Convergence as Conflict: the Tasing of Andrew Meyer

By: Ted Gournelos / University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign

This summer I experienced an ethical shock of sorts when I arrived to teach a summer course at the University of California, Berkeley. The associations between Berkeley and the free speech movement, as well as the broader campus history of protests against the war in Vietnam, the wars in the Middle East, and the exploitation of graduate students by the University system were foremost in my mind. However, despite my positive experiences with students and faculty at Berkeley, I was haunted by an uneasy feeling that the institution was masking its own policies through a history of conflict.

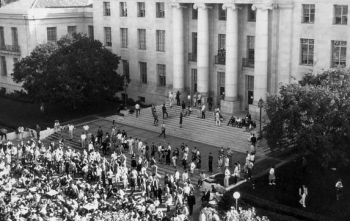

The appropriation and reframing of past protests was evident in the propaganda of student tours, and the establishment of the Free Speech Café, complete with tables laminated in relevant newspaper clippings. Simultaneously, however, the largely progressive students and faculty recognized that the University of California system was an immense bureaucracy, and many of them felt ignored or abused by it. The under-the-radar handling of the “tree people” protesters against the building of a new sports complex a perfect example of this dissonance in Berkeley’s brand identity. After students, alumni, and area residents took to living in a grove of trees to prevent their clear-cutting, university administrators erected a fence around the trees, denying the protesters access to further supplies. Through this experience, I realized how university spaces have become dangerous places for protest, in which “making a fuss” is neither polite nor tolerated. Protest movements on campus, it seems, have changed, and the tasing of Andrew Meyer at the University of Florida on September 19th provides only the most recent and troubling example.

In the past week, the United States has witnessed a startling and horrifying example of what Henry Jenkins recently called “convergence culture.” For Jenkins, convergence implies a movement towards media that is networked and user-based, leading to new ways in which communications technologies can be used in what de Certeau hailed in 1984 as the oppositional “practice of everyday life.” The recent media frenzy surrounding the “arrest” of 21 year old University of Florida student Andrew Meyer, including his torture with a taser by a police officer while he was on the ground surrounded by several officers, has been watched hundreds of thousands of times on the internet and television. It is important of course to address the event itself, as is currently being done on blogs, newspapers, and other media throughout the world. However, I will not attempt to make much sense of the event here, beyond a few brief comments. I would instead like to understand what happened through a look at the implications of “convergence culture” and the possibility not for the community and consensus implied by Jenkins’ work, but rather a conflict-based approach to media and culture industries.

The Tasing of Meyer

First and foremost, the nature of the crime is horrifying. I do not of course refer to the “crime” of which Meyer was accused, “resisting arrest” and “assaulting an officer,” but rather the torture of an unarmed and relatively subdued young man in a state-run university setting. There are multiple videos of the event online, all of which clearly show Meyer surrounded by police both during his questions and afterwards when he is being led away. The Washington Post blog attempts to frame what we see in the video (“There are some important things worth noting BEFORE you watch the video…”) by telling us that audience members initially applauded his arrest, Meyer was supposedly known for making a similar “fuss” at other events, Kerry’s lecture had lasted a half-hour too long, and Kerry himself tells the crowd in the background that he will answer Meyer’s questions. However, the Post’s framing is unsuccessful.

There are several reasons for this, primarily the nature of the video itself. The unarmed man screams first that he has done nothing and that the police have no right to arrest him; as the incident escalates, he cries out for help, and finally in sheer pain. The inaction of audience members (and the smiles on some of them) during the incident push the horrific scenes further, and some of the videos of the incident finish with some audience members trying to stop the police, who then push them (and their cameras) away. Furthermore, the arguments posed by the Post are tenuous at best. Audience applause is no way to judge a video of police brutality, and despite University systems’ attempts to make us reject students who “make a fuss,” whether that is against a racist mascot (as it was at the University of Illinois) or the exploitation of graduate students (as it was at New York University), images and video of peaceful students being arrested or beaten doesn’t quite work with a progressive brand identity.

It is here that we should see the third, and perhaps most important, aspect of the Meyer scandal. If we look at the event in terms of classical student protests, we see a simple question/answer session that “got out of hand,” or perhaps an irritating heckler. If we see it in terms of convergence culture, however, the issues become slightly different. Cell phone and hand-held camera videos shot by audience members are more real than reality TV. They are perhaps what Mark Andrejevic suggested is part of a new culture of passive surveillance, but they are also sound and video bites that contain screams, cries for help, and a jaded audience of highly educated students and faculty. More importantly, they are interactive. Ten hours after the event, less than 75,000 people had watched it on YouTube. A day later the number had skyrocketed to over half a million, as it simultaneously appeared throughout the web and on mainstream television. Despite the media attention on the event, however, we must wonder: would Meyer’s arrest have been broadcast were it not for the people with cameras? Would it have been broadcast without YouTube? How would it have been framed and reframed by mainstream media outlets, cut or edited or played without sound? Would the story have become big if mainstream journalists were not terrified of having their stories scooped once again by a voracious crowd of technologically savvy individuals?

Convergence does not hail a new era of consensus, and we should not expect it to do so. In fact, we should be wary of such a thing, as Chantal Mouffe and others have reminded us. Instead, we should see Jenkins’ “convergence” as a new form of conflict, in which emergent media, as Raymond Williams suggested, creates and emphasizes locations and locutions of conflict that force dominant social and media systems to evolve. Compromise and consensus are not the same thing; politics and the political are not the same thing. Community based in conflict, with a devotion to sharing of information and perspectives outside of a political and media system that has increasingly shown itself to be myopic at best and untrustworthy at worst, has the potential to show us a reality beyond the framework of repression envisioned by the Frankfurt school. However, like any protest or activist movement, it is a potential for which we must fight, as students, as scholars, as citizens, and as a community.

Images

1. Andrew Meyer tased by police at a University of Florida political event

2. Protest on the Berkeley campus over a proposed athletic facility

3. Free speech protest at Berkeley in 1964

Please feel free to comment.

I have my doubts that the Andrew Meyer tasing would have generated any news coverage outside of local Florida news were it not for sites such as YouTube and blogs. Not to sound overly optimistic, but it does seem that much of Internet news is beginning to influence the kind of news stories that national mainstream television news is now having to cover. I don’t watch much TV so I don’t want to speak for all stations, but while getting my nightly fix of The Simpsons and King of the Hill on Fox, I have noticed a HUGE push for their news website. There are countless commercials urging the viewer to check out the Fox news website(although I’ve never actually checked it out). Recognizing that people are choosing to get much of their news online, are these companies responding by just trying to send us to their sites? And will that really make a difference? I speculate that most people who receive their news online are not relying on corporate media sites as their primary source. Can more conventional media really combat the viral effect of Internet news?

This article is timely, especially considering the widespread protests at Columbia University last week during Iranian President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad’s speech.

Interestingly, while some of these protests focused on rightfully contradicting Ahmadinejad’s views on gays and the Holocaust (he seemingly denies the existence of both), there were other protesters whose message consisted of wanting to muzzle or gag Ahmadinejad himself. I find it mightily ironic that public protesters–of all people–should engage in trying to stifle free speech, regardless of how hateful it might be.

After all, protest itself is nothing if not the act of free speech, even when those with signs and banners are consigned to “free speech zones” around Republican party conventions. How interesting that some campus protesters seem to have missed this point entirely.