You Haven’t Seen Avatar Yet

Charles R. Acland / Concordia University

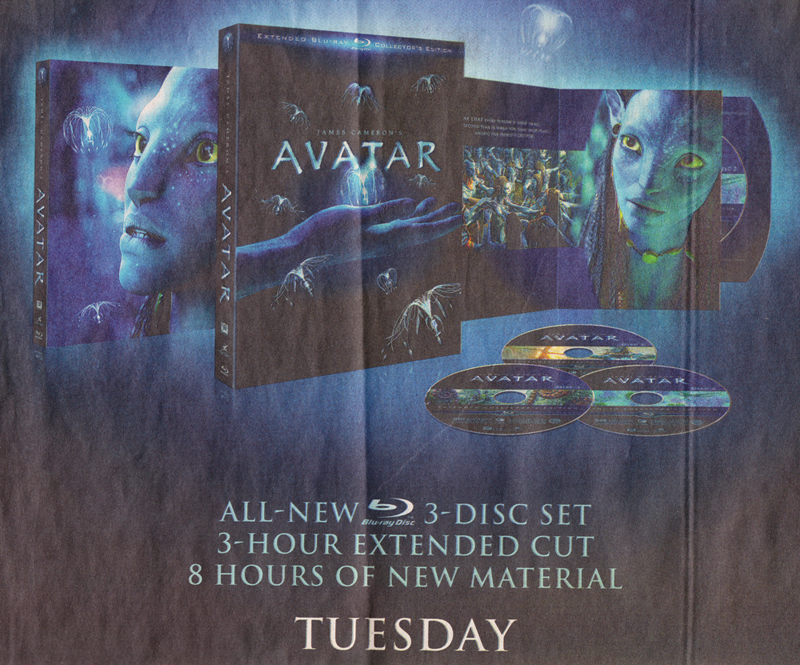

“Extend the journey.” That’s one of the taglines for Avatar’s second DVD/Blu-ray release (November 16, 2010). This journey isn’t just a reference to James Cameron’s sci-fi blockbuster. It describes the layers of packaging one must deal with to get to the actual DVDs inside: plastic wrapping, cardboard sleeve, hard cardboard cover, book-like bound folder, and finally pull-out tabs for each of the three discs. This object, with its luminescent blue color scheme and images of the film’s Na’vi creatures of Pandora—no live-action scenes here—is a jewel box designed to instil a sense of preciousness to an already amply familiar movie. For all the technological sophistication of compressed digital storage to be read by lasers, let’s remember the importance of folded cardboard in the augmentation of value.

The DVD release is one of many predictable stops on a journey through the iterative world of moving image commodities. Considering the most recent DVD edition of Avatar, “extend the journey” can also be seen as a description of the core business plan for a nascent film franchise, which requires additional films (with more Avatar installments reportedly coming December 2014 and December 2015) and exploitation of multiple merchandising opportunities. But a new film episode is only one way to expand a film saga; with this particular DVD release, we see that the movie itself is elastic. New chapters supplement the original work, such that what we think of as Avatar is in fact a mutable and varying entity, a work-in-progress.

Avatar is not a single finished film with defined boundaries. Though not officially the title, much advertising material refers to the movie as James Cameron’s Avatar, an auteurist conceit that carries the stamp of brand predictability. His name is a guarantor of a set of generic and technological expectations. Moreover, the titular presence of Cameron highlights the ongoing involvement of his creative hand. This is his film, and he will do with it what he wishes. Notably on the November 2010 DVD/Blu-ray release, the phrase “director’s cut” does not appear. Instead, this set is the “extended collector’s edition.” One can confidently assume that there will be a “director’s cut” at some point, meaning the textual variations are not yet finished. Most obviously, the currently available Avatar DVDs and Blu-rays do not offer the primary feature of the theatrical releases—3D—meaning more home viewing options are sure to follow.

