Why Political Journalists Should Get Into Top Gear

by: Stephen Harrington / Queensland University of Technology

For as long as I can remember, I have been crazy about cars. Researching into all of the obscure details and performance figures of the latest four-wheeled offerings from Europe’s top marques has long been an intense interest of mine. Unfortunately, like most deep fascinations, one of the defining features of being a car-nut is the feeling of isolation. Finding someone who has both the patience and knowledge to hold an extended conversation with me about cars almost always seemed like the social equivalent of striking gold in my own backyard. That sense of solitude, however, is starting to fade very rapidly – and for that I owe much gratitude to the BBC program Top Gear.

For those who have no idea what I am talking about, allow me a moment to explain. Top Gear has been around for many years as both a TV show (produced in the UK) and affiliated magazine. Over the past five years it has managed to develop what is a unique and highly successful formula by effectively re-casting itself as an entertainment show centred around car culture, rather than holding onto what was a niche appeal for outright enthusiasts like myself. The show (which is currently hosted by the somewhat self-righteous and highly-opinionated Jeremy Clarkson, James May and the recently recovered Richard Hammond) is still dedicated to cars – each program features a new car test of some sort, a celebrity interview, and several other one-off features – but it has managed to find something ‘new’ in a fairly tired formula.

Although Australia (where I live) can lay claim to a fairly robust car culture, car television in this country has almost chronically failed as a genre – if in fact it is a ‘genre’ – for reasons that are seemingly too numerous to get into here. Top Gear, however, is the first television show in many years to screen in prime-time, and seems to have genuinely sparked an interest in an otherwise car-weary Australian public. The reasons for this success, I enthusiastically argue, are that the show presents its rather specialized subject matter in a way that a much wider section of the general public can understand and, perhaps most importantly, enjoy. It is a generally unconventional approach to cars and therefore manages to appeal to a much more diverse audience than what it once did.

So, rather than explain how fast and nimble the Lotus Exige is, Clarkson showed how fast it can go by trying to evade missile-lock from an Apache helicopter flying overhead. Rather than discussing a Range Rover (a fairly sedate vehicle at the best of times) in terms of its technical ability to find traction on uneven surfaces, Clarkson simply had to try and hide from an army tank over a hill-strewn training ground. Instead of talking endlessly about the new Toyota Aygo’s maneuverability, the Top Gear crew instead decided to host a football (soccer) match using the cars – most of which were driven by stunt drivers in two teams – to punt a giant inflatable football around a bitumen pitch. Replete with collisions, spins, fouls, amazing driving skills and a last-gasp winning goal, I really cannot imagine a more engaging, exciting and fun way of reviewing a cheap, mass-produced (that is, ordinarily deathly-dull) city runabout.

Equally important to mention here too is the fact that Top Gear rarely assumes a high level of audience knowledge; the hosts seem acutely aware that they have a responsibility not only to audience knowledge, but also to audience interest. So if, for example, Richard Hammond mentions a horsepower figure, he usually makes some attempt to put that figure into perspective. Rather than talking about a car’s low level of torsional rigidity, Jeremy will instead explain how ‘floppy’ it feels, or at least offer some sort of easily-digestible analogy to explain why that trait is a problem in a sports car. On one occasion, rather than lecturing their audience about being cautious at level crossings, the Top Gear team instead decided to just go ahead and demonstrate their potential dangers by crashing a speeding train into a second-hand Renault Espace.[1] Sure, the stunt may have been executed primarily because it makes for spectacular viewing rather than for some genuine public safety purpose, but the idea that something can’t be both exciting and informative at the same time is surely one that has outlived its brief period of relevance.

