R.I.P., F.N.L.

Janani Subramanian / University of Southern California

I need to include an obligatory “spoiler alert” here, since the odd screening schedule of Friday Night Lights (2004-2011) has created a divide between those who have DirecTV (on which the show recently finished its last season) and those who do not (for whom the show’s last season will air on NBC beginning April 15).

This column will probably be equal parts appreciation, critical analysis and eulogy. Saying goodbye to a television show is an odd feeling, particularly because you are saying goodbye to a habit, to a time slot, or, in recent years, to part of a “list” of DVR recordings. The ending of a series also abruptly highlights the fact of television authorship; the continuous experience of a series returning from week to week or season to season perhaps allows viewers indulge in the idea that the series just exists, unending, in some dream-like television database. Friday Night Lights’ primary stylistic feature – the use of documentary-style camerawork – perhaps encouraged the idea that the world of Dillon, Texas would somehow continue week to week, indefinitely. The show did have its own stops and starts, as its future was up in the air after both the first season and the writer’s strike in 2007-2008, leading to premature season finales that tried to awkwardly tie up narrative ends.1

On the subject of continuity, FNL faced the problem that most high school teen dramas face at some point in their run – the fact that their protagonists eventually graduate – but managed to circumvent the awkward transition from adolescence to adulthood (that shows like Beverly Hills 90210 (1990-2000) and Saved by the Bell (1989-1993) clumsily tried to address) with a focus on Coach Eric Taylor (Kyle Chandler) and his family. Perhaps the show’s greatest contribution to the television landscape was a nuanced and developed focus on rural, working-class Americans; the sense of being dropped into a small Texas town was consistently underscored by the show’s commitment to location shooting.2 The characters’ occupations (football coach, high school principal, waitress, nurse, police officer), the modest houses, an open and unflinching attitude towards financial problems – these were the show’s primary markers of its working-class to middle-class milieu.

Then, of course, there was the football, which also helped the show maintain narrative continuity from season to season and contributed, along with the camerawork and location shooting, to a carefully constructed sense of authenticity around the lives of small town Texas residents. The focus on one high school football team (in seasons 1-3, the Panthers, and in seasons 4-5, the East Dillon Lions) fed seamlessly into the series’ alternation of interpersonal, melodramatic storylines; whether rooting for the team, its player or its coach, we as audience members never really suffered from any conflicts of interest. The football itself was filmed in the same documentary realist style as the rest of the show, highlighting the essential moments of each game with familiar conventions – shots of the scoreboard, close-ups of brutal tackles, the sounds of referee whistles and crowds cheering, and glimpses of Coach Taylor’s tense expressions.3 From my own personal sports-watching standpoint, this was the ideal distillation of the essential moments of football into easily digestible melodramatic nuggets. As my partner and I would watch episodes together, I would often think about the show’s gendered address – why would my sports-obsessed partner agree to watch a teen melodrama with me? Did he see it as nighttime melodrama or sports-themed drama? Did the documentary style somehow mitigate the show’s deep investment in the dynamics of heterosexual courtship and teenage angst? Was the football authentic enough to anchor his identification? Whatever the case, our viewing pleasures overlapped enough to keep us together in front of the television from week to week.

In comparison to the show’s nuanced and sensitive portrayal of Coach and Tami Taylor’s (Connie Britton) marriage, the black characters come mainly from broken homes. After the exit of Smash Williams, the show’s main black protagonist is Vince Howard (Michael B. Jordan), who Coach scoops up from the nasty crime-ridden streets of East Dillon and turns into the team’s star quarterback. Howard’s mother (Angela Rawna) is a heroin addict, but her son’s new leaf prompts her to get clean and find steady work, and when his ex-con father (Cress Williams) enters the picture in Season 5, the Howard family gets a sweet glimpse of what “normal” family life is like. But Mr. Howard can only stay away from crime for a few episodes, and it is the demonization of the black father in season 5 that really made me cringe. For both Smash Williams and Vince Howard, Coach Taylor serves as substitute white father, and with the addition of Mr. Howard’s unreliable and unstable black father character in Season 5, the show truly asserts its conservative nature and what George Lipsitz would call its “possessive investment in whiteness.” Lipsitz argues that Americans are encouraged to “invest” in whiteness, both in terms of capital and ideology; on a narrative level, the success of the town, its minority population, and its football players depends on the particular brand of conservative white patriarchy that Taylor represents.4 On the level of production and television markets, the financial viability on the show, particularly with the increased racial diversity of the fourth and fifth seasons, depends on the white family at its center to carry it through an already whitewashed television landscape.