The packaging promises that with the DVD we “journey deeper into Avatar”—not Cameron’s fictional universe but Avatar the film. In this way, the line hails us to engage more fully with the film as an industrial product rather than directly inviting us back to Pandora with the colonizing Earthlings. Similarly, the outermost sleeve asks us to “experience the complete filmmaker’s journey with 3 discs and 3 versions of the film!” This ambiguous statement presents the entire package as a making-of documentary, which it isn’t. Nonetheless, with three versions of the film included, among other offerings, this DVD set provides a highly selective window into an ongoing production process.

What are the three versions included in this edition? One is the original theatrical release from December 18, 2009 (162 minutes), and which had previously appeared as an unadorned DVD on Earth Day April 22, 2010 to capitalize on the film’s environmental ethos. In a perplexing marketing decision, indicative of the transition period between DVD and Blu-ray, a two-disc package of both formats was also released at that time, which was the only way one could purchase a Blu-ray version. The other two versions are the “special edition re-release,” in theatres on August 27, 2010 (170 minutes), and, exclusive to this set, the “collector’s extended cut” (178 minutes). So, by the third version, the film is now sixteen minutes longer than the original release. Considering the preference options we expect of DVDs, there are other demographically sensitive kinds of adaptability, too: Spanish and French audio tracks in addition to the original English, English and Spanish subtitles, closed captioning, and a family audio option that removes “objectionable language.”

