Welcome to Wrexham and Representations of Management in Football (Soccer) as a Product of the “Media Sports Cultural Complex”

Dr. Andrew Stubbs-Lacy / University of Staffordshire

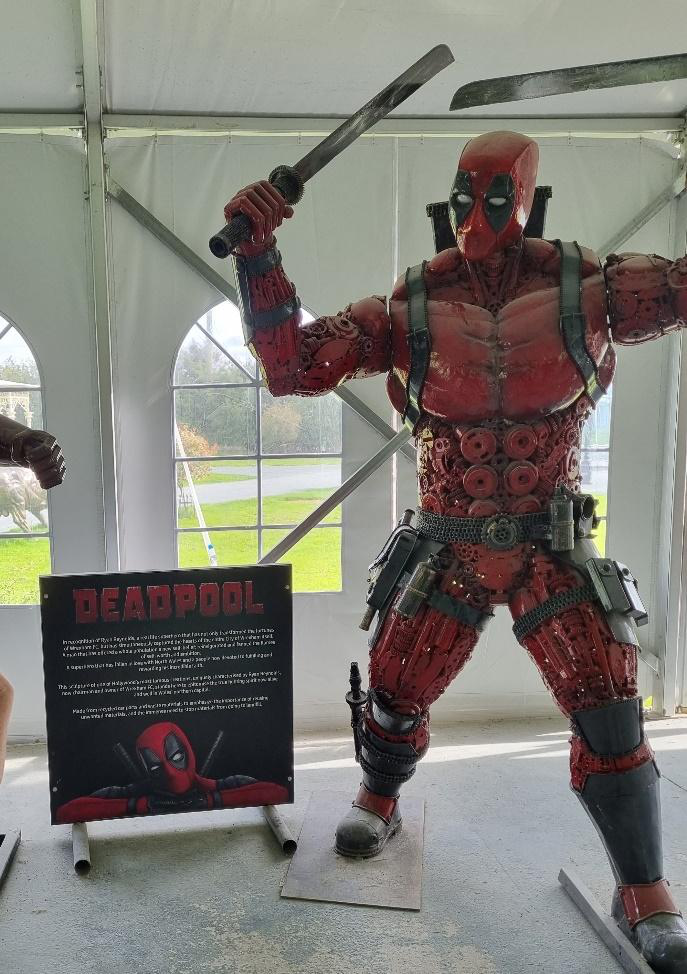

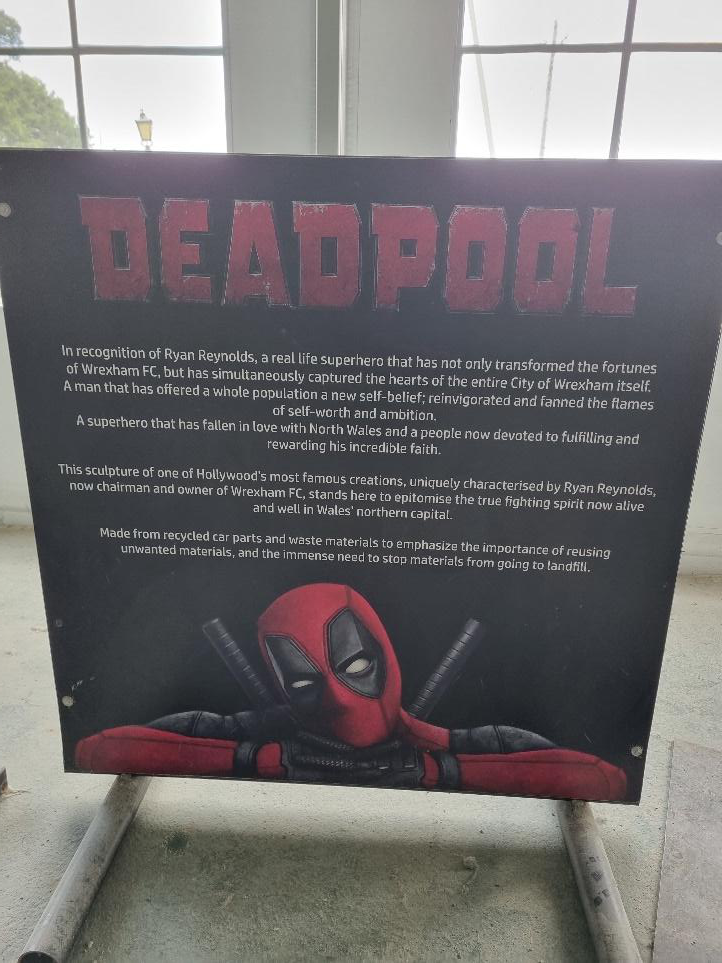

In September 2024, I visited the British Ironworks Centre in Oswestry, a small town in Shropshire, England that sits very near to the Welsh border. The center features a spectacular array of sculptures, including imitations of endangered animals and Hollywood intellectual properties such as Buzz Lightyear, Bumblebee and Darth Vader, all crafted from metal waste. As I was halfway through watching Welcome to Wrexham’s (FX, 2022-present) second season, I was particularly interested in the sculpture of Deadpool, which sat next to a sign paying tribute to Ryan Reynolds, the Hollywood star who is famous for playing the character in the Disney feature films and who, in 2020, joined Rob McElhenney, creator and star of It’s Always Sunny in Philadelphia (FX/FXX, 2005-present), to purchase Wrexham FC, a football (soccer) club in the nearby city of Wrexham. Having overseen the club’s rise from non-league football to League One (the fifth to third tier) and drawing global attention to it through the FX/Hulu/Disney+ documentary, the sign called Reynolds ‘a real life superhero that has … transformed the fortunes of Wrexham FC … captured the hearts of the entire city … [and] offered [North Wales] a new self-belief.’

According to the critical discourse, McElhenney and Reynolds’ decision to acquire Wrexham FC started after McElhenney watched another sports documentary, Sunderland ‘Til I Die. According to McElhenney, that documentary’s portrayal of the love that people in the city feel towards Sunderland FC, and how much their identity is entwined with their club, resonated with him as a passionate and dedicated Philadelphia native sports fan, as did its portrayal of a traditionally working-class place that had fallen on hard times following Thatcherism. After watching Sunderland ‘Til I Die during the pandemic, McElhenney says that he was inspired to give something back to a similarly working-class community. He approached Reynolds to join him on the venture, despite the two having never met in person, because he thought that they ‘would vibe’ and because he’s ‘incredibly entrepreneurial’ and ‘incredibly ethical’.[1]