[youtube]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YxTgebdi8lo[/youtube]

I felt increasingly uncomfortable as the last season went on, particularly as Vince Howard’s character suffered under the influence of his black father and only improved under the explicit guidance of Coach Taylor. Camera angles and positions, as well as specific edits and cuts, privileged the relationship between Taylor and Howard as symbolic of the series’ main narrative throughline – not only that sports are a microcosm of life but also that white male leadership is a clean and effective remedy to interpersonal, political and racial dramas. The Taylors eventually move to Philadelphia, and in one of the last shots, the camera pans slowly over black high school football players’ faces, listening raptly, as Coach spouts his various aphorisms. You can take the man out of Texas, but not Texas – or dominant white masculine ideology – out of the man; you can take a show off the air, but it’s hard to forget the ambivalence that it leaves behind.

Image Credits:

1. Dillon Panthers: Clear eyes, full hearts, can’t lose

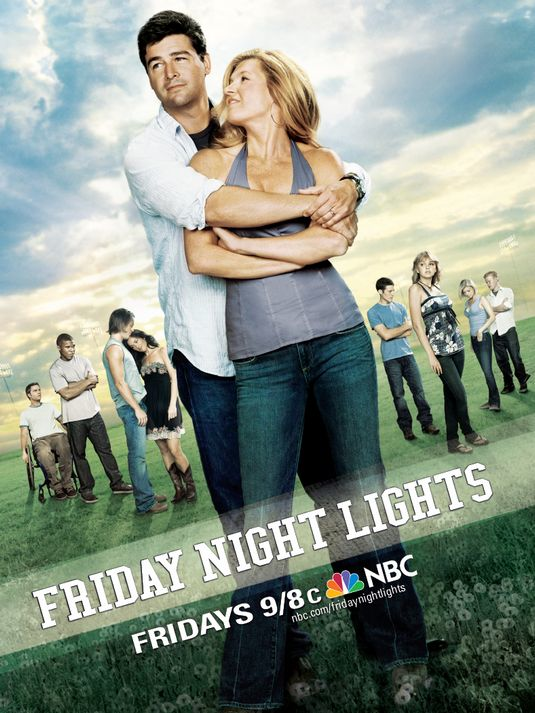

2. Focusing on the Taylor family

3. East Dillon’s Vince Howard and Coach Taylor

Please feel free to comment.

- http://web.archive.org/web/20080413145255/http://community.tvguide.com/blog-entry/TVGuide-Editors-Blog/Ausiello-Report/Ausiello-Scoop-Race/800032760?rssDate=12345678 [↩]

- http://flowjournal.org/2008/06/i-don%E2%80%99t-think-we%E2%80%99re-in-hollywood-anymore-television-series-go-on-locationalisa-perren-georgia-state-university/ [↩]

- I can’t find a great way to fit this into my column, but a large part of the show’s Internet fandom was devoted to the emotional resonance of Coach Taylor’s…hair. From episode to episode, Chandler perfected the tousled look of a man who cared little about appearance – his hair just oozed earnest frustration. See the Television Without Pity forum, “What would Kyle Chandler’s Hair Say?” http://forums.televisionwithoutpity.com/index.php?showforum=902 [↩]

- George Lipsitz. The Possessive Investment in Whiteness: How White People Profit from Identity Politics. (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2006). [↩]

Another great column, Janani. I especially appreciate your criticism regarding Coach Taylor’s white patriarchal symbolism, and I wonder what a comparison of the Taylors and the Tuohys from The Blind Side in this regard would produces. Obviously, such a comparison would be problematic because of the different forms, aims, and modes of address, but there are some interesting similarities in terms of some dynamics as well as relationship to the “reality” that inspired their stories.

Thanks for the comment, Charlotte! I never thought about the relationship to the Blind Side, but that’s a great comparison. I was thinking yesterday (during the Oscars) about how Sandra Bullock won the Best Actress Oscar last year and the kind of overarching narrative Hollywood cherishes about white saviors and black victims. Even though The Blind Side is a true story, Sandra’s win raised questions about the way mainstream culture likes to celebrate and reinforce these narratives.

I don’t think the issue is necessarily white-and-black as it is Taylors-and-everyone else. When in doubt, go to the Taylors for guidance. I think every teenaged character on the show seeks guidance from one of them at one point or another. I also don’t necessarily agree that it shows all the black characters as coming from broken homes. Yes, Vince’s family was broken but Smash’s family wasn’t a broken household (although his father was killed while he was a kid) and Jess had her entire family intact (as far as we know; her family was never really examined all that closely but we did see her siblings and father regularly). On the flip side, Matt Saracen had to look after his dementia-stricken grandmother after his father had run off to war and his mother had just run off. Tim and Billy Riggins had no parents; we saw their father for a few episodes in the first season and Tim throws him out after discovering he had stolen a camera from the football office and I don’t ever recall his mother even being mentioned. That’s probably the most broken home in the show.

Maybe the more true fact is that the racial component to the show came around more in the last two seasons than in the first three, which is probably the result of trying to save the show again and also the change in narrative, where Coach Taylor leaves the more-rich Dillon for the completely poor East Dillon.