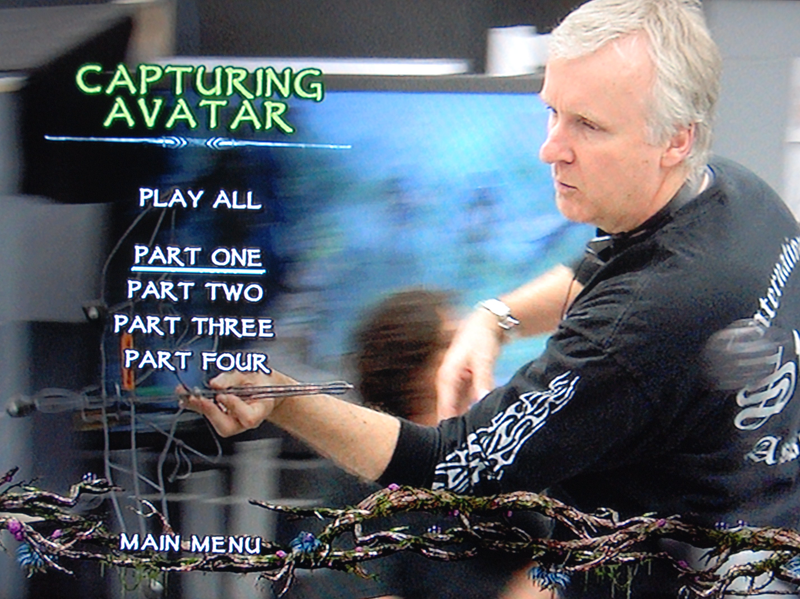

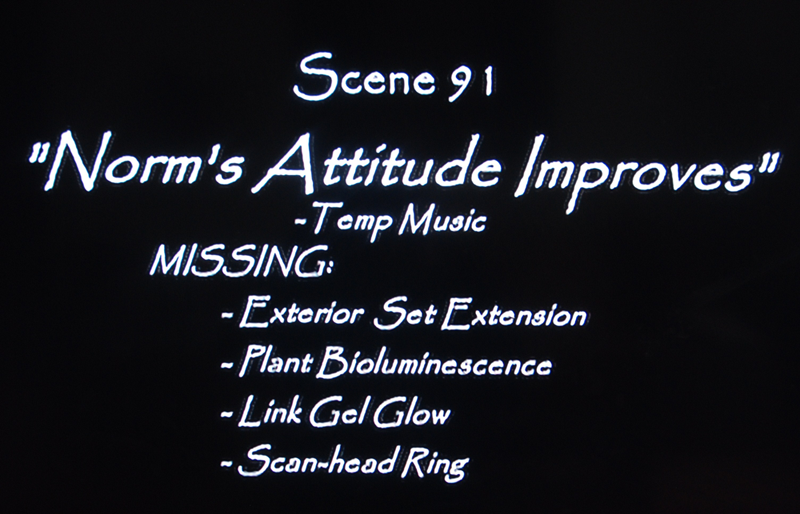

The three versions of Avatar are split across two discs. The second disc also includes A Message from Pandora (20 minutes), a documentary short that chronicles Cameron’s involvement with the environmentalist organization Amazon Watch, depicting actions taken against a massive Brazilian dam project, but which does so by establishing parallels between indigenous people of the Amazon and Pandora’s Na’vi. The third disc, called “Filmmakers’ Journey”—note the possessive generously acknowledging the collaborative nature of the enterprise—includes a making-of documentary, Capturing Avatar (98 minutes), as well as forty-five minutes of deleted scenes, that is, additional additional footage. These are not bloopers. They are scenes that are “never-before-seen” with “unfinished footage” in various stages of completion. In viewing, one can extrapolate the extra layers of construction needed to polish each clip—green screens filled in, performance capture footage fully rendered, and soundtrack finished. Still, the term “scene” suggests a degree of completeness, making these oddly legitimate parts of the film, or at least the filmmaking process, despite their lowly extra-narrative status. What will it take to move these from the hierarchically subordinate third disc to the body of the text? Or are they only ever to appear as adornment to the main feature, no matter how mutating and expansive it may be? Certainly, the status of a clip as “never-before-seen” ends the moment of release. The third disc also conveniently offers in a single location the sixteen minutes of additional scenes added to the main features. No need to wade through each entire version of the film in order to spot what’s new.

These clips amount to three hours of additional material in this DVD set. That’s nothing. The simultaneously-released Blu-ray format boasts eight hours of extras, including extensive behind-the-scenes production footage, an archive of production material, and interactive production information, some of which was live for a limited time.

What is this material we call “extra footage” and “deleted scenes” that have become conventional options on DVD/Blu-ray menus? They differ from other forms of extras in that they are explicitly supplements to the world of the film. If they appear with authorial validation, and are inserted into a film, the new and improved version supposedly becomes the more fully realized cinematic vision. Examples include such key moments in contemporary Hollywood as Steven Spielberg’s 1980 re-release of Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977), which includes footage inside the alien mothership at the end that did not appear in the first release, or of Ridley Scott’s 1992 re-release of Blade Runner (1982) as the director’s cut. A less successful effort, but one that marked the coming provisionality of digital cinema, was George Lucas’s digital insertion of creatures and scenes into the 1997 re-release of Star Wars: Episode IV—A New Hope (1977), which, obvious and distracting as they are, look like free rub-on transfers of dinosaurs from the bottom of a box of Sugar Crisps.

While these were all initially theatrical re-releases, as was Cameron’s first lengthened special edition of Avatar, the storage capacity of DVD and Blu-ray prompts even more ambitious expansions. DVD and Blu-ray allow us to buy footage in bulk. Fill the bucket to the brim, and whether you fill it with vinegar or wine is not as important as the sheer volume. The measure of this volume is minutes, and more minutes equal more value.

One template for DVD extras is Criterion’s cinephilic material of historical relevance to the artistic value of the main feature. Their edition of Breathless (1960) includes a booklet with the film’s original treatments, video essays, the original trailer, interviews with Godard and lead actors, and a making-of documentary. All these extras bolster the unique and stable work of Godard’s masterpiece, presenting it all the more assuredly as timeless. Even the transfer is approved by the film’s cinematographer Raoul Coutard, lest cinephiles worry about the digitization of a beloved classic.

But the Avatar model puts less stock in the singular prestige of the film. Instead, Cameron’s endlessly expanding imagination, as represented by the seemingly bottomless archive of filmed material and iterations, is the focus. And both home entertainment formats sell a peek into the production of the film that has resulted in this deep catalogue of footage, a peek that is largely attentive to the newest forms of cinema technology involved, including 3D shooting and performance capture. In this way, the expandable text is a romance with a particular mode of cultural production defined by an engagement with new technological materials and processes.

