasonal—Christmas is, after all, a festival predicated on nostalgia—yet still seemed excessive even by usual standards. Nostalgia is hardly new to British television, of course: sitcoms such as Dad’s Army, It Ain’t Half Hot Mum, and ’Allo ’Allo have been poking fun at the nation’s wartime and imperial past for decades, while satellite networks maintain a steady stream of “classic” programming. But nostalgia has today become one of the dominant modes of what the British sociologist Michael Billig (2005) calls “banal nationalism,” the everyday social rituals and discursive practices by which national identity is routinely reaffirmed, and British television plays a key role in this process.1 Consider its fascination with the national rail system: in the space of several weeks, I watched three documentaries about the Age of Steam and the “romance” of train travel in fiction and film (in stark contrast, it may be added, to the calamitous state of the contemporary rail network). The BBC’s holiday schedule included a re-run of one of its (four) adaptations of Edith Nesbit’s book The Railway Children (1968) and of Charles Dickens’ ghost story The Signalman (1976).

[youtube]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Qf0jcGb0_qQ&feature=related[/youtube]

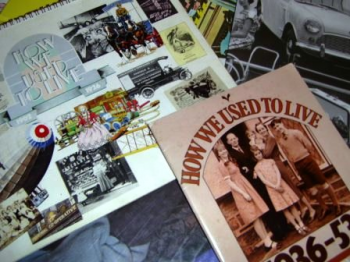

Yorkshire Television’s educational drama series How We Used To Live has been broadcast since the 70s, and its shows have themselves become a site of nostalgia, posted on YouTube and torrent sites by fans reminiscing about their childhood experiences watching it.

[youtube]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9RPJpo65Js0[/youtube]

Recent years have seen a growing number of similar series with titles like The Way We Were (ITV), Nation on Film (BBC) and Those Were The Days (ITV) which draw heavily on home movies and footage from local film archives.

British television’s most intense nostalgia, however, is reserved for itself: much of the BBC’s schedule consisted of “classic” Christmas specials I had watched in the 1970s: Morecambe and Wise, The Two Ronnies, Top of the Pops. An hour-long documentary was devoted to the long-running children’s show Blue Peter. This self-reflexivity reaches its height in one of the nation’s best-loved institutions, Doctor Who, which functions almost as a compendium of its own forty-five year history, reincorporating Daleks and Cybermen with contemporary cultural references and celebrity cameos. Watching domestic television today, one can easily feel like the time-travelling doctor himself, stuck in a televisual time-warp continuously looping between the 60s and the 80s.

In her book The Future of Nostalgia, the Russian cultural theorist Svetlana Boym observes that although at first glance nostalgia is a longing for a place, “it is actually a yearning for a different time—the time of our childhood, the slower rhythms of our dreams. . . . The nostalgic desires to obliterate history and turn it into a private or collective mythology, to revisit time like space, refusing to surrender to the irreversibility of time that plagues the human condition.”2 British television offers a compelling case study in nostalgia and the medium’s role in converting private memories into a shared cultural mythology. It is no coincidence that so much of the historical programming it offers takes the form of children’s shows: like an electronic toy-box filled with a hodge-podge of half-forgotten artifacts, it invites viewers to relive their own childhood vicariously through it. Much of the nostalgia of contemporary shows is what Boym calls “restorative,” explicitly aimed at turning back the clock to a historical time-zone in some cases predating modernity itself, most clearly on view in the self-conscious pastoralism of celebrity chef-turned-gentleman farmer Hugh Fearnley-Whittingstall.3

[youtube]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ymUVooxHjIk[/youtube]

The concept of “heritage” is often associated with the costume dramas of 1980s British cinema, but cinema itself is only part of the larger heritage industry in which television is also a major participant.4 From its inception, the BBC has positioned itself as the custodian of the nation’s collective memory, a role it continues to play through documentary series on the national landscape (Coast, Wainwright’s Walks) or social history (the Britannia series on popular music). Yet both the BBC and the ITV franchises today clearly see themselves as an indispensable part of that heritage, and have for some time been engaged in the painstaking project of reconstructing their own past, not just via re-runs and DVD releases, but also documentary “tribute” shows (All About Thunderbirds, The Old Grey Whistle Test Story), or behind-the-scenes biographies of “classic” TV personalities (Hughie Green, Ronnie Corbett). British television today is primarily a commemorative medium, looking wistfully back on its own childhood as well as that of its audience, conjuring up a national community which may have little common ground anymore other than having grown up watching the same shows.

Paul Gilroy (2004) has diagnosed the current condition of British society as one of “post-imperial melancholia,” a morbid attachment to the nation’s imperial past and a grudging conviviality with the generation of immigrants whose arrival since the 1950s has transformed traditional understandings of national identity.5 Rather than melancholia, however, it is arguably nostalgia which is the current British affliction, “a longing for a home which no longer exists or never existed”6, a home of steam trains puffing through the English countryside, of seaside amusement parks and cockles on the pier, of country pubs and clotted-cream fudge, of Kenneth Williams and Steptoe and Son—a home before the Notting Hill carnival, before Stephen Lawrence and Satpal Ram, 9/11 and 7/7, Ali G and The Kumars at No. 42. It is a world which today survives largely in the memories of our grandparents, yet still maintains a surprising visibility in British popular culture thanks to the memory-machine of television. Heritage television offers a reassuring shelter to an older generation from the less pleasant realities of the contemporary nation documented in other media, such as Shane Meadows’s depiction of British skinheads in This Is England (2006), or the paranoia over Muslim fundamentalism dramatized in Channel 4’s docudrama Britz (2007).