This dynamic, with McElhenney and Reynolds purportedly wanting to give something back to a working-class community, is very much depicted in the first episode of Welcome to Wrexham. It focuses on McElhenney and Reynolds’ efforts to secure the backing of the Wrexham Supporters’ Trust, which took ownership of the club in 2011 and saved it from insolvency. The episode opens on a long-shot of the Wrexham High Street, which looks fairly worn down, followed by a montage of fans gathering to excitedly take pictures of the two stars after they arrive in the town center. The pair then arrive at Wrexham’s stadium, the Cae Ras or Racecourse in English. A caption informs us that it is the oldest active international football stadium in the world and close-ups of the stands depict it as needing renovation. McElhenney wonders how many people have watched the games there over the last 150 years, and he and Reynolds discuss the possibility that they might lose their investment and become the villains of the club, thereby highlighting what appears to be at stake.

The documentary also portrays McElhenney’s working-class background and heritage, as it sees him, his son and his father visiting the small house in Philadelphia where McElhenney grew up, with McElhenney describing Philly as a blue-collar town. As the documentary ends with McElhenney and Reynolds securing a massive majority of votes from the Wrexham Supporters’ Trust to approve their takeover, it legitimizes their agenda and relationship to the community to position them as custodians of the club and potential saviors of the town. This is essential to the success of Welcome to Wrexham as it reverse engineers the feel-good factor of many sports documentaries and does so, in part, by positioning McElhenney and Reynolds against many football club owners, who traditional fans often believe, at best, prioritize commercial goals that neglect or disadvantage them and, at worst, engage in shady dealings that risk jeopardizing the entire club.

