Television, Ecotourism, and the Videocamera: Performative Non-Fiction and Auto-Cinematography

by: Adam Fish / UCLA

In two first-person cinematographer ecotourist programs, Survivorman (Science/Discovery) and Caught in the Moment (Animal Planet), the difficulties and joys of being a small camera crew are as important as what the cameras record. Camera-crews-as-characters, cameras-as-props, the filming of tourists filming themselves–does this technological reflexivity ad nauseam signify industrial solipsism, a mise en abyme, the foregrounding of the background, or just an audience interested in television production?

Mixing the technological determinism of apparatus theory with transcendental phenomenology to measure the intersubjective distances that exist between the “bodies” of the media-producer, the media technology, and the media produced, I will define techniques of the sub-genre of first-person, reality-based adventure television: self-cinematography and performative nonfiction. Intersubjective intimacy is achieved in Survivorman by closing the distances using these techniques, while conversely in Caught in the Moment distance is increased and intimacy repressed. In the process, ideologies of tourism are interpellated in the viewer.

Survivorman

Survivorman is a high-concept extreme adventure program that features one man, Les Stroup, dropped off alone with nothing but a half-dozen video cameras for seven days in one of the world's least populated and ecologically dangerous locations. He is his own camera crew. His only chore is to survive and film his survival without food, water, or shelter.

Caught in the Moment

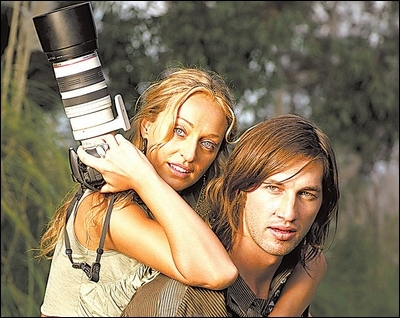

The premise of Caught in the Moment (CitM) is Vanessa Garnick and Tristan Bayer, two gorgeous, romantically-involved cinematograher/hosts collecting footage of rare anmials for a nature “conservation video.” Three camera perspectives are possible in CitM, the hosts filming nature, the hosts filming themselves, and the Animal Planet crew filming the hosts filming turtle eggs and white bears.

Performative Nonfiction

I use the term performative nonfiction to define an affective, honest, or indulgent “excess” in subjective documentary. Performative nonfiction emerges from autobiographical confessions, exaggerations, and projections. Performative nonfiction includes apparently spontaneous dialogue and body movements produced when a camera inspires the surmounting of quotidian embodiment. Behind-the-scenes moments move to center stage in performative nonfiction.

Performative nonfiction begins with the belief that the cinematographer is an active participant in the production of the document. Like interactive cinema verite before, performative nonfiction takes the camera not as a limiting filter to the realization of the real but as inspiration to show the ecstatically real. Ostensibly, every documentary–from observational to mockumentary–is a performative nonfiction. But few programs attempt to create an environment and an event where nonfiction becomes performative.

Auto-cinematography

Auto-cinematography takes a lead from auto-ethnography in insisting that objectivity is impossible and responsible cross-cultural research begins with self-knowledge. Auto-cinematoghaphy continues with the interactivity of cinema verite by acknowledging the filmmaker as an event maker while simultaneously requesting the filmmaker to begin with oneself as the source of knowledge about the other. Practically this means filming oneself, producing a faithful video-diary, shot while in the transprovential flows of travel and adventure.

Reflexivity: Talking to Oneself v. the Second Camera Crew

In a culture of Photoshop, “imbedded” reporters, and recent scandals in photojournalism, we are skeptical of the still and moving picture image. A souvenir photograph in front of a famous obelisk is no longer enough to prove the appropriated power of visiting a sacred place. An added layer of veracity is required. We want a picture of you taking the picture. Added layers of verification, yes, but also dynamic corporeal and technological layers recursively fuel the pleasure of a reflexive text.

In CitM, the documentation of documentation is provided by the Animal Planet camera crew that films the protagonist camera crew. The duo from CitM talk about filming, and express their goofy joy at getting a good shot of a dancing crane. In Survivorman, reflexivity is achieved when Stroup reflects upon the added difficulty of filming himself when he is in hypothermia or parched dehydration, as well as telling us when he leaves a camera behind because of its burdensome weight. In both programs, through pictures of cameras and discussing the program-making process, media production–usually left behind-the-scenes or on the editing bay floor–is foregrounded for entertainment.

Camera Distanciation in Caught in the Moment

By exposing the industrial machinery of theatricality, Bretolt Brecht explored distanciation–a rupturing of the audience's drama-soporifics. The industrial machinery in CitM–cameras everywhere as props and tools– is intended to bring the audience closer to the means of production, which, in this program, is also a path of seduction–the erotics of television production. The cameras as a sex-toys –Deleuze and Guattarian “desiring machines”– are intend to break Brechtian law by making the technologies the erotics.

It doesn’twork with three or four cameras burning DV and celluloid from multiple perspectives and motives, the televised program primarily consists of images shot by the Animal Planet crew of the hosts filming and reflecting on their excitement. The super 8, mini HD, and 16 mm cameras toted by the hosts are mere props.

