Betty’s Back? Remembering the Relevance of the Rerun in the Age of Social Media

Dan Faltesek / University of Iowa

In May 2010, Betty White hosted Saturday Night Live to much media fanfare, and major media outlets from the Christian Science Monitor to CNN were quick to report the return of Ms. White to the limelight of network television. According to several reports, this was the result of the creative power of new media, most notably the social network Facebook. Reporters had found the well-circulated fan page “Betty White to host SNL,” which boasted tens of thousands of members, and was growing from a niche joke to a mainstream phenomenon as media reports of it’s existence abounded. This Facebook “movement” then became a key piece of evidence of the power of social media to reinvigorate celebrity once Saturday Night Live recruited the 88-year-old actress to host a show. According to this well-publicized story, Facebook had taken Betty White from the vault of television history back to the pages of Variety.

But is this really the whole story?

As convenient as this narrative frame is to explain the return of Betty White, it fails to account for the ways in which she was continuously circulated and recirculated between divergent publics over the past several decades. Betty White’s continuing presence is really a story about the importance of television reruns, not a story about the Promethean potential of social networks.

Betty White as a Social Media Figure?

Betty White is best known for her role as Rose Nylund on the hit 1980s sitcom, The Golden Girls, which ran from 1985-1992. Produced by Touchstone, and airing on NBC, The Golden Girls is a classic example of the multi-camera situation comedies of the late 1980s. The majority of the action took place on just a few sets, with an ensemble cast that starred four eclectic women. Rose was a happy, polite, somewhat naïve character in contrast to the stern Dorothy (Bea Arthur), man crazed Blanche (Rue McLanahan), and sharp-witted Sofia (Estelle Getty). Rose provided a character that was infinitely likable, compassionate, and interested in the lives of her friends. The women were able to converse about issues of sexuality and aging without any trepidation, which made The Golden Girls a breath of fresh, clean air in the all too often stale world of situation comedy. Although there was a short lived spin-off, The Golden Palace, the group left broadcast television for good in the spring of 1993.

After leaving the air, The Golden Girls moved onto the cable system, and from 1997 up until today, airs exclusively on Lifetime. Once a program has moved into cable syndication, repetition is the name of the game. Derek Kompare has argued that reruns are the lifeblood of American television, providing content that is both proven to resonate with audiences while filling time.1 Once a show makes the move into syndication, first run production costs are now likely paid down, production risks eliminated, and the brand position of the program is stable. By moving into an everyday appointment with television viewers, The Golden Girls became part of that great collection of rerun content that provides a common reference point to a multitude of viewers.

Televisual Counterpublics

The Golden Girls was effectively recirculated to niche audiences years before the viability of online video or DVD box sets. Syndication on Lifetime did more than simply providing an afterlife for an extremely popular broadcast program, it allowed counterpublics to repurpose it. To wit: The articulation of The Golden Girls with the LGBT community has appeared in several forms, such as in celebrations like Jim Colucci ‘s The Q Guide to the Golden Girls.2 Colucci’s book details the ways in which The Golden Girls resonates with an LGBT counterpublic. Through numerous textual choices and by embracing gay writers, The Golden Girls was prime for rearticulation — starting with the inclusion of the gay housekeeper Coco in the first episode, an episode where Rose faced the prospect of contracting HIV, and numerous episodes with gay and lesbian characters. By circulating both through primetime television with largely undifferentiated audiences and later through syndication with reception for niche audiences, The Golden Girls, and thus Betty White, remained in circulation continuously.

The identity and social meaning of The Golden Girls has been in flux, changing and growing with the modes of circulation that have delivered them. The Golden Girls have enjoyed a long career as an intertextual touchstone for programs like Sex and the City. Individually, Betty White has appeared and continues to appear on many television shows, including Boston Legal, The Bold and the Beautiful, and the new TV Land property Hot in Cleveland. In this sense, Betty White never went away.

However, the alleged resurgence of Betty White has not been through the reemergence of her 1980s character Rose Nylund, but through her performance of being Betty White who played the character Rose Nylund. In other words, the characterization that comes through in her current performances is neither her The Mary Tyler Moore Show character, Sue Ann Nivens, nor the Betty White of the 1950s variety hour. Consider her appearance on Saturday Night Live: the driving punch line behind her jokes was Rose’s now infamous frank speech. White’s June interview with Joy Behar is also revealing, as the takeaway from the interview for most news sources was the apparent outing of Cary Grant. Reflecting on decades of experiences, White has a unique ability to speak directly to what would be difficult questions. This form of direct talk about sexual issues was a core part of the appeal of The Golden Girls to their publics and continues to frame Betty White’s star text today.

The most important part of the recent history of Betty White in this perspective is not flashy digital media, but relatively old-fashioned media. Ron Greene has termed these forms of circulation “postal service” mechanisms.3 Postal service systems deliver texts to publics, they add to them by attaching them to other texts, and they deliver them cheaply. In the context of a television program, the postal service both delivers the content to the viewer, and modifies it through organization and presentation in context, what Raymond Williams would call, flow. The Golden Girls and Betty White have been delivered to their publics for years via television reruns and thus, this factor can’t be ignored in the rush to present Betty White as the latest Facebook darling.

[youtube]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IcFAMG8cOWg[/youtube]

Nevertheless, the Rerun Remains

Although it might be comforting to imagine a network of counterpublics autonomously creating texts that circulate by their own inertia, the texts that get the furthest still come from large, central, distributors. The public in the case of Betty White was clearly in the first and the last instance a major outlet of broadcast television. The yardstick for her success (and her return) was always broadcast television circulation. Becoming a liminal figure that crossed between publics and counterpublics was indeed possible because a dominant channel introduced her in the first place.

The case of Betty White reveals the continuing relevance of television to circulate meanings between what would be diffuse publics and counterpublics. Post-network television retains some vision of the “postal service”– even if this service is smaller and more efficient, the public-forming possibilities of television viewership remain in a digital era. In short, the story of the continuing popularity of Betty White is not a tale of novel technology, but of repetition. This is significant, as the figure of Betty White has evolved through the years to incorporate the best features of the characters she played. The story of an octogenarian who can instigate frank discussions of sexuality, and who has circulated through mainstream and the LGBT media is in itself a noteworthy start text. Retelling the story of Betty White as an instance of the triumph of Facebook ignores the political possibilities of reruns in the service of a far less important story — the existence of social networks. While mainstream reportage may emphasize our relationship with fresh, exiting new media, our love affair with the television rerun remains.

Image Credits:

1. Betty White’s “comeback”?

2. The cast of The Golden Girls.

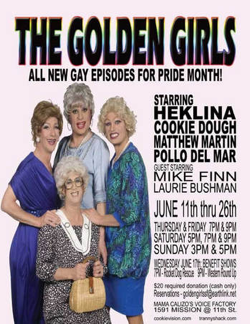

3. The Golden Girls meet Pride.

Please feel free to comment.

- Kompare, Derek. Rerun Nation. New York: Routledge, 2004. [↩]

- Colucci, Jim. The Q Guide to The Golden Girls. New York: Alison Books, 2006. [↩]

- Greene, Ronald. “Rhetorical Pedagogy as a Postal System; Circulating Subjects through Michael Warner’s “Publics and Counterpublics.” Quarterly Journal of Speech, 88:4. (2002): 434-443. [↩]