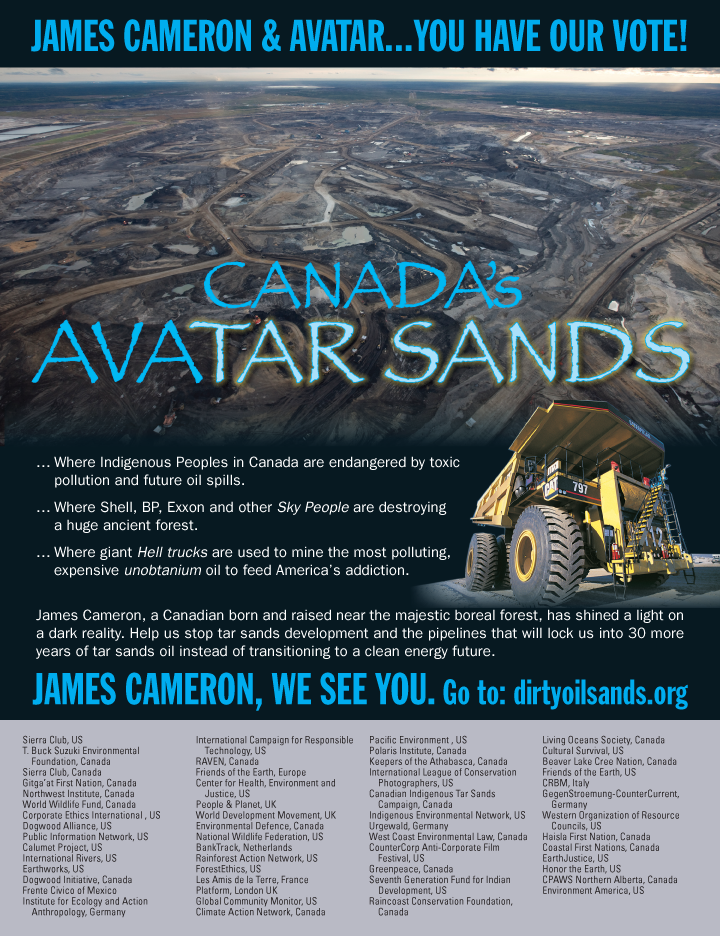

An activist spirit slips out of the film. For all of utterly conventional racial motifs, and its ideological limitations on other counts, Avatar is unambiguously a fable of exploitation and an explicit critique of colonial adventure. And as such, it has been mobilized by Palestinians to protest an Israeli barrier, who dressed, and inhaled tear gas, as the fictional Na’vi. Canadian and First Nations environmentalists used the popular tale to draw attention to the developing catastrophe of the Alberta oil sands projects, even placing a notice in Variety to voice support for Avatar’s best picture Oscar campaign. In response, Cameron subsequently toured the Northern Alberta site. He met with politicians and business leaders who themselves hoped to win Hollywood blessing for their enterprise. But Cameron did not disappoint the activists, and he has, to date, steadfastly condemned the energy project.

