“I was marrying sisters … that was my choice:” Big Love, Post-Feminist Choice, Scripted Lives and Judging Women

by: Kim Akass and Janet McCabe / Manchester Metropolitan University

Are the Henrickson sister-wives – Barb, Nicki and Margene – from HBO’s original drama Big Love truly breaking new representational ground, contributing to a vibrant conversation on the state of contemporary feminism, or merely recycling old stereotypes under new guises? Wife number one Barb was born into a traditional Mormon family marrying Bill Henrickson straight after university and bearing him three children. After being diagnosed with cancer followed by a radical hysterectomy, she chose, along with her husband, to invite Nicki to be his second wife. (A decision placing considerable strain on relations with her mother and sister, both active in the Mormon Church.) Wife number two may judge harshly the valueless secular world she lives in, but nonetheless incurs huge credit card debt filling a void in her life that faith cannot address. And wife number three may find comfort in a sense of family absent in her childhood, but somehow thought she was only marrying Bill. Overcome at daughter Teenie’s baptism (the youngest child of Bill and Barb) Margene jumps in the pool pledging herself to the family: “I was marrying sisters, my sisters, that was my choice, and I’d make that choice all over again” (‘The Baptism’, 1: 10).

Mixed feelings, complicated sleeping rosters, the deception of respectable society in order to keep up appearances; and the choices and actions of the sister-wives, seemingly at odds with feminism, baffling to most, push us into new directions in the post-feminist age.

The Henrickson sister-wives probably feel they have no need of feminism. Does not, in fact, being content to stay at home raising children, in the service of God and their husband, give representation to the ideal of American womanhood that the media works so hard to promote (Faludi, 1992)? Given that America has recently been in the throes of a seismic political and religious shift to the right, shaped by the rise to prominence of the fundamental Christian Right with its pro-life, pro-family, anti-gay agenda, Barb and Nicki at least are well rehearsed in its rhetoric. At the moment of baptism when Margene pledges herself to her sister-wives, insisting that it is her choice, and co-opting a liberal feminist rhetoric to do so, she finally accepts what being a sister-wife really means. In many ways Margene finds feminine salvation through religious fundamentalism and polygamy. Personal redemption wrapped up in religious rhetoric. But in an HBO twist she doesn’t pledge herself to the patriarch but to her sisters to help her find the way.

To their suburban community the Henrickson women appear unremarkable. Barb is married to Bill, and both Nicki and Margene are single parents who just happen to live next door. But behind the respectable veneer of three adjacent homes is a common backyard through which Bill can move unobserved between the three women’s beds.

Leslie Heywood and Jennifer Drake contest that “living up to images of success requires keeping secrets” (2003: 41). Who but the Henrickson sister-wives know more about keeping up appearances, bearing the heavy burden of family secrets? (Well, maybe Carmela Soprano.) Heavily invested in living the ideal as respectable citizens and mothers requires them to deny what such an image is built on – bigamy and the shifting sands of moral relativism. But given that this is television and that the longer serial narrative arc, to quote Michel Foucault, “imposes meticulous rules of self-examination” (1998: 19) disclosure is inevitable. Operating within a longer television serial form, subject to its particular narrative mechanisms, it is hard to keep secrets.

Considering Barb has long been “invested in the work of keeping silent, shoring up images and narratives that [she thinks] help [her] survive” (Heywood and Drake 2003: 41) it is not too surprising that her head gets turned by the Mother of the Year award. Surviving cancer, working as a substitute teacher, doing good works in the community and for her church, and bringing up children are enough to get her nominated by Teenie. And, after all, hasn’t she sacrificed enough for her family – her womb, her marital bed, her place on the roster when another wife is fertile, her affair with Bill. At first she accepts Nicki’s reasoning that she cannot possibly accept the nomination because, as her sister-wife points out: they all bring up the children and Barb’s re-entry into the work force would have been impossible without the others keeping the home fires burning. But when a photographer from the local paper arrives to take a family portrait, she does nothing to send him away (‘Where There’s A Will’, 1: 11). At first she pretends to have forgotten about the appointment, but then assembles her three children in the dining room, closing off the kitchen so no one can see behind the façade. Nicki and her children gatecrash nonetheless and Barb introduces her as a neighbour. One of Nicki’s sons asks if they are all going to be in the picture but the photographer tells him that this is just for family. Barb says nothing. She does not want to pull out. As she later confesses to Nicki she realises that it is important for her to be publicly recognised as a good mother.

