A Tear for Sarah Jane – A Feminist Aca-Obit

Hannah Hamad / Massey University

I had something entirely different planned for this column. However, the sad news on April 19th of the death of the British actor Elisabeth Sladen, who played Sarah Jane Smith, the most iconic of Doctor Who companions, prompted me to abandon it to take this opportunity to pay tribute to Sarah Jane’s adventures in feminism and postfeminism.

Sladen originated the role of the young investigative journalist in classic Doctor Who (1973-1976), reprised it in the abortive spin-off K9 & Company (1981), made occasional appearances as Sarah in the new Doctor Who (2006-2010), and was the eponymous heroine across four seasons (a fifth was midway through production when Sladen fell ill) of The Sarah Jane Adventures (SJA, 2007-2010), marking an extraordinary career renaissance for her, aged fifty-nine.

Doctor Who, and cult sci-fi more broadly, is not generally known for the feminist scholarship it has generated, due in part to its being a favoured object of eminent aca-fans who naturally bring to bear on it their preferred modes of analysis. Nonetheless, in the small but growing body of work on gender in Doctor Who1, discussions frequently turn to Sarah, who in her original incarnation was the series’ poster girl for second wave feminism; a notable development given the troubling gender politics for which the classic series is known2, and in contrast to which “Sarah [was] often taken to mark a new era for the programme in its search for more positive female roles.”3

Her predecessor, Jo, was a mini-skirted dimwit who failed A-level science, while the actor who played her (Katy Manning) famously posed nude with a dalek for a top-shelf magazine in 19774, a formative year in the feminist anti-pornography movement5. Her successor, Leela, was a “leather-loin-clothed cave girl… brought in for dads”6 and to allow the Doctor to effect and enact upon her a Pygmalion-esque makeover to contain her knife-wielding unruly femininity. Her feisty action-heroine credentials notwithstanding, Leela was hardly an example of the “prime time feminism” that Bonnie Dow argues attempted to negotiate the changing social discourses around gender in the 1970s.7 But Sarah was. She was conceived and introduced in direct response to these changes, and she has repeatedly been the benchmark for the series’ negotiation of “both entrenched and shifting gender norms.”8

Her nominal feminism is most pronounced in her inaugural story ‘The Time Warrior.’ Her introduction to a condescendingly paternalistic Doctor is marked by her tart refusal to make his coffee, and her optimistic attempt at feminist consciousness-raising in a thirteenth-century England scullery, while undercover as a kitchen wench: “I’m not afraid of men. They don’t own the world. Why should women always have to cook and carry for them?” She later dismisses the false consciousness evinced by women there as “subservient poppycock.” Three stories later in ‘The Monster of Peladon,’ Sarah’s feminism is briefly revisited as she lectures the biddable ingénue Queen of Peladon on the virtues of “women’s lib,” assuring her that “On earth… we women don’t let men push us around,” and that “There’s nothing “only” about being a girl.”

That was more or less it for Sarah’s feminist posturing, which in retrospect seems gimmicky, tokenistic, and fleeting, soon giving way to familiar cultural scripts for the containment of feminine agency. While her real world counterparts in the activist group of female media professionals Women in Media marched on Parliament,9 Sarah was Fay Wray to a robotic King Kong in ‘Robot,’ was tied to a rock and tortured in ‘The Sontaran Experiment,’ blinded in ‘The Brain of Morbius,’ served up as a human sacrifice in ‘The Masque of Mandragora,’ and possessed in ‘The Hand of Fear,’ all in a standard cycle of scream, jeopardy and rescue.

Nonetheless, Sarah struck a chord with audiences. She was the “best loved”10 of the Doctor’s companions. This, I like to think, was due in part to her headstrong personality, self-possession, wit, inquisitiveness, and unruliness, which appeared at times to transcend the limitations of her agency and the flimsy tokenism of the more seemingly deliberate trappings of feminism attached to her character, such as her “‘tomboyish’ clothes [that] were designed in accordance with the dominant media representations of feminists,”11 and her upwardly mobile profession as a journalist.

In 2006, Sarah was reunited with the Doctor thirty years after he disappeared from her life in ‘School Reunion,’ a postfeminist cautionary tale of the abject singlehood12 that awaits the Doctor’s discarded companions. It also sowed the seeds of the postfeminist gender discourse that would subsequently characterise SJA through its depiction of generational disharmony and toxic sisterhood evinced in the fractious exchanges between Sarah and Rose, an upshot of producer Russell T. Davies’ instruction to writer Toby Whithouse to “write it like Sex and the City.”13

[youtube]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3fq17ZSY-II[/youtube]

Commensurate with the pointedly postfeminist manner in which the character was re-imagined for the twenty-first century, the potentially troubling scenario of her having aged into abject singlehood was deftly discursively surmounted in a number of ways, both textual and paratextual, as she was positioned as what Sadie Wearing calls a “subject of rejuvenation”14 (see example illustrated below), and thus her potentially problematic ageing femininity was “managed,”15 facilitating a culturally apposite re-entry into postfeminist culture.