Ultimately, British television’s nostalgia for itself may be seen as a reaction to its own inexorable demise, as digital and broadband technologies threaten to render obsolete the very concept of “television” itself and the medium is increasingly overtaken by gaming as the dominant form of popular entertainment. In the face of such challenges, Britain’s heritage television is in every sense, as Marilyn Ivy (1995) has put it in a different context, a discourse of the vanishing. 7

Image Credits:

1. How We Used to Live?

2. Commemorating the Styles of Yesteryear

Please feel free to comment.

- Billig, Michael. Banal Nationalism. (London: Sage Books), 1995 [↩]

- Boym, Svetlana. The Future of Nostalgia. (New York: Basic Books), 2001, xv [↩]

- Ibid., xvii [↩]

- Vincendau, Ginette. Film/Literature/Heritage: A Sight and Sound Reader. (London: BFI), 2001. [↩]

- Gilroy, Paul. After Empire: Melancholia or Convivial Culture? (New York: Routledge), 2004. [↩]

- Boym, xiii [↩]

- Ivy, Marilyn. of the Vanishing: Modernity, Phantasm, Japan. (Chicago: University of Chicago Press), 1995. [↩]

Nice piece, Martin–if you want to follow UK TV closely now, the option is there–you can get SlingPlayer to warehouse in Britain both a satellite dish and a SlingBox, which you can access from here on your computer and watch to your heart’s delight–+ no license fee!

very astute observations but it’s not just at chrsitmas it’s all the time. part of the explanation is in your conclusion about a dwindling audience of early middle age through to pensioner viewers and the younger market being taken over by gaming and facebook and the like. but i think it has always been like that and there is a danger of falling for the nostalgic ‘golden age’ that your argument diagnoses. what’s new is the enormous expansion of channels and sub-channels. that is driven by investment decisions about digitally driven distribution technologies, although perhaps now one can expect the ‘digital switchover’ to slow down, over investment in content prodcution. as something has to fill the time then just re-run what has already been made – although there is some enjoyment in a time when smoking was allowed and political correctness hadn’t been invented (Minder, On The Buses). that’s not to say that some brilliant new stuff isn’t being made, at least by british tv standards, especially comedy and factual, but not much more proportionate to the channels available and compared to the old days of only 2, 3 or 4 channels. and the new stuff gets strung out across all the channels, where an ideal bbc comedy hit begins on radio, then gets a television airing on digitial BBC 3, then to BBC2 and then BBC1 where it is repeated 2 or 3 times in one year. Channel 4 has a similar model. that may be because there simply isn’t enough ‘talent’ out there and what there is finds its way to television through the tried and trusted way of luck and cunning. anyway from what i can tell it’s pretty similar in the states. i mean, what is that thing with the talking horse all about? must go as they’re showing Aguirre, the Wrath of God on BBC 4.

Great Article! I wonder if Gilroy’s conception of “post-imperial melancholia” could be usefully combined with Svetlana’s understanding of nostalgia — maybe a “post-imperial nostalgia”? The two positions don’t seem mutually exclusive, given an understanding of the ideological content of specific BBC television programs, a view buttressed by your understanding of “heritage” in contemporary British television.

Hi, I’ve read your column several times now – wanting to disagree with it, but finding in many ways I can’t. In reading through your list of nostalgia driven TV I don’t know whether you are aware that there was actually a specific series of dramas shown on BBC4 here which visit (as a sort of costume/bio) figures from British television – and they are (you guessed it) Kenneth Williams, Tony Hancock and Steptoe and Son, this series also includes the one on Hughie Greene (is this the one you mention?) but it is a very different kind of programme to a gentle behind the scenes (with the still living) Ronnie Corbett. One of the few women to get a look in is Fanny Craddock. Each drama provides an opportunity for the channel to ‘theme’ an evening etc etc.

Anyway I’m still thinking – is it really nostalgia? Some of the shows I mentioned were quite brutal character studies revelling but also revealing about the hypocrisy of the time – but may be that’s your point, from the present the past can be comfortably repackaged and critiqued.

hmmm maybe I’m simply the target audience for this kind of thing – after all I remember How we Used to Live from school.

Thanks to all for the responses so far.

@Toby: I know about Slingbox but haven’t tried it. Not sure what you mean by warehouse but I wasn’t aware that Sling would host a satellite dish + Slingbox setup. Other than that, the best bet seems to be IP spoofing, which has sparked a good deal of entrepreneurial activity of late and is now available as a subscription service from certain… companies. Seems like a good idea but since fake IPs don’t usually last long before getting either immobilized by traffic or blocked, whether it’s a viable business idea remains to be seen.