With a large degree of extra-diagetic narration, naturalist editing, and the cameras-as-props whose footage is rarely used in the glossy, hyperactive, digitally manipulated, and non-linear “conservation music video,” the cinematographers are distanced from the narrative, the backstory recedes from the screen, and CitM is untrue to its mission –the romance of making videos about endangered mammals.

The veracity added to an image when it is shown along with the making of that very image is voided when the cinematographers and their cameras are mere props and the images are not their own. The camera-crew-as-characters is a gimmick–not a tool for editorial polyvocality and greater transparency.

The Non-Performative in Caught in the Moment

CitM looses its potential of foregrounding the backstory by shying away from the risqué subtext of two sexually and romantically active hosts. While retailing itself as a behind=-the-scenes look at a sexy film crew in romantically ludic –near honeymoon– work, CitM only reveals these cine-hosts as sexless simulacra of tantric-cinematographers. The product, though fascinating in theory, is neutered of its sexuality and multitierd reflexivity. The lusty backstory is repressed for a G-rating. Animal Planet and its interests in a proto-teenage and family audience is to blame for this dulling containment.

Camera Embodiment in Survivorman

With no crew, camera and host are –corporeally– closer. With less mediation, fewer distinctions exist between the original footage and the televised product. In Survivorman, the camera apparatus, the body of the protagonist, and the final edited program retain greater continuity and achieve accurate representation of television making. Few filters–and less distance–exist between the camera, Survivorman's body, and the televised product.

With the exception of the introduction, all narration is spoken in-the-field, the camera becomes a survival tool or threat to survival, the stock ratio is small, and with the televised product being temporally linear –the first mini DV tapes begin the show and the last DV tape ends the show– Survivorman closes the gaps between the fore and background. Discovery Channel, guided by several successful programs that feature charismatic first-person protagonists undergoing physical challenges (Dirty Jobs, Going Tribal) may be more comfortable with this performative posthuman self-cinematography than the pre-pubescent friendly Animal Planet.

Auto-Cinematography and Performative Non-Fiction in Survivorman

Out of necessity, auto-cinematography dominates the cinematographic style of Survivorman. He is his crew. The digital footage collected by Survivorman provides for the editors a wealth of handheld activity with which to represent the dangerous–not “fly-on-the-wall” but “on-the-fly”– death-peering adventures. Auto-cinematographic mayhem, as well as the pedestrian cadence and inquisitiveness of cinema verite cinematography, dominate Survivorman. Unlike CitM, which relies on Amimal Planet's camera crew (with steady-cams, pre-prepped shots, tripods, and three camera crews), Survivorman relies upon the film footage shot by the solo progagonist with an assortment of film cameras with various states of obfuscating lens moisture –and existence as a corporeal concern– to provide a living or dying handheld look. The cameras are so near to the body that his sweat fogs the lens and endanger his life. Survivorman retains much of the immediacy and vibrancy that comes with spontaneous cinematography, unrehearsed and unscripted performance, and near in-camera edits. In contrast to CitM, which represses erotic urges, all the gruesome details of being an excreting, starving, insect-devoured body are included in Survivorman. Like another Discovery Channel program, Going Tribal, gustatory and bodily excess are prominent spectacles.

The emphatic commitment to auto-cinematography in bodily difficult situations inspires Survivorman towards corporeal transcendence. The camera is an excuse, a drug, a mantra, a totem to immediately go beyond his body pain.

This is the martial art of performative nonfiction.

Ecotourism, Cameras, and Commercials

Nature is a backdrop for two ecofantastic adventures. It is a romantic getaway in CitM, typified by the working vacations with lovers — the honeymoon. It is a fear-facing extreme trip, something like pychedelic mountaineering, in Survivorman.

Jet travel and the videocamera are ubiquitous for both television and middle-class eco-adventurers. Both programs make travel and video machines part of the narration. A helicopter may save Survivorman at any moment, they all come and go by jets, the miniDV tapes survive, and Discovery and Animal Planet broadcast the programs. The armchair adventurer enjoys what she never enjoyed.

Photography is integral to tourism. Tourism is in the travel as well as the retelling. Camera wielding tourists fantasize about being the first to document exotic landscapes. Tourist photographers retell their adventures with these visual aids. While cameras are necessary to today's traveler, TV is the ultimate picture-storyteller to the widest possible audience. These programs make the camera a character and in doing so figure the middle-class tourist-photographer–and their fantasy of photographic fame–into the picture.

Jetset recreation–it's safety in danger, the romance in travel, the camera-on-tour–is sold to the travel, insurance, car, flight, credit card, and camera corporations that capitalize on expensive world travel and who dominate advertising on Animal Planet and Discovery Channel.

Bourgeois travel is a safe danger, television even safer tourism, but consumerism is travel without travel without end.

Image Credits:

1. Vanessa Garnick and Tristan Bayer

2. Stroup setting up his camera

3. Garnick and Bayer

Please feel free to comment.

Wow, Survivorman sounds insane – when you say

“Survivorman is a high-concept extreme adventure program that features one man, Les Stroup, dropped off alone with nothing but a half-dozen video cameras for seven days in one of the world’s least populated and ecologically dangerous locations…. His only chore is to survive and film his survival without food, water, or shelter.”

it almost sounds as if he has to survive without finding any shelter, eating or drinking – which couldnt be the case???

Anyway will definately look into a few of these shows. thanks.

very interesting article. I liked it so much. thank you for sharing this post with us.