The Visual Style of Jet Lag in the Work of Fiona Tan

Konrad Ng / University of Hawai’i at Mānoa

In The Global Soul: Jet Lag, Shopping Malls, and the Search for Home, Pico Iyer describes jet lag as “that peculiar state of mind—or no-mind—that belongs to the no-time…[a] no-man’s-land, a realm of spaced-out dreaminess where something in one doesn’t engage, and something else comes loose.”1 For Iyer, jet lag describes the global cultural and technological forces at work today. The present is populated by “global souls” who possess fragmented senses of home and the capacity to access multiple places, far and near, past and present, at a rapid pace. While jet lag may be a biorhythmic condition that describes the effects of changing time zones, Iyer writes that the disorientation of jet lag is becoming definitive:

Humanity today is facing all kinds of sudden jerks it’s never known before, and many of us embrace this phenomenon…without knowing what the consequences will be. The average person today sees as many images in a day as a Victorian might have in a lifetime; but compounding, and confusing, this are the shifts in place and mind we experience…We wake up, orphaned, in West Hollywood and go to sleep, surrounded by our parents, in medieval Katmandu; we zigzag across centuries as if they were just settlements in a village.2

Indeed, the New York Times reports that the multitasking and information overload made possible in the technological global age affects our attention span and challenges the demand to be present in our personal relationships. Reporter Matt Richtel writes, “scientists say juggling e-mail, phone calls and other incoming information can change how people think and behave. They say our ability to focus is being undermined by bursts of information…The stimulation provokes excitement—a dopamine squirt—that researchers say can be addictive. In its absence, people feel bored.”3 I want to suggest that jet lag—that is, the labor of finding focus amid distracting and disorienting pulls—can be a concept for thinking about the work of artist, Fiona Tan. As a woman of Chinese-Indonesian-Australian-Scottish descent who was born in Indonesia, raised in Australia and lives in Amsterdam, Tan embodies Iyer’s “global soul.” Her work expresses a form of jet lag that encourages a critical break with the plugged-in present.

When thinking about the temporality of the present, it is tempting to appeal to visceral concepts to match its rhythms. The observations of Iyer and Richtel bring to mind the cinematic aesthetics of what David Bordwell calls “intensified continuity,” the dominant visual style of contemporary American film that uses “brief shots to maintain the audience’s interest but also making each shot yield a single point, a bit of information.”4 Bordwell notes how the emergence of cinematic tactics such as increased editing, breaking long shots with “wipe-by cuts” to reframe the on-screen action, close framings in dialogue scenes and increased camera movement “intensify” the visual continuity characteristic of classical filmmaking.5 The resulting increased continuity conveys rapid pops of visual information that engage spectators via editing and camerawork rather than by the force of the narrative. Bordwell writes,

[t]he mannerism of today’s cinema would seem to ask its spectators to take a high degree of narrational overtness for granted, to let a few familiar devices amplify each point, to revel in still more flamboyant displays of technique—all the while surrendering to the story’s expressive undertow.6

I cite intensified continuity because its visual style reflects the stimulus-response tempo and multiplicity of the present, what Iyer described as the “sudden jerks” that humanity “has never known before [but that]…many of us embrace” and, as Richtel reported, “[i]n its absence, people feel bored.”

But there is another cinematic technique, one that is present in the work of Fiona Tan, that stands in contradistinction to the editing and camerawork of intensified continuity. I am referring to a deep focus long take: a sequence presented without cuts during which the entirety of the scene remains in focus. Andre Bazin contends that the long take allows the viewer to let his/her attention wander the space of the scene. As the action unfolds, the meaning of the scene becomes open to interpretation as the viewer must make his/her own sense of the on-screen action and the meaning of the sequence. As such, the technique shifts the labor of interpreting the narrative to the spectator, a move that differs from intensified continuity’s reliance on visual style. Bazin states that the long take “affects the relationships of the minds of the spectators to the image, and in consequence it influences the interpretation of the spectacle…it implies, consequently, both a more active mental attitude on the part of the spectator and a more positive contribution on his part to the action in progress.”7 Tan uses the visual style of the deep focus long take to craft an experience that asks the spectator to focus and engage in interpretation as they align time zones of meaning.