While stardom might provide the most obvious frame for thinking about Welcome to Wrexham, the sculpture park got me mulling over a research project that I’d had in mind for some time: to explore the representation and construction of management in football. Broadly defined, management in football exists in several overlapping forms. It includes: 1) The management of football by governing bodies such as FIFA and the English Football Association, 2) The management of leagues such as the English Premier League and Germany’s Bundesliga, or England’s Women’s Super League and USA’s National Women’s Soccer League, 3) The management of football clubs, 4) Coaches whose main responsibility is managing team, 5) The management of players (including their reputations off the pitch), and 6) Fan management (including the management of fan engagement and participation in footballing rituals).

While management comprises a range of activities that usually take place at the mid-level between the macro and micro industrial levels,[2] it also represents a discursive construction and branded identity that sometimes intersects with, and is disseminated through, the media, often with the help of marketing and PR executives.[3] In these terms, management in football as a branded discourse can be understood as a product of convergences between the media and sports industries, or what David Rowe calls the ‘media sports cultural complex’.[4] More broadly, Branden Buehler has explored how a proliferation of representations, discourses and modes of sports management in media both reflects and drives significant transformations in culture and society, which includes the rise neoliberal ideology and financial capitalism, and a decline of manufacturing industries, that have contributed to an increased stature for the managerial classes.[5]

For example, Gianni Infantino, the White and straight Swiss Italian president of FIFA, has positioned himself as an anti-establishment figure to justify the organization’s often contentious decision-making. Ahead of Qatar’s hosting of the 2022 FIFA World Cup, Infantino gave a press conference in which he described himself as ‘feeling’ like a migrant and gay to deflect criticism of the state’s human rights abuses. This gestures to how a football management discourse can contribute to maintaining the media sports complex’s class, race, sexuality and gender based economic and cultural distinctions.[6] In fact, it reflects Buehler’s finding that the many White men spotlighted by managerial sports media often come to symbolize an imagined White masculine precarity while simultaneously ‘showing how these anxieties fuel fantasies of white masculine omnipotence’.[7]

Coaches who are responsible for managing the team and player performances also sometimes cultivate branded reputations that they can monetize to secure employment opportunities both within the game and outside it. After winning ITV’s 2018 series of I’m a Celebrity, a popular reality television contest that forces celebrities to survive in a jungle, Harry Redknapp, a former coach of West Ham United, was hired by BetVictor to promote the betting firm. Redknapp, whose savvy in the transfer market had led to him being compared to a fellow cockney and fictional wheeler dealer, Del Boy from the sitcom Only Fools and Horses (BBC One, 1981-2003), appeared in several commercials for the firm that saw him playing the role of a ‘smart speaker’ offering punters ‘tips and advice in his own, inimitable style’.[8] The commercial is satirical, in that it only appears to dispense with the data and metrics that are increasingly associated with sports management. In this sense, the commercial arguably promotes neoliberal principles by encouraging ‘the everyman’ to embrace financial speculation and, to do so, dispense with intuition to adopt a ‘calculative rationality’ mindset.[9]

Premier League clubs have also gained a reputation for seducing wealthy international investors, who tread a fine line between pursuing commercial expansion while retaining the loyalty of traditional fans. Following Chelsea FC’s acquisition by a consortium that included American Businessman Todd Boehly and private equity firm Clearlake Capital, the club courted controversy by appearing to prioritize international audiences over local fans. For instance, the club scrapped subsidies for fans’ coach travel to away games while Boehly encouraged the Premier League to pursue expansion through the sale of television rights to a ‘global platform’, specifically Netflix.[10] Boehly’s Chelsea tenure has become just one example, in many fans’ eyes, of the shady or incompetent conception of club ownership, against which McElhenney and Reynolds position themselves as ethical custodians of Wrexham FC.

