“Scan to Join!”: Selfie Fan Cams and the Sporting Event

Laurel P. Rogers / University of Texas at Austin

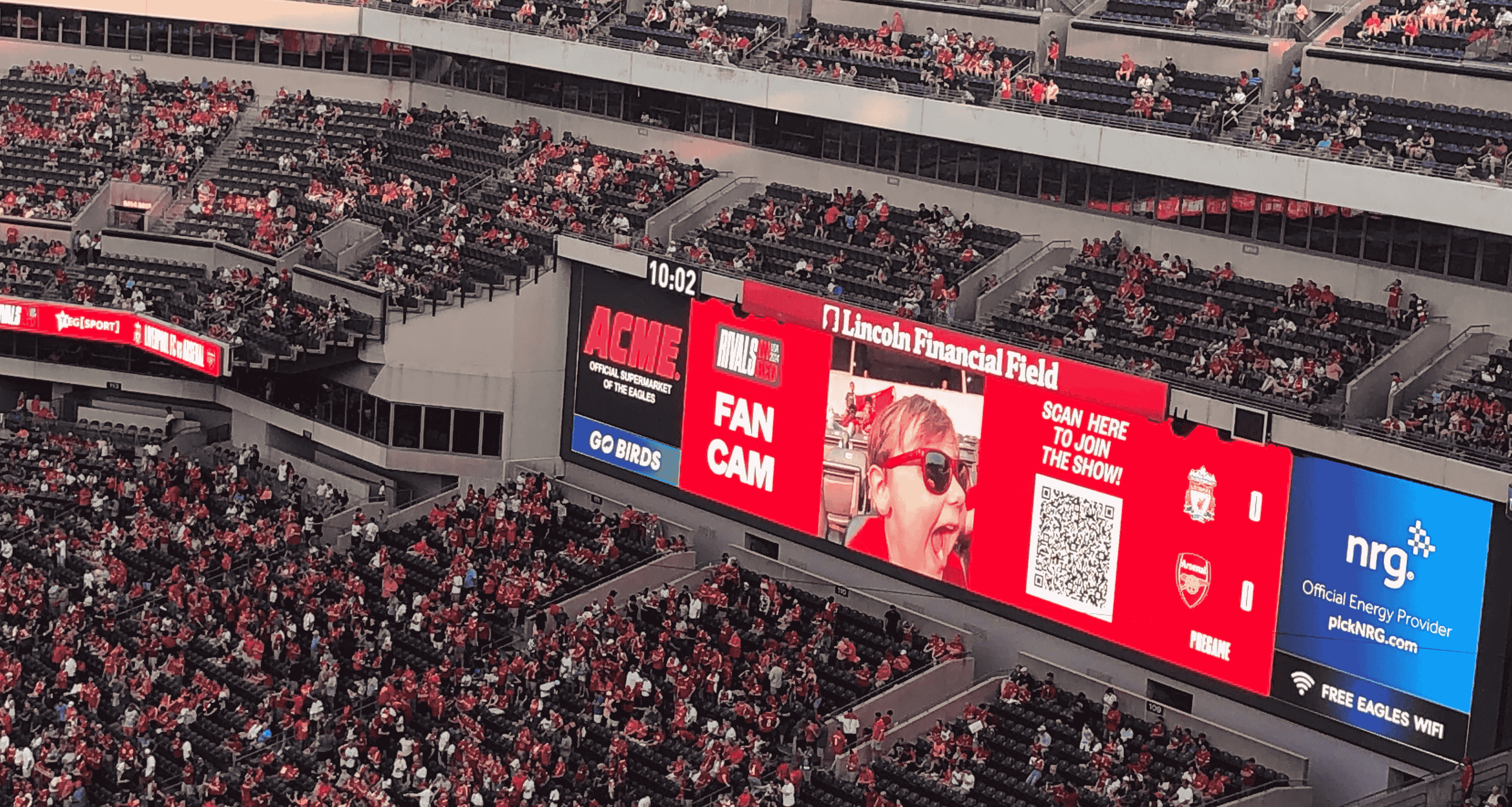

Despite growing up in hockey-obsessed Canada, I would not call myself a sports fan. With the biannual exception of the Olympics, I don’t follow any particular sport leagues or teams, and any engagement of mine is purely second-hand as reported through my more sports-engaged friends. However, I am not immune to the energy of a live sports event, and so this July I found myself in the upper stands of Philadelphia’s Lincoln Field stadium, ready to watch a pre-season friendly match between the English Premier League’s Liverpool and Arsenal football clubs. As the pre-game activities ramped up, Lincoln Field’s giant digital scoreboards advertised a way to engage with the “fan cam” by scanning a QR code to “join the show” (Figure 1).

At first, I was confused — I am more familiar with the term “fancam” referring to a style of video popularized by K-pop fandom, where a camera follows one single performer through an entire performance or appearance, to the exclusion of other members and/or the full group.[1] (This style of fan cam is starting to enter the sports arena, though, likely thanks in part to Tottenham Hotspur’s Korean soccer superstar Son Heung-min (Figure 2).) However, in sports terms, “fan cam” covers any moment that the camera is turned upon the stands, highlighting the bodily presence of the spectators and rewarding those who visibly and enthusiastically perform their fandom, by wearing jerseys, painting their faces, displaying signs, celebrating, dancing, etc. Even the sports-uninformed like myself are probably familiar with the type of fan cam known as the “Kiss Cam,” where pairs assumed to be couples are singled out and displayed on the stadium’s screens while the crowd encourages them to kiss (Figure 3).

As such, fan cams function as one of many stadium “atmosphere-building” activities, rousing the crowd’s energy and enhancing the experience for in-person spectators. At times, the fan cam can even become a site of spontaneous, playful co-creation between spectators and live event producers (Figure 4). In observing Lincoln Field’s fan cam, I noticed that children and families were an especially popular subject of the fan cams chosen to be displayed, highlighting and encouraging the generational transmission of sports fandom (as well as being often pretty cute). (Perhaps not incidentally, Reifurth, Bernthal, and Heere note that in-stadium activities like fan cams and the appearance of mascots provide children who may not have the attention span to focus on the game with opportunities to expend physical energy and the potential to gain attention and praise from the adults around them — and potentially the entire stadium — who are otherwise distracted by the game.[2]) Alternately, the fan cam can also become a site of contestation, such as when lesbian WNBA fans protested their lack of fan cam representation in 2002.

