Fairly Normal Activity: Horror and the Static Camera

Janani Subramanian/ University of Southern California

I saw both Paranormal Activity 1 and 2 with my 19-year-old Indian-American brother and 60-year-old Indian father. We were a motley crew of generations, education, and general outlooks on life, but we were all huddled in our seats, hands over eyes, at various points in both films. At some point after the first film, my brother (the same one who jumped in his seat during the film) scoffed that nothing really happened in the film, and after the second film, my dad joked that he was going to make a movie called Normal Activity where he just hangs out in the kitchen. Both comments made me think about the curious experience of watching these two horror films that were based on a great deal of waiting and watching, a viewing experience fairly rare in mainstream, effects-driven horror films.

Most press about the first Paranormal Activity (PA) focused on its low-budget production and high-grossing profits, relatively unknown writer/director Oren Peli, Steven Spielberg’s involvement with distribution, and the film’s viral marketing campaign.1 The second film, while not as well-received as the first, kept Oren Peli as a producer and attempted to provide both backstory and continuation to the first film’s storyline. In keeping with the primarily Internet-based marketing of the first film, Paramount—who owned the rights to the film after acquiring DreamWorks in 2005—featured a trailer on its website with mysterious “Easter Eggs” that the diligent fan could discover by playing the trailer backwards.2 The plethora of press surrounding the film’s marketing, distribution and exhibition, rather than the content of the film itself, is reminiscent of its found-footage horror predecessor, The Blair Witch Project.

The Blair Witch Project shifted paradigms of film marketing, independent filmmaking, and the generic conventions of horror. Marketing started through various websites that claimed that the film’s story was true, while the filmmakers refused to confirm or deny these theories, and by the time of its release, the film had “already acquired a cult status and was guaranteed an audience when it finally opened nationwide.”3 The film’s use of documentary aesthetics—the improvised dialogue of the characters and the shaky camcorder visuals—has been discussed extensively within scholarly discourses, along with the self-reflexivity of using student filmmakers as the main protagonists.4 Working within the traditions of the amateur, found-footage mockumentary, PA creates a similarly chilling movie experience as a young couple tries to document the paranormal presence that has supposedly invaded their home.

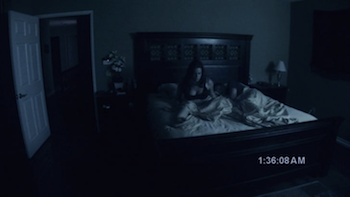

What sets PA 1 and 2 apart from the found-footage genre of The Blair Witch Project and the more recent Rec (2007) and The Last Exorcism (2010) is that the couple and family in each film are not trying to create a documentary, but merely trying to understand what is happening to them. In the first film, Micah Sloat and Katie Featherstone (the actors’ and characters’ names) set up a camcorder in their bedroom to try to capture inexplicable activity that goes on while they sleep. The majority of the film is seen from the perspective of the camcorder in the corner of the bedroom, where hours of footage of the couple sleeping is fast-forwarded to the specific points where activity occurs.5 I would argue that there are quite a few elements that make these scenes suspenseful—for one, sleeping is an intensely intimate and mysterious human activity, and the hours of footage of the couple’s inactivity, except for changing sleeping positions, is already marked by an eeriness of witnessing humans at their most vulnerable. The bluish hues of night footage cast the scene in a monochromatic surreality, and, most interestingly, the static camera encourages a different kind of viewing experience. The shaky camcorder of Blair Witch and its ilk creates a sense of suspense just by the fact that the camera is being guided by a human, and therefore vulnerable, hand, while the static camera, I would argue, is marked by a kind of cold, mechanical invulnerability. Unlike the documentary crews and camera-people who are invested in other films’ unfolding of events, from alien attacks (Cloverfield) to zombies (Rec/Quarantine) to possession (The Last Exorcism), neither PA 1 nor 2 ends because the hand guiding the camera gets blown-up/eaten/chopped off; the films end when the tape runs out, when the camcorder falls off the stand, or, in the case of PA 2, when the security camera is destroyed. Our investment as viewers lies only with the technological apparatus that allows us to watch these events unfold, and the distance between the technology and human activity removes any illusion of control we might have over the film’s narrative; the camera’s cruel indifference makes what is happening that much more horrific.