Tan’s May You Live in Interesting Times (1997) uses the genres of documentary and autobiography to map the time zones which inform her heritage as a global soul. N.T. (Leidsester) (1997) and Provenance (2008) offer interpretations of historical and contemporary zones of life in the capital of Tan’s country of residence, which simultaneously differ and overlap with her sense of home. The Changeling (2006) streams through monitors to offer a meditation on the soundness of memory, biography and self through portraiture. A Lapse of Memory (2007) questions the foundational role of temporality and memory in the construction of biographical narrative. Tan’s Rise and Fall (2009) stands out as an exercise in jet lag. The two-screen installation is composed of long takes depicting natural landscapes such as a waterfall and women (or one woman at different periods in her life). The juxtaposition of the imagery oscillates between synchronous and asynchronous visual cultures to create an enigmatic pattern. The inclusion of diegetic and ambient sounds adds a haunting quality to Rise and Fall’s visual exercise of focus and interpretation. Tan uses the long take to draw spectators into a state of jet lag. Each screen represents a time zone of meaning that allows spectators to construct correspondences between and among the imagery. By doing so, Rise and Fall creates a critical break as spectators must exercise narrative skills of interpretation.

Pico Iyer’s work and Matt Richtel’s article suggest that the vibrancy of non-stop global civilization is addictive. Here, jet lag—that physical and mental state in which we realize the pull of time zones and exert ourselves while trying to align zones of meaning—may be a useful side effect of globalization’s whirl. A global soul like Fiona Tan offers aesthetic interventions that mimic the critical break afforded by jet lag; in this sense, jet lag may be something that we will want to embrace.

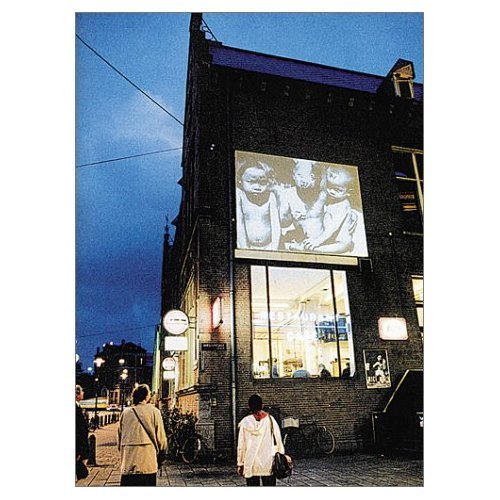

Image Credits:

All images compliments of the Smithsonian Freer and Sackler Galleries of Asian Art.

Please feel free to comment.

- Pico Iyer, The Global Soul: Jet Lag, Shopping Malls, and the Search for Home (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2000), 59-60. [↩]

- Ibid. 60. [↩]

- Matt Richtel, “Hooked on Gadgets, and Paying a Mental Price” New York Times, June 6, 2010, http://www.nytimes.com/2010/06/07/technology/07brain.html. [↩]

- David Bordwell, “Unsteadicam chronicles” Observations on film art, August 17, 2007 http://www.davidbordwell.net/blog/?p=1175. [↩]

- David Bordwell “Intensified Continuity: Visual Style in Contemporary American Film” Film Quarterly, Vol. 55, No. 3 (Spring, 2002), 16-26. [↩]

- Ibid. 25. [↩]

- Andre Bazin, “The Evolution of the Language of Cinema” Film Theory and Criticism, 6th Ed., ed. Leo Braudy and Marshall Cohen. 41-53 (New York: Oxford University Press, 2004), 49. [↩]