Very incisive points. The shot of the all-black Philly team listening raptly to Coach Taylor did irk me out of what was otherwise a very satisfying final scene.

There are definitely racial undertones of Friday Night Lights that are be heftier and more troubling than a lot viewers (and, at times, the show) seem to want to acknowledge. However, I’m not sure the evidence you point to is quite there. To echo Wally, to claim broken homes as a trait of the show’s black characters is reductive. Almost all these kids have families and home lives that are deeply flawed, if not outright disastrous:

Lyla– Dad cheats, Mom leaves.

Tyra– Single mom with abusive boyfriends.

Matt– Father at war, then dead. Absent (mostly) mother

Riggins– No parents, save a brief and faulty reconciliation.

Becky– Mom leaves, Dad is an abusive, barely-there trucker with a new trashy wife.

Ruckle– Itinerant family b/c of Dad.

J.D–Abusive, controlling Dad.

And, also, the black kids, although I’d argue that their home situations are, on the whole, portrayed more positively than the white kids’:

Jess–No mother, but father supports a strong family.

Smash– Single mother, but the overall family is intact and tight-knight.

Waverly– Caring, priest father (can’t remember a mother, but then, didn’t FNL want us to forget everything about Waverly anyway?)

Vince– Former addict mother, criminal father; however, they did get some nice moments together that was not afforded to pretty much any other non-Taylors adult couple. I wouldn’t say Vince’s father was ‘demonized’. His primary antagonistic force was trying (in earnest, importantly) to help Vince succeed, which bristled Coach. But it bristled Coach not because he was black, but because his actions completely insulted Coach’s authority in the domain of football, an authority Taylor earned by merit of experience, not race. In many ways, this was the same case with Joe McCoy, who I’d say was a far more cartoonish and unnuanced villian than Vince’s dad.

Anyways, even if you dispute this on a racial level, what the show is really saying here, and what is really a central theme to the whole show, stands: the typical (Middle) American family is in rapid disrepair. The Taylors are the bulwark that withstands the rush of that dissolution. That is why Coach Taylor is not the “surrogate white father” to the likes of Smash and Vince. He is just their “surrogate father”, just as he was to white Matt Saracen, Jason Street, and Tim Riggins. I’m not saying that if ‘the Taylors’ were black that the show wouldn’t be changed on a fundamental level. But, to be faithful to the depiction of that universe, ‘the Taylors’ are necessarily white. Definitely, as you mentioned, it’s also partly necessary for audience garnering and retention. But I don’t think that every aspect of the show is quite as colored by color as you indicate. Certainly ambivalent, arguably conservative, but not, in my opinion, unfair.

I have to agree completely with Tyler’s very thorough explanation of each character’s family situation. Vince’s family situation is just one of many. It’s racialized because the show wants to suggest — but never directly say — that there’s a particular way black family dysfunction manifests itself in America (prisons, drugs, violence — but of course other characters go through this as well).

I think the problem Janani highlights is the problem of television’s need to have a white male character at the center of the narrative. I’ve had many debates about the racial politics of any number of diverse and ambitious shows (from Glee, Community, 30 Rock, Mad Men, The Sopranos, etc.), and the bottom line always ends up being: it’s really hard to have a progressive/transformative racial politics when the center of the narrative is white, particularly a white dude.

Ultimately, those narrative decisions are based on the network’s desire to get those viewers, because they’re presumably hard to reach. We should demand even more ambitious storytelling (The Wire is a decent example), but we also shouldn’t dismiss the efforts of some writers to work around those constraints, which is what I think FNL tried to do — pretty successfully, in my view.

Your point at the end about the black players in Philadelphia listening to the white head coach doesn’t note one truth: that most good football teams at all levels are largely built with that same dynamic. Coach could have coached a bunch of white kids but a team with nothing but a bunch of white kids likely wouldn’t be very good and thus would be beneath a high school coach of his stature. The Green Bay Packers just won the Super Bowl with a white head coach, a white quarterback and a primarily black roster. The same is true of almost all Super Bowl winners, college football national champions, and high school state champions throughout the country. I think FNL’s portrayal of this fact adds to (or at least maintains) the authenticity of the product.

I liked how you said 90210 and SBTB trying to move from high school to college was done “clumsily.” The best is how in both shows, at the end of the high school run, all the characters go out and apply to all of these various different colleges and in some cases even accept their acceptance, yet in the end they all end up at the same place. Even more awesomely, they all ended up at California University-—in both shows! I’m still mad that the 90210 and SBTB The College Years writers didn’t join forces and merge their two shows. You can’t tell me that you wouldn’t religiously watch (and re-watch) a show that included Brandon Walsh, Zack Morris, Jessie Spano, Screen Powers, Dylan McKay and Donna Martin. The only problem would be how to handle the Valerie Malone/Kelly Kapowski conundrum but I’m sure something could have been done to correctly and properly solve that.