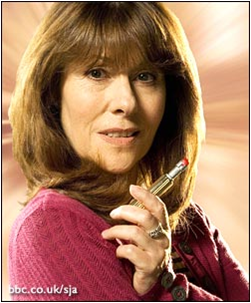

SJA has consistently been a ratings winner on BBC TV’s children’s channel CBBC.16 Despite its seeming celebration of mature feminine agency, it nonetheless articulates some worrisome postfeminist tendencies. The tone was set when the extraordinary scenario whereby the heroine of a children’s sci-fi action-adventure series was a childless single woman approaching her sixties proved to be predictably short lived, as by the conclusion of inaugural episode ‘Invasion of the Bane’ Sarah fortuitously acquires a fourteen-year-old son. There is also the matter of the patently troubling connotations of Sarah’s catchphrase “Mr Smith, I need you,” which activates her supercomputer, a masculinised voice of intellectual superiority and authority, while in ‘Whatever Happened To Sarah Jane’ Sarah’s best friend from childhood (Jane Asher) shows herself to be duplicitous and murderous in one of many depicted instances of toxic sisterhood and monstrous femininity. Other featured female archetypes and tropes range from the madwoman in the attic, to the runaway bride, but most iconic of all of the over-determined signifiers of postfeminist femininity in SJA is Sarah’s sonic lipstick, which is deployed time and again as a visual shorthand for her empowered femininity.

My ambivalence about the show’s postfeminist gender discourse notwithstanding, I thought SJA was extraordinary for its discursive centralization of a sixty-something single woman with agency and amiability. I shall miss her.

Image Credits:

1.Doctor Who, ‘Planet of Evil’ tx. 27 Sept 1975 – 18 Oct 1975: author screen grab.

2.Doctor Who, ‘The Time Warrior’ tx. 15 Dec 1973 – 05 Jan 1974”

3.The Daily Record, 13 October 2009, p 27: author scan.

4.The Sarah Jane Adventures publicity still:

Please feel free to comment.

- Dee Amy-Chinn, ‘Rose Tyler: The Ethics of Care and the Limits of Agency’ Science Fiction Film and Television. Vol. 1, No. 2 (2008), pp 231-247; Richard Wallace,‘“But Doctor? – A Feminist Perspective of Doctor Who’, Lee Barron, ‘Intergalactic Girl Power: The Gender Politics of Companionship in 21st Century Doctor Who’ in Christopher J. Hansen (ed), Ruminations, Peregrinations, and Regenerations: A Critical Approach to Doctor Who (Newcastle-Upon-Tyne: C-S-P, 2010), pp 102-116, 150-162; Piers Britton, ‘‘WHO DA MAN?’: The Doctor’s Masculinities’ and ‘‘I’M NOT HIS ASSISTANT!: Being The Companion’ in TARDISbound: Navigating the Universes of Doctor Who (London: IB Tauris, 2011), pp. 83-145. [↩]

- James Chapman, Inside the Tardis – The Worlds of Doctor Who: A Cultural History (London: IB Tauris, 2006), pp 6, 79; Britton, p 124. [↩]

- John Tulloch and Manuel Alvarado, Doctor Who: The Unfolding Text (London: Macmillan, 1983), p 212. [↩]

- Tym Manley ‘Kissing The Daleks Goodbye’ Girl Illustrated (1977) Vol. 8, No. 10. [↩]

- Lynne Segal, ‘False Promises – Anti-Pornography Feminism’ in Mary Evans (ed), The Woman Question (2nd Edn) (London: Sage, 1994), p 356. [↩]

- Jack Bell, ‘Daddy’s Girl…’ The Daily Mirror (31st December 1976), p 15. [↩]

- Bonnie J. Dow, Prime-Time Feminism: Television, Media Culture, and the Women’s Movement Since 1970 (Philadelphia: Pennsylvania UP, 1996). [↩]

- Britton, p 112. [↩]

- Dale Spender, There’s Always Been a Women’s Movement This Century (London: Pandora, 1983), p 126. [↩]

- Britton, p 124. [↩]

- Tulloch and Alvarado, p 102. [↩]

- Diane Negra, What a Girl Wants? Fantasizing the Reclamation of Self in Postfeminism. (London: Routledge, 2009), p 61. [↩]

- Doctor Who Confidential, ‘Friends Reunited’ tx. BBC3, 29th April 2006. [↩]

- Sadie Wearing, ‘Subjects of Rejuvenation: Aging in Postfeminist Culture’ in Yvonne Tasker and Diane Negra (eds), Interrogating Postfeminism: Gender and the Politics of Popular Culture (Durham: Duke UP, 2007). [↩]

- Negra, p 77. [↩]

- http://www.barb.co.uk/report/weeklyTopProgrammes. [↩]

Pingback: Daily News » Blog Archive » Aca

Pingback: Latest News » Blog Archive » Aca

Pingback: Little News » Blog Archive » Aca

Pingback: DAILYNEWSONLINE.INFO » A Tear for Sarah Jane – A Feminist Aca-Obit Hannah Hamad / Massey …