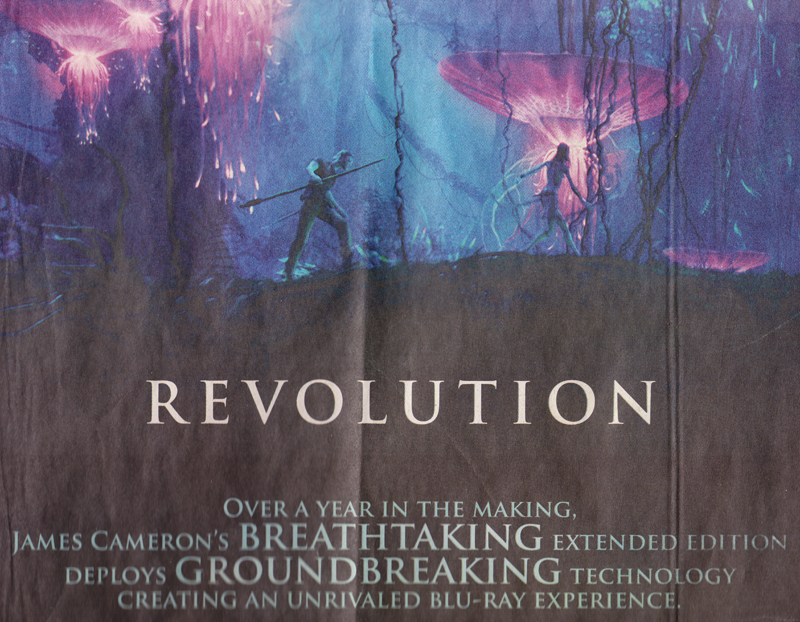

As a dominant theme in Avatar, and as evident in A Message from Pandora, political engagement has also served as a way to promote the film. Accordingly, newspaper advertising called the “extended collector’s edition” as a “revolution,” a term that simultaneously referred to the uprising depicted in the film, referenced earlier descriptions of Avatar’s innovative 3D filming processes, and described the work that went into the DVD/Blu-ray sets. Part of the November 2010 DVD re-release is a flyer for “an activist survival guide” book tie-in, which is “a confidential report on the biological and social history of Pandora.”

As energizing as the dream of revolution may be, what is actually at issue is a set of expectations about the importance of technological innovation in moving image industries. Avatar, with an ongoing re-release schedule that alternates between platforms and an expandable text and paratext, represents a refinement of franchise operations in the context of digital production and distribution. And the value of the new scenes added to a new Avatar iteration is beyond narrative extension, character elaboration, or thematic depth. Amassing more material to cram into the film, or to file away as a sidebar, marks a salient difference from previously available versions, thus warranting the additional release. But it is also evidence of the epic proportions of the production and the capability of digital manipulations of a text. In this way, the dominant topic of each re-release is a celebration of new technological processes and the expansiveness of the blockbuster economy itself.

Image Credits:

1. Detail, New York Times print advertisement, November 14, 2010.

2. DVD insert, Avatar Extended Collector’s Edition, Twentieth-Century Fox, 2010.

3. Screen capture of DVD menu, Avatar Extended Collector’s Edition, Twentieth-Century Fox, 2010.

4. Screen capture of DVD chapter, Avatar Extended Collector’s Edition, Twentieth-Century Fox, 2010.

5. www.dirtyoilsands.org

6. Detail, New York Times print advertisement, November 14, 2010.

Please feel free to comment.

Although I saw the movie Avatar, I wasn’t aware of the DVD release. Even considering that most DVDs have special features, it was surprising to know that there is so much packed into the Avatar! When you speak of new technological processes and the expansiveness of the blockbuster economies, I though about how far we have come from VHS to all these ‘special’ version DVDs. Technological process suddenly doesn’t seem all that great; it now seems to enable the blockbuster economoy to create for revenues for themselves.

It’s quite telling that the highest grossing film ever is by no means it’s most critically acclaimed, even by the common viewer. I remember after having sat through the film (an experience that was admittedly fun at the start, but was a struggle by the end) I left the theatre with an odd feeling: I didn’t really like Avatar, but I was “glad” that I had seen it. As the days went by, I tended to omit my feelings about the actual movie, and rather focused on the spectacle when talking to my friends. I found myself saying something to the effect of “it’s not bad, but you’ve got to see it”. The feat of making the film was enough, the actual content was almost inconsequential. It got to the point where fans and detractors seemed to speak of a “need” to see the film, as if it was some religious obligation that may or may not be enjoyable but certainly is necessary.