@Jeremy: my point in a nutshell is that what I call heritage TV and today’s multicultural TV are in many ways two sides of the same coin, and I certainly agree that they’re addressed to audiences of very different generations. Which raises the question of how long heritage TV will continue, or whether it is a vanishing discourse – once the Grumpy Old Men (and Women) have passed on, who will be left to watch it? Or perhaps today’s youth will be getting teary over classic old episodes of the Kumars and Ali G.

@Michael: in her book Svetlana Boym differentiates melancholia, which she sees as pertaining to individual psychology, from nostalgia, which is more of a social phenomenon, (what Arjun Appadurai calls a “community of sentiment”). This seems reasonable to me and is why I’m sceptical about Gilroy’s term, although of course psychological models are frequently and unproblematically applied to large social collectivities – the national “psyche” being a case in point.

@Karen: you raise a valid point about the fact that the docs about elderly or now deceased celebrities, which often foreground the disparity between the TV persona and the “real” person behind the scenes, can be considered as “nostalgia.” Inasmuch as such docs typically include numerous clips from the original shows the celebs were in, though, they arguably function the same way. That said, by nostalgia I’m not thinking of it in an exclusively rosy, those-were-the-days sense. Much of the nostalgia one sees on UK TV is about hardship, especially when WW2 is involved (rationing, bombing raids), but it’s the shared nature of the experience which provides the sense of community, then and now. Perhaps it’s this sense of (imagined) community which is the ultimate object of nostalgia, again in contrast to the fragmentation of it in the postmodern/postcolonial world. In this sense it’s interesting that so many of the most fetishized objects of nostalgia in UK media are about community – The Archers, Emmerdale, etc.

Hi Martin–Echostar (which owns the Slingbox company) will keep a satellite dish and a slingbox for you in the UK which you can use to watch UK TV of all kinds, live and legally, from anywhere in the world on any computer which has the right software (a free download) and which you have given the key codes to that articulate directly both to your dish and your Slingbox. It works the same as having a Slingbox in the US next to your satellite or cable box for US content, except you’re not in the same country as your dish or Slingbox

I really enjoyed reading this piece, too… something similar is going on in former Yugoslav countries as well – after the 1990s wars, the media are being mobilized in seven (!) new nation states (Slovenia, Croatia, Bosnia&Herzegovina, Serbia, Montenegro, Macedonia, Kosovo) in an attempt to re-create a shared Yugoslav cultural memory. Discourses of nostalgia for the former Yugoslavia circulate in a variety of media texts – including tv shows – romanticing the Yugoslav time/space before the wars, when “we were all so happy”…”before we started to kill each other”…

Perhaps Yugo-nostalgia might be characterized as “imperial” in the sense invoked by the anthropologist Renato Rosaldo: “in any of its versions, imperialist nostalgia uses a pose of ‘innocent yearning’ both to capture people and imagination and to conceal its complicity with often brutal domination” (1989, p. 70). Rosaldo argues that imperial nostalgia looks back at something that it helped to destroy and mourns this loss, as in the case, for example, of British portrayals of Indian culture (in, for example, Merchant Ivory films). Yugo-nostalgia, as imperialist nostalgia, revolves around a paradox: a person kills somebody, writes Rosaldo (1989), and then mourns his or her victim… It is as if the Yugoslavs had to destroy their country in order to truly appreciate its possibilities by confronting the prospect of living without them. And we see Yugo-nostalgic practices on the rise…

Rosaldo, R. (1989). Imperialist Nostalgia. Representations 26 (2), 107-22.

In brief, it’s surprising to me that no one has mentioned BBC’s Life on Mars yet, which is the embodiment of this nostalgia by way of time-travel and even goes as far as to adopt the form of certain BBC cop-shows as I understand it.

It’s interesting how different nation states fixate on certain periods–the Victorian era in England and a combo of the “wild west” and the 1950s in the USA–suggesting this type of national nostalgia is very much fixed on moments of expanding empire or international dominance.

Still, even give the “post-imperial melancholy” of the BBC these days, they still seem to find some space to put that heritage in rather arch quotation marks. I remember a week in the early ’90s when the BBC re-purposed all of their most horrible productions for “The Worst of the BBC” (including an incredibly stagebound video adaptation of H.G. Well’s “Outline of History”). “Look Around You” (currently on Adult Swim) takes a similar look at the halcyon days of educational tv/new tech mania in the 70s.

Maybe, as some have suggested, (melo)drama is an inherently conservative and frequently nostalgic genre–and as most melodrama still basically proceeds from the foundations of 19th century British fiction, these tendencies become highly overdetermined in BBC dramas. It strikes me that in general “dramatic” programming has gradually lost its place to comedy as the preeminent “political” genre in television (no missives about “The Wire” please), precisely because so much of the new comedy ridicules the false social cohesion/cultural stability/historical consensus inherent in much dramatic programming.

Pingback: No Rerun Nation: Canadian Television and Cultural Amnesia Serra Tinic/ University of Alberta | Flow