Strictly Dancing Newsreaders

by: Nichola Dobson / Independent Scholar

Reading Alan McKee's article in the previous edition of Flow in which he discusses mass television audiences and his own preferences for reality television reminded me of some questions I had been thinking about recently after teaching classes on discourse and ideology in news and reality television (among other things). In this column I will attempt to respond to some of his key points and how they relate to the current issues surrounding the increasing influence of reality television, specifically in the UK.

I was never particularly interested in the Big Brother concept beyond psychological experiment and have no interest in celebrity magazines and indeed often concerned with the ideology being presented and consumed by the masses. However in terms of examining reality television as purely television, I am interested in the development of the genre which has so quickly spawned so many sub genres and defined and influenced much of contemporary society (at least in Britain).

Personally I enjoy scripted narrative drama such as The Sopranos, Lost and Doctor Who, however I agree with Mckee's suggestion that we tend to study those which interest us most and I have personally been guilty of being overly critical of reality TV at times. (Though even the British viewers of the last series of Celebrity Love Island agreed with me as it delivered it worst ratings since the show began). The few reality shows I have watched are more of the 'already skilled, competing and receiving constructive criticism' such as Hell's Kitchen, Ramsay's Kitchen Nightmares and even Tommy Lee's Rockstar Supernova. However, this appeals to my interests in cooking and alternative/rock music rather than the warbling pop of the Idol franchise and deliberate humiliation of contestants by the ego fuelled nastiness of Simon Cowell.

Most of my research has focussed on genre and generally narrative television, but after teaching required me to prepare a class on the discourses in reality television, and another on the construction of news programmes I began to think about reality TV more broadly.

The key point from McKee's paper that I would like to explore here is his suggestion that “the mainstream of the viewing public, has proven themselves to be less superficial, less concerned with spectacle, and more committed to traditional values of what counts as art, than I am.” (Flow volume 5, issue 5). This may be the case when his favourite from Australian Idol was not chosen; however I am curious to what extent this may be true when applied to other reality shows, in particular the case of Strictly Come Dancing.

In the UK we have now seen four seasons of Strictly Come Dancing, which I know spawned Dancing with Stars in the US, but am unsure as to the extent of its influence elsewhere. For those unaware, the premise is, a 'celebrity' is paired with a professional ballroom dancer and they compete over several weeks with similarly paired contestants. The audience votes for their favourites and each week a couple is eliminated. And of course there is a panel of judges, each cast in pantomime stereotype to deliver their 'expert' verdicts. So far so formulaic, but in the first season in Britain, the audience was confronted with a slightly unusual celebrity, in the form of a leading news anchorwoman, Natasha Kaplinsky. Newsreaders in Britain are rarely seen away from their desks, let alone in full ballroom dance mode.[i] After several weeks it became apparent that Natasha could dance fairly well, and she and her partner won the competition. Clearly she was perceived at this point, by the producers at least, to be a celebrity of sorts, and the tabloids followed with a new interest in her private life, previously unknown territory for television journalists.

One of the obvious effects of appearing on a reality show, celebrity or otherwise, is the inevitable crossing of the private/public space. In Natasha's case her personal life was heavily scrutinised but she also proved so popular that she was promoted to anchorwoman of the six pm news, the lead slot for newsreaders in Britain. It could be viewed that she was being rewarded for her dancing ability and popularity.

My students suggested that this was far from problematic. The seriousness of the news was not being compromised by the frivolous links to the dancing show, instead the popular Natasha was making the news more accessible to the mass audience. However this would suggest that the audience in this case were just as superficial and concerned with spectacle as McKee suggests he is.

Is this important in the realm of television news? Does it have an effect on the notion of journalistic integrity or are the news anchors merely parts of the network construct which decides which news is worthy of their/our attention? Or am I taking this too seriously because I like my news delivered to me in a, well less glamorous way and don't have any interest in celebrity dance shows?

I am curious about the effects of this relationship between reality television and news programmes and wonder how the powers that be perceive the mass audience, particularly when the station which broadcasts both the dance show and the particular news programme is the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) famous round the world for its quality journalism and programming. We do have a great deal of choice in our news consumption in Britain and people are free to choose, as with any television, which they watch. I suppose my question of the merging of entertainment with news rose from the very fact that the BBC sets itself apart from other news programmes and tries to suggest a level of quality not seen elsewhere, particularly on cable/satellite television.

The relationship between Strictly Come Dancing and the BBC news developed further when another news reader, Bill Turnbull, took part in a later series of the show. During the last series the BBC Breakfast news magazine show became a virtual advertising feature for the series, interviewing contestants and sharing experiences. Even the competing public broadcaster ITV has gotten involved with one of their newsreaders currently competing.