Of course, one could argue that Top Gear represents nothing more than a diluted, lowest-common-denominator treatment of motoring – and, in many ways that claim has some purchase, although I would dare not argue that it should or could appeal to all tastes – but I genuinely think we should look past that to see that it is doing something very interesting. It is, perhaps for the first time, bringing cars to the people rather than trying desperately to do things the opposite way around. All together, this means that a fanatic such as myself can find this show very fascinating, but so too would someone who knows very little about cars and the car industry. As I noted earlier in this article, finding someone with whom I can have an extended conversation about, for instance, my ‘dream garage’ – that is, what cars you would go out and buy with $1 million – was always next to impossible, but I now find myself having these kinds of conversation at the most unlikely times with the most unlikely of people. It really is amazing to think that a large number of people (certainly many more than I can remember) now understand why a Mercedes CLS55 is far more exciting than an Audi S6, realise what the ‘power’ button in a BMW M5 does to its engine, or know how many cylinders and turbochargers a Bugatti Veyron is endowed with (16 and four respectively, if you’re asking). Similar to what MythBusters has done for scientific inquiry, Top Gear proves that dreary subjects can actually resonate far better with the viewing public when they are approached in unconventional ways.

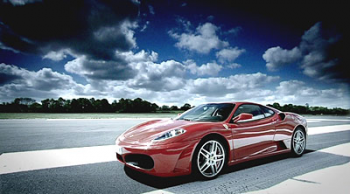

As a media researcher and someone who has seen first-hand the effect Top Gear has had on my fellow Australians, all of this makes me question weather this show’s ethos could translate into other domains. I wonder: would it be possible to apply the Top Gear ‘attitude’ to the world of Politics? Could the legions of TV journalists who deal in a subject that so many people find sleep-inducing learn a few lessons from this program? Of course, even as I write this I am all too conscious of just how crazy a concept that would seem, but I don’t think that it is entirely out of the realms of possibility. Sure, it may be hard to compare politicians themselves to the ‘sex-appeal’ of a Ferrari F430 going flat-out on a race circuit, but I am fairly sure there were people who once said that TV shows about cars could never appeal to ‘the masses’ either.

Perhaps Michael Moore[2] was thinking along similar lines when he offered the following anecdote in his much-derided and much-lauded book, Stupid White Men:

“I once heard the linguist and political writer Noam Chomsky say that if you want proof that the American people aren’t stupid, just turn on any sports talk radio show and listen to the incredible retention of facts. It is amazing – and it’s proof that the American mind is alive and well. It just isn’t challenged with anything interesting or exciting. Our challenge, Chomsky said, was to find a way to make politics as gripping and engaging as sports. When we do that, watch how Americans will do nothing but talk about who did what to whom at the WTO.”[3]

Of course, I am not sure what a political TV show inspired by Top Gear would do or look like exactly, but this really is not the central concern of my argument here – the more fundamental question is over who exactly might watch such a show. Because I am just as much of a political junkie as a car-nut, I am sure that I would be among the first to tune in, but so too, I suspect, would a whole bunch of people who currently care as much for political television as they once did for shows about cars.

Notes:

[1] This show has recently developed a fascination for doing strange things to used cars. This may have reached its zenith recently when a Reliant Robin was attached to a giant (amateur-built) rocket in an attempt to mimic the Space Shuttle.

[2] Michael Moore himself has already treated politics in new and interesting ways (in, for example, his TV show The Awful Truth, or his film Fahrenheit 9/11), though I wonder if his polarising nature may be equally problematic – that he may be ‘preaching to the converted’, as it were. Perhaps the readers of Flow might like to offer their own opinions on this matter.

[3] Moore, Michael (2001) Stupid White Men. London: Penguin, p. 86.

Image Credits:

1. Top Gear, series 1, episode 7

3. Top Gear, series 6, episode 1

4. Top Gear, series 9, episode 5

5. Top Gear, series 6, episide 8

Please feel free to comment.

This column comes at a timely moment for me, having just returned from a large convention of political activists, all of whom are as obsessed with Senate votes and campaign contributions as car-nuts must be with carburetor performance statistics. I think Stephen may be on to something here, but the question remains how to make politics as sexy as sportscars without simply repeating the existing news formats already on TV.

Arguably, political journalism has been slacking over the past decade or so, which has created space for the blogs and alternative media to become more prominent in terms of hard-core news reporting. Thus, there is still an outlet for junkies desperate to know every last detail. However, translating that into something that the mainstream can be riveted with is certainly a challenge.

What I find most intriguing is that since politics plays such a critical role in everyone’s daily life, why isn’t it as fascinating as baseball or car chases? Why is it considered “boring” or worse? Is it just considered too much of a “downer?”

that realy good show