24: Jumping the Shark Every Minute

The following is a somewhat revised version of the afterword to Reading 24: TV Against the Clock, edited by Steven Peacock (forthcoming from I. B. Tauris).1

“When all the archetypes burst out shamelessly, we plumb Homeric profundity. Two clichés make us laugh but a hundred clichés move us because we sense dimly that the clichés are talking among themselves, celebrating a reunion.”

— Umberto Eco, “Casablanca: Cult Movies and Intertextual Collage”

This month, most network television shows, new and returning, will begin their seasons. The most timely of all series, however, Fox’s 24, won’t be back until January. For the third year in a row, 24 will not return until the new year, giving Joel Surnow and Robert Cochran and the other makers of the hit terrordrama’s sixth season time to have enough episodes in the can for unbroken weekly airing, January to May, of an entire day in the life of Jack Bauer.

Day 5 (Season Five) of 24 was better than ever. Commencing fourteen months after Day 4 (Season 4), 5 was a killer: Jack Bauer, as we knew though the world did not, was still alive, but former President Palmer was assassinated and Michele Dessler, Tony Almeda, Lynn McGill, Edgar Stiles, and score of nameless bit players would die. Secret Service Agent Aaron Pierce had emerged as perhaps the most interesting minor character in televison. Chloe scowled better than ever. POTUS Logan proved to be a more detestable wuss than on Day Four, morphing into a creepy hybrid of Richard Nixon and George W. Bush. FLOTUS Martha was irresistibly unhinged and wonderfully capable of testing her husband’s spineless mettle.

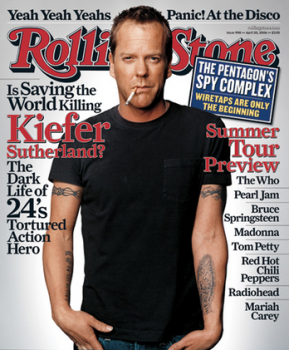

No doubt about it, 24 has become a cultural phenomenon. A big screen version is in the works for 2008. Kiefer Sutherland has re-upped for three more seasons and made the cover of the Rolling Stone. During last spring’s debate (inspired by the harsh criticism of several retired generals) over the status of Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld, a commentator was heard insisting that Rummy couldn’t care less — not being a deeply conflicted “Jack Bauer” type. (Had he ever watched the show? Jack Bauer conflicted? The CTU agent capable, in a LA minute, of decapitating a man, torturing his own ex, shooting an innocent wife in the leg–conflicted?). And in June the right’s Heritage Foundation staged a discussion of the series featuring members of the cast and real Homeland Security chief Michael Chertoff (Fessler).

I have watched every hour of 24, heard every nervous tick, from the beginning, and almost from the outset I have told anyone who cared to listen that I would probably never write about the series. A scholar-fan of such television programs as Buffy the Vampire Slayer, The Sopranos, Deadwood, Twin Peaks, The X-Files, and Lost, my strong preference has been for Quality television offering richly imaginative, genre-bending, abundantly intertextual teleuniverses with fascinating, inimitable characters and inspired writing. It’s not that I didn’t like 24 — indeed I loved it and still do, but as a guilty pleasure. As a lapsed English professor now immersed in television studies, I was especially enthralled by the capable-of-any-savagery Jack Bauer, who, I was shocked to learn in the Season One tie-in book, earned a B.A. in English at UCLA. But 24 itself, despite its English major hero, didn’t seem to call for a close reading.

In basic agreement with an observation in Steven Peacock’s collection on the series that 24 “both seems like quality television and the farthest thing from it,” I have felt no need to engage the series in any other way than as a fan. And yet other essays in Reading 24 offer remarkably ingenious and cogent discussions of such topics as 24‘s innovative use of split-screen in the context of the history of Western art; its political themes in light of its sponsors and the popularity of the SUV; women’s narrative authority in a very male story; the post Abu Ghraib ethics of its reliance on torture; and Chloe’s Asperger’s Syndrome.

Though I have watched 24 ardently, my suspension of disbelief for a series “often fantastic and excessive in spite of its appeals to realism” (as an essay in Reading 24 puts it) has not always been willing. My attachment has not prevented me from (like most viewers) staring in disbelief at the off-the-scale implausible perils of Kim Bauer, incredulously questioning the time it takes in the 24verse to cross Los Angeles by car or return to the city from the Mojave, wondering how CTU could be so ludicrously incompetent, puzzling how Mike Novick could serve so many roles in so many administrations, wincing at Terri Bauer’s soap-operaish amnesia (and pregnancy), Chase Edmunds’ secret love child, or Jack’s miraculous return from the dead and astonishing on-the-run recovery from an addiction to smack, mystified at the tendency of each day’s breakneck events to peak, like clockwork, at the top of the hour, and achieve climax at the end of 24.2

In a famous passage in The Poetics Aristotle had observed (with Greek tragedy and not television narrative in mind) that “With respect to the requirements of art, a probable impossibility is to be preferred to a thing improbable and yet possible.” “[P]lot,” the Greek philosopher was convinced, “must not be composed of irrational parts. Everything irrational should, if possible, be excluded; or, at all events, it should lie outside the action of the play. . . . But once the irrational has been introduced and an air of likelihood imparted to it, we must accept it in spite of the absurdity.” Does 24 pass Aristotle’s test?