Avatar isn’t so much a film as it is an accomplishment like building a pyramid or a dam, and fans seem to care far more about mo-cap techniques, and 3D imaging than they do about the characters and their conflict. It’s as if the ad campaign can be distilled down to “we tried really hard and spent a lot of money, so you should like me”. The epic-ness of it all is what matters, and talk a sequel and a trilogy only served to bolster that claim. One could draw the comparison to dining out at a restaurant in America. The focus on quality shifted to a focus on portion size – bigger is better, and taste is secondary. The longer the film’s runtime, the more it cost to make, the longer it took to produce and the more sequels are in the pipeline, the more destined it is to be a masterpiece.

I completely agree with you on your assessment of Avatar’s deluge of bonus materials and rereleases. The only place I might have a point of disagreement is the notion of deleted scenes as representing a more realized cinematic vision of a filmmaker.

Home video/DVD/Blu-Ray extras, for the most part, are about promoting a film that the consumer has purchased. It is an irony, to be sure. Because considering that the film has already been purchased, one would think that there is no more need to promote the film. There really is not, but people want to feel as though they are getting something for the money they are paying. For all of the claims that these sets give us extended, exclusive, explosive, essential, enlightening, or other “e” described bonus material, more often than not, scope of extras is promoted as depth.

I do like that you mention the Criterion Collection, as they probably are the standard for what DVD extras ought to be, considering they claim to release “important classic and contemporary films.” Rarely are they producing DVDs of new releases (Wes Anderson’s films and Fincher’s The Curious Case of Benjamin Button are the two exceptions that come readily to mind). Their features are, as you write, “cinephilic material of historical relevance to the artistic value of the main feature” and supplement rather than overpower the main feature. The painstaking research and restoration for each film is evident in the high price of a Criterion DVD product which reflects a high level of quality if not necessarily quantity of extras.

A film like Avatar, on the other hand, has the highest unadjusted gross in film history, so it can be safely assumed that a great many people have already seen it. It is too recent and present to have features discussing historical relevance or artistic value. The only way to get the masses interested in such a thing repeatedly is to make them feel like they are getting more of what they already enjoyed. So, that leaves a discussion of the film’s readily apparent technological innovations and new versions of the film.

Rarely are extended versions of a film a greater realization of the film-maker’s artistic vision. More often than not, it is a ploy a resell a film that people have already seen. In the case of James Cameron, a few years ago I would be inclined to give him the benefit of the doubt. Both Aliens and The Abyss were finished and recut for “special edition” home videos after the studios tinkered with them. (That being said, I do recall him saying that the extended version of Terminator 2 is just an extension, not a director’s cut.) However, after Titanic and Avatar, Cameron is at a point in his career where he has almost complete control of his films and ideas. I’m skeptical of notion that anything less than his total vision was on screen the first time.

Terms like Extended Edition, Special Edition, and Director’s Cut are thrown around with such frequency today that it is difficult to divine their actual meanings anymore. Insertion into a film no longer means that there is authorial validation of the choice. You mention Ridley Scott and Blade Runner, and he’s a perfect example of this. The 1992 release of Blade Runner was billed as a Director’s Cut, but he himself did not have artistic control over the project, working through notes given to an editor. It was not until 2007’s “Final Cut” of Blade Runner that he worked on it to give a definitive authorial stamp on the film.

An extended edition of Gladiator was released to DVD several years ago, but Scott states in an introduction that the theatrical version is in fact the director’s cut. The “Extended Edition” is just to give fans of the film more of what they enjoyed (ie. to get them to pay for the movie again). Scott’s Kingdom of Heaven was given the Director’s Cut treatment, this time actually being a director’s cut, as he corrected what he viewed as studio mishandling of the film.

Scott also directed the original Alien, which was released as a “Director’s Cut,” which Scott personally worked on, several years ago. Yet he claimed, at the time, the term “Director’s Cut” is a misnomer for the re-release, since it is merely a recut version of the film that happens to include deleted material, while the original 1979 version remains his preferred cut of the film. In that case, “Director’s Cut” is a promotional distinction.

And, of course, I’m leaving out every extended edition that studios now seem to release on a weekly basis. That an alternate version of a film represents (or even has) a final authorial vision is the exception rather than the rule. Additional releases are rarely warranted, though studios would certainly like us to think so.