It seems then that the relationship is continuing and suggests that if my students' notion of an increase of popularity for newsreaders helps the mass audience receive more news is correct then the mass audience is as superficial as McKee claims to be.

I understand the appeal of some of the current crop of reality television and enjoy mindless entertainment occasionally but I think there is perhaps a line at which genre hybridisation should stop and personally I think that is at news programmes.

So as the newest series of Celebrity Big Brother begins I will continue to avoid it and instead enjoy the new series of ER, Desperate Housewives and CSI which have just come back to British TV. Sorry Alan, they don't have dancing in them but I just don't have time for narrative shows and reality television so I'll choose on a show by show basis and see how much my PVR can record.

Please feel free to comment.

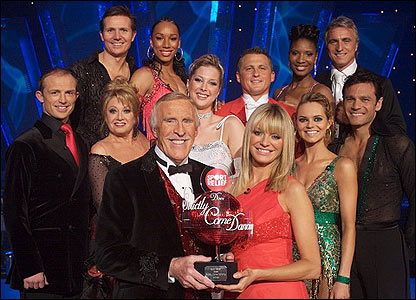

Image Credits:

1. Strictly Come Dancing

2. Strictly Come Dancing cast

3. Strictly Come Dancing team

Please feel free to comment.

[i]There was something of an outcry in the 1970s when newsreader Angela Rippon appeared on a comedy Christmas special with Morecambe & Wise and danced with them, daring to show her legs. She later went on to present Come Dancing, so perhaps there is an historical connection between news anchors and dance shows?

Thinking about the implications of the crossovers between Reality TV shows and newscast, I would call the attention about how these Reality TV Shows may hurt the very institutional level of the television broadcasting companies. Mexico has a duopoly in the television industry, where the networks Televisa and TV Azteca have around the 90% of the national market. The relation between Televisa, the biggest producers of Spanish language television in the world, with TV Azteca a bold new comer with aspirations of becoming part of the world’s second media tier can be described as war. This battle permeates production, programming, marketing and institutional strategies. Within this context the phenomena produced by Reality TV shows as described by Dr. Dobson have produced perverse scenarios. Successful formats as Strictly Come Dancing, triggered the openning in Mexico of two shows with one week of difference, Dancing for a million (Bailando por un millon) in TV Azteca, and Dancing for a Dream (Bailando por un sueño) in Televisa. This bis a bis confrontation of reality shows with identical format has been common in the Mexican television in the last five years. The match between the prograsm with the same format triggered: first, threats of legal actions coming from each network in relation to violation rights agreements, accussations of cheating, plagearism and deshonesty to each other network. This situation produced a environment of nasty declarations that create confusion in the audience about who is lying and who is not. The point here is that the nature of the battle between networks particularly in the case the Mexican versions of Strictly Come Dancing produce an institutional harm damaging credibility and trust. Second, has to do with the institutional level reflected in the feudal relationship that each network has with their talents. There is no way that talent could be allowed to appear in the other television network. However the size of the Televisa media conglemate has allowed it to dominate the Mexican star system in television, music, film, magazines, sports and so on and so forth. Televisa’s Dancing for a Dream defeated TV Azteca´s Dancing for a million. But in the process TV Azteca used all the people that was able to use. Within the process not only actors or singers, but anchors, speakers, and reporters from news programmes where used by TV Azteca to fit the program needs. The very institutional identity of the company is touched by the contest the spectacle and their implications. And third, the ratings rule. I am not sure about the United Kindom, but newscasts in Mexico do fairly poor in ratings in comparison to the reality TV shows and telenovelas. Newscasts may have an average from 13 to 18 points of ratings meanwhile Reality TV shows, as Televisa’s Dancing for a Dream, was able to achieve 30 rating points and more. The success was apparent when in Televisa´s Christmas Celebrations the most powerful executives from the company danced in a contests that emulated the Reality show where the president Azcarraga Jean had a priviledge vote of wich top executive was the winner, the contest was call Dancing with an Executive.

Performing objectivity

Thoroughly enjoyed Nicola’s piece. It raises an important question – why should it compromise someone’s performance as a newsreader if we know that they have legs? That they dance? That they are human beings? I think it’s because of the myth of objectivity – that if newsreaders are not seen to be human beings, then we can pretend that the news they read is simply ‘the truth’, delivered from God, not written from particular perspectives by human beings. Hence the reason that early radio newsreaders weren’t allowed to give their names in Australia – it would have compromised their objectivity. Also, why women were not allowed to read the news for a long time – the argument was they would distract viewers from the news. And why the newsreaders still wear suits or formal wear. Would it make the news any less objective if the person reading it wore jeans and a T-shirt? Why? Personally, I think the more informal news presentation is, the better – it reminds us that these stories have been researched and written by human beings, just like us, who have their own interests, perspectives and passions – which, of course, inform the stories they choose to research, how they research them and how they write them.