Barb makes it to the final (‘The Ceremony’, 1: 12), but is disqualified when confronted with her polygamy. Fighting back tears, she confesses. Forced to walk from the competition, in front of the entire community, is a truly excruciating moment. But the aching disappointment, the pain of her dilemma, goes to the very heart of living the approved script. Believing that she might, could even, get away with the deception reveals the messiness involved in keeping the boundaries that hold her sense of self in place; to inhabit the image of feminine perfection means silence must shroud anything that falls outside this privileged representation. And here lies the rub. Barb is committed to working with contradiction and inconsistency in order to ‘collude with the approved script’ (ibid) from which she gains most pleasure. But it is a calculated risk. “I got what I deserved”, admits a crestfallen Barb. Her sister-wives have no consoling words, only silent tears.

But judging and being judged goes to the very heart of the feminine politics of Big Love.

On the surface it may seem that what is at stake in Big Love are male property rights, to women and everything else. But, as the conflicts deepen and the plot thickens, the contradictions and paradoxes of the women’s lives are made visible less through their relationships with men than in and through their relationships with each other and other women. For example, it is Wendy, Bill’s employee, who exposes Barb, disgusted by the practise of polygamy and its degradation of women; it is the First Lady, the governor’s wife, who shakes her head at Barb in disbelief, uttering, “Good Heavens,” on hearing the news of Barb’s polygamist lifestyle; and it is Nicki, the one who frets most about the family’s moral course, who judges Barb most harshly for vanity and risking exposure while at the same time sharing and knowing only too well her desire for recognition as a good mother and virtuous wife. Indeed the poignancy of Nicki’s words, “Barb, what have you done,” judging her, policing her, while sharing tears, supporting her, loving her too much. And it is, for us, this kind of complex feminine censure that makes Big Love so compelling.

Astrid Henry in her 2004 study of third wave feminism Not My Mother’s Sister identifies how generational conflict, the battle-lines drawn between mother and daughter, shapes feminist thinking and pushes forward the discourse. She persuasively argues that each new generation advances its own radicalism, and advocates its own unique position by denouncing others. Second-wave feminists vilify their fifties housewife mothers, postfeminists reject the radicalism of the second-wave; then along come the third wavers, raised on the promise of feminist equality.

At the heart of this discord, for Henry at least, is what she terms, “dis-identification,” an identification against something. Based on the work of Diana Fuss, and building on the theories of Judith Butler, this idea of refused identification, she argues, means that it is only by refusing to identify with earlier feminisms that the latest wave can create one of their own. It seems to us that rooted in any feminine discourse, feminist or otherwise, is regulation, a policing of women’s theoretical endeavours, of their behaviours, their sexual pleasures and their lifestyle choices. And it is this regulation through dis-identification that makes visible the nuanced, often poignant, dilemmas of these very modern women living in a quiet suburb of Salt Lake City as they set about policing themselves and each other.

Power relations are indeed complex. In the patriarchal world par excellence of a fundamentalist church where women are unlikely to have much say, or even be considered important enough to matter beyond providing domestic support, the sister-wives have long understood the formidable power embedded in roles to which no one pays much attention. They take great pains to be seen playing by the rules, operating inside meticulous codes – of marriage to powerful patriarchs, of motherhood extolled by media rhetoric, of family valorised and sanctified by religion. It is a lesson in unseen power whereby the wife and mother quite literally lay down the law; she is privileged, she is privilege. No wonder the policing process is so complex as the sister-wives jostle for power and influence. It pitches younger women against older women, mothers against daughters, new wives against first wives and one set of family values against another.

Contradiction is inherent in the uneasy choices that these women must make in order to live the life they choose; it is in their perplexing decision-making, in their complicated morality, in their competing desires, in their holding fast to scripted fantasies of heterosexual romance that feminism warns us about, in their being aroused by politically incorrect erotic pleasures, in their reproducing sexism and sexist stereotypes, sometimes even in their collusion with those who oppress other women – and in our complex emotional investment in them. In this sense, Big Love gives representation to our complex age of troubled emancipation. Steering clear of feminist agendas, but valuing individuality, these women have much to tell us about the contradictions we live with.

Citations:

Faludi, Susan. 1992. Backlash: The Undeclared War Against Women. London: Vintage.

Foucault, Michel. 1998. The Will to Knowledge. The History of Sexuality. 1. trans. Robert Hurley. London: Penguin.