In the age of the Internet we have a new name for the failure to do so. Thanks to Jon Hein’s popular website (and later book) Jump the Shark, it has now become common, after a telling moment on Happy Days when the Fonzie actually did leap over said marine predator, to speak of the moment when a good television show goes bad — when we realize our “favorite show has lost its magic, has begun the long, painful slide to the TV graveyard. . . .” 24 has, of course, inspired its own entries on the website, but revealingly the majority of visitors have insisted the series has yet to take the leap.

It is hard to believe that those who find 24 still shark-free are watching the same series I am. 24, a show that experiments radically with the nature and form of televisuality, has likewise taken shark-jumping to a new level. By jumping the shark incessantly, like clockwork, 24 has transformed the vault into a leap of narrative faith in which the viewer, as breathless and unremitting as the story itself, plunges on, untroubled by doubt or disbelief, misgivings or qualms. Umberto Eco was thinking of one of the great, transcendent films when he observed that “[t]wo clichés make us laugh but a hundred clichés move us because we sense dimly that the clichés are talking among themselves, celebrating a reunion.” The equally transcendent 24 is such a reunion.

Notes

1 Published with permission.

2 For an especially perceptive reading of each and every episode of 24, taking special note of improbabilities and inconsistencies, see M. Giant’s always snarky Television Without Pity recaps.

Bibliography

“’24’ and America’s Image in Fighting Terrorism: Fact, Fiction, or Does it Matter?” The Heritage Foundation. Press Room. 23 June 2006.

Aristotle. “Poetics.” Trans. S. H. Butcher. Critical Theory Since Plato. Ed. Hazard Adams. New York: HBJ, 1971. 47-66.

Cerasini, Marc. 24: The House Special Subcommittee’s Findings at CTU. New York: Harper, 2003.

Eco, Umberto. “Casablanca: Cult Movies and Intertextual Collage.” Travels in Hyper Reality. Trans. William Weaver. New York: Harcourt, 1986. 197-211.

Fessler, Pam. “Chertoff Brings Reality Check to 24 Crew.” NPR. Weekend Edition. 24 June 2006.

Hein, Jon. Jump the Shark. New York: Plume, 2002.

Peacock, Steven, ed. Reading 24: TV Against the Clock. Forthcoming from I. B. Tauris, 2006.

Image credits:

Please feel free to comment.

beautiful corpse or “long painful slide to the graveyard”?

I’m intrigued by some of the questions raised in this article about the relationship of fandom to shows. In fact, this column for me resonates personally in part because I just read Jonathan Gray’s article in this same Flow issue (“Hate, Dislike, Disgust, Distemper, and Distaste”) and I specifically define myself by *not* watching 24….

But not to dwell on that, I would rather simply state that I wish the shows I fell in love with actually all made it to the “Jumping the Shark” moment or moments, rather than being cancelled long before I’m ready to let them go. I don’t want them to survive too long after I realize all the life’s been written out of them (unless there’s a rare surprise and they rejuvenate themselves–thank you Joss Whedon and ensemble for Buffy seasons 5+), but too many shows have been consigned to the graveyard of TV long before their times. While many viewers may wish to have a show die young and in its prime and therefore be remembered that way, I prefer to forgive the painful dying and have seen its full life.

24 “jumping the shark”

This article was interesting, but I fould it hard to follow. I have only seen a couple episodes of 24 and I thought it was great. I dont understand anyone who watches a show and wants to beleive that it is real. We all know that the characters are fake and so is the plot. So why do people try to beleive that what they are watching is going on in real life? We watch show for entertainment. If you get caught up in the difference between real and fake then you ruin the purpose of the show. True, the makers of the show want the story to be somewhat beleivable or else no one would watch, but anything beyon that I feel is takning away the “fun” factor out of television. From someone who only watches TV for entertainment I think the show is great

Shark-jumping? Nope

As Lavery puts it, the definition of “Jump the shark” is when a series goes bad; it’s the moment when a TV show tries too hard to draw in viewers and ends up suffering a decline in quality thereafter. These days, you’ll see on “24” such things as implausibly staged shootouts, torture in its many forms, and even a nuclear explosion here and there. However, consider this: in the very first episode of the show, Jack Bauer shot one of his bosses with a tranquilizer dart, and a seductive female terrorist parachuted out of a plane before blowing it up. That is simply the kind of show that “24” is, and as Lavery points out, many fans agree that the show has yet to make a really huge misstep that it could never rebound from.There were many moments in the fourth season that were badly written and over-the-top, even for me, but the fifth season more than amended those mistakes. Therefore, I feel that the phrase is being used incorrectly within this article. True, the shocks and twists of the various plot threads can become predictable if you watch the show long enough, but jumping the shark? The show is as high-quality as ever if you ask me.I think that Aristotle puts it quite well. “24” could have been a tamer series, but would it have reached the success that it enjoys today? The irrationality that the show constantly promotes is evidently what television consumers want; it’s part of the reason that the show gets such big ratings. Some viewers have their more “intelligent” programming, and some have their mindless entertainment, the so-called guilty pleasures. But I find “24” to be more than just some dumb pleasure for guilt; it’s a hybrid of the two types of programming that I mentioned above.Lavery apparently engages “24” as a fan; I’d say that I engage it as an obsessive. I agree with Steven Peacock in that the show is at times, the greatest thing on television, and at others, superfluously an idiotic guilty pleasure. But because of my status as an obsessive, I choose to ignore the second part of that definition. Aside from Season 4, the good far outweighs the bad in “24”, and may it continue to do so until whenever it ends (which looks to be at least another two seasons away).