Yet the impressions of authenticity surrounding McElhenney and Reynolds’ takeover that are bolstered through the documentary form, and which function to create the sense that the two of them are self-serving, require scrutiny. The documentary’s repeated claims that they are significantly financially exposed from their investment is sometimes played for laughs and needs to be taken with a pinch of salt. The takeover opened several lucrative commercial opportunities that involved getting the show, which is now entering its fourth season, commissioned, while their star power has also allowed McElhenney and Reynolds to secure major club sponsors such as TikTok, a platform that they regularly use for the dissemination of Wrexham FC-related videos. Welcome to Wrexham’s production credits also include 3 Arts Entertainment, which is a production and talent management company to which McElhenney is signed, alongside McElhenney’s More Better Productions, the production arm of his More Better Industries. These credits point to the significant number of companies and personnel that are involved in the Welcome to Wrexham project that are hidden behind McElhenney and Reynolds’ branded identities.

Watch on TikTok

The documentary is also meant to appeal to national and international (especially American) pay-television and streaming subscribers. The show juxtaposes its Hollywood celebrity owners with ideas and images of Wrexham’s neglect following the decline of its traditional industries. The strategy has clearly been successful. On a more recent trip I took to Wrexham, I visited The Turf pub that features in the series and sits next to The Racecourse and found Wrexham locals mingling with families from the United States, Canada and Australia. While the vibe was jovial, the documentary perspective is arguably problematic as it risks making a spectacle of a working-class community and making wealthy benefactors saviors for a group of people who might otherwise appear unable to thrive on their own.

This risks making the future success of the town and its people appear to be dependent on McElhenney and Reynold’s continuing involvement and hopeless in the event of their withdrawal. Such fears were expressed by one local business owner that I spoke to, who told me that they had seen a decrease in footfall in one of the city center’s main streets, which they attributed to a waning of the hype around the takeover. Such perspectives are at odds with the portrayal of McElhenney and Reynolds as heroes that appear in ‘official’ media such as Welcome to Wrexham and the sculpture park sign. So, although McElhenney and Reynolds display affection for the working-class, their managerial posturing arguably ends up advocating for abandoning the manufacturing industries in favor of service sectors based around the production of non-material goods by immaterial labor. As a result, it points to the potential value of examining interactions between the different iterations of the football managerial branded discourse that are disseminated in the official media and local constituencies including fans and community members.

Image Credits:

- A Deadpool sculpture at the British Ironworks Centre in Oswestry (author’s personal collection)

- A tribute to Deadpool star and Wrexham FC co-owner, Ryan Reynolds (author’s personal collection)

- An image of Wrexham from the season 1 trailer (author’s screen grab)

- Harry Redknapp as a smart speaker in a BetVictor commercial (author’s screen grab)

- Reynolds and McElhenney on TikTok selling club shirts

- The Turf, a local pub and tourist attraction (author’s personal collection)

- Anon, ‘“Always Sunny” Creator Rob McElhenney on his Pandemic Purchase: a Welsh Soccer Team Fresh Air’, NPR, 12 June 2024. [

]

- Derek Johnson, Derek Kompere and Avi Santo, ‘Introduction: Discourses, Dispositions, Tactics: Reconceiving Management in Critical Media Industry Studies’, in Johnson, Kompere and Santo (eds.) Making Media Work, New York: New York University Press, 2014, p. 11. [

]

- Ibid, p. 2-3. [

]

- David Rowe, Global Media Sport: Flows, Forms and Futures, London: Bloomsbury, 2011, p. 4. [

]

- Branden Buehler, Front Office Fantasies: The Rise of Managerial Sports Media, Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 2023, pp. 21-4. [

]

- Rowe, p. 9. [

]

- Buehler, p. 26. [

]

- Anon, ‘Make Your Best Bet: BetVictor’, Mr. President, N.D., https://mrpresident.co/casestudy/hey-harry-make-your-best-bet/ [

]

- Buehler, p. 24 [

]

- Paul MacInnes, ‘Boehly believes Netflix could ‘maintain’ Premier League’s global success’, The Guardian, 27 February 2025, https://www.theguardian.com/football/2025/feb/27/todd-boehly-chelsea-netflix-maintain-premier-leagues-global-success-crystal-palace [

]