The second film in the franchise emphasizes the static nature of the camera to a greater extent, as the film’s events are seen from the different perspectives of security cameras located throughout this family’s house.6 To me, the second film was even more interesting to watch than the first, because “watching” for a large portion of the film consisted of staring at empty rooms. Without human bodies to focus on, I found myself scouring the screen for out of the ordinary movement of objects or changes in the environment. During the majority of these scenes, the audience not only giggled or called out to the screen out of nervous anticipation, but also because there was something absurd about all of us sitting and staring at a family’s house where nothing was happening. My favorite moment in the film was when the family’s automated pool cleaner keeps mysteriously crawling out of the pool; while the filmmakers used it to toy with us and set us up for the more terrifying events in the film, I also considered it tongue-in-cheek representation of the true horrors of suburban domesticity—having out of control appliances disturb a comfortable and privileged existence.

Each film’s representations of domesticity, femininity and the demonic demand a closer inspection in the context of generic histories of both horror and the demonic, but for my purposes, I would be interested in exploring more connections between the static camera and the viewing experience in horror films. The static camera and the extremely long take have been theorized in avant-garde cinema, most famously in relation to Michael Snow’s 1966 film Wavelength, a 45-minute slow zoom into an apartment where very little happens. The challenges of watching the film (and of screening it in classrooms7 )—of contemplating an unchanging space for an extended period of time—are what critics have celebrated as Snow’s revelation of the “essence of cinema” and the viewing experience.8 I am not suggesting in any way that PA 1 or 2 is an avant-garde film or incorporates avant-garde aesthetics, but rather raising questions about the effects of the static camera and unchanging mise-en-scenes on the horror genre and on the viewing experience.

Image Credits:

1. Something Disturbs Katie Featherstone in Paranormal Activity 1

2. The Nursery in Paranormal Activity 2

3. The Kitchen in PA 2

4. Errant Pool Cleaner in PA 2

Please feel free to comment.

- See http://articles.latimes.com/2009/sep/20/entertainment/ca-paranormal20, http://latimesblogs.latimes.com/entertainmentnewsbuzz/2009/09/paranormal-activity-expanding-after-selling-out-nearly-all-midnight-shows.html. [↩]

- http://www.paranormalmovie.com/index.php. [↩]

- Jane Roscoe, “The Blair Witch Project,” Jump Cut, 43 (July 2000): 3-8. http://www.ejumpcut.org/archive/onlinessays/JC43folder/BlairWitch.html. [↩]

- See Craig Hight and Jane Roscoe, Faking It: Mock-Documentary and the Subversion of Factuality (Manchester University Press, 2002) and Jeffrey Andrew Weinstock, Nothing That is: Millennial Cinema and The Blair Witch Controversies (Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 2004). [↩]

- Ingeniously parodied in 30 Rock episode “Verna,” where a camcorder captures Liz Lemon sleep-eating. [↩]

- There is a connection to the first PA – this is Katie Featherstone’s sister’s house, and the events we see precede those of the first film. The filmmakers have tried to establish a mythology about why a demonic presence is targeting these sisters, which will probably be the basis of the recently announced third installment in the franchise. [↩]

- See Michael Zyrd, “Avant-Garde Films: Teaching Wavelength.” Cinema Journal 47. 1 (Fall 2007): 109-112. [↩]

- Gene Youngblood, Expanded Cinema (New York: P. Dutton & Co, 1970). [↩]

Great article. I think you’re keying into a very interesting linkage between technology and horror. In a similar vein, I’m curious about the effects–both intended and not–of the body-mounted cameras that were used in MTV’s Fear in the early 2000s. Since that show, I’ve seen them used in a few other shows, most recently True Blood during a V-trip that took a turn towards horrific. This camera set up maintains a static image of the body instead of the static image of the environment you describe, but there are similar amounts of wading through the mundane in anticipation of the moment of horror or surprise. The hand behind the camera is not vulnerable because there is no hand behind it, but there is a vulnerable body in front of the camera at all times, confronting the audience. Do you have any thoughts on this technique?