Henry, Astrid. 2004. Not My Mother’s Sister: Generational Conflict and Third-Wave Feminism. Indiana: Indiana University Press.

Heywood, Leslie and Drake, Jennifer. 2003. “We Learn America like a Script: Activism in the Third Wave; or, Enough Phantoms of Nothing.” Third Wave Agenda: Being Feminist, Doing Feminism. Eds. Heywood and Drake. University of Minnesota Press. 40-54.

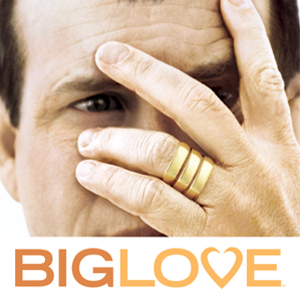

Images:

1. Big Love

2. The Sister-Wives of Big Love

Feel free to comment.

Indeed, it is important to learn to discuss issues such, as a polygamy, without resorting to caricatures and stigmatization.

I enjoyed your article. One correcion, though: It was Roman, learning about the nomination from Rhonda, who exposed Barb and the Henricksons as polygamists, not Wendy. This revelation is important for a number of reasons that play themselves out with the characters.

An interesting and timely read, as some of these issues have become much more apparent to me in this latest season. The relationship between the women is complex, but so too are their relationships with the women who still live on the compound. Nonetheless, it is fascinating to watch, as more people come into the fold and learn about them, not only how the sister wives negotiate such fragile terrain, but also how they emerge as such strong women from a seemingly victimized position.

I was particularly taken with a recent exchange two episodes ago, when Margene interferes with Bill’s (possible) courting of a fourth wife. Bill says to her, it’s not her place to get involved, at least not before he has made a decision, but she turns that around on him and argues that it’s not just him, but all of the women, who are entering into this decision. For me, this was an interesting, somewhat feminist spin on a very partiarchal religion – by injecting herself, and the sister wives, into the discussion, she enabled a vision of polygamy from the female perspective, which I found rather empowering and compelling.

As well, this week’s episode also revealed just how useless and powerless Bill is in some ways, at least within the domestic realm, as he could barely keep it together while Barb was away for the night. The character of Bill is interesting too, as he tries to negotiate his own masculine position as a polygamist husband and father that is similar too, but consciously different from, the male role models he grew up with, namely his awful father and Roman.

Two comments to add here. First, a small nuance that has large implications. It appeared to me from the first season that Bill and Barb didn’t freely choose to marry Nicki. Nicki’s brother Alby tells her in episode 5 that Bill married Nicki to get a loan from Roman (presumably to pay medical bills during Barb’s illness). It’s unclear whether he’s telling the truth, but in the 1st season I got the sense that Bill went into polygamy reluctantly and only later convinced himself it was for religious reasons.

I also think that the discourse of masculinity deserves equal attention in this article. The cult/compound’s tradition of following a single male prophet who assigns wives and kicks out younger men viewed as threatening is emasculating. We rarely see strong male characters at the compound, besides Roman, and even he only retains power through blackmail and tenuous religious devotion. Between the power of the compound leadership and the combined will of sister wives, men have very little power there.

Even the power we can expect for a man like Bill–i.e. the chance to have sex with multiple women–is weakened in Bill’s household because his wives choose who he sleeps with and when, and because he isn’t virile enough to satisfy all three women.

Everyone can go on analysing but the fact of the matter (and this is portrayed clearly in the show) is that Bill (the “patriarch”) is just a manipulating cut throat business man. Its all about the money and the sex (which the youngest wife clearly is for). Hbo is doing wrong by painting a too pretty picture of a polygamist household. Not enough women will read between the lines and see what character sarah says in the 2nd season to her mother that they are hardly different from the abusive compound and that She (her mother) is MADE to do exactly what other women have to “settle for less”. Its unfortunate to see a character like Barb who clearly has a mind of her own, submitting to her selfish husbands desires. I dont care what anyone thinks an old man marrying a girl young enough to be his son (as in bills case). its disgusting and thousands of steps backwards for every one of us.Unfortunately this is becoming more and more common place. We are losing the battle for equal respect for women in the facade of exploiting womens sexuality. There is nothing empowering about Margenes decision. She is a stupid child who was looking to be taken care of. We have too many women like this in the world who dont want to take responsibility for themselves and GLADLY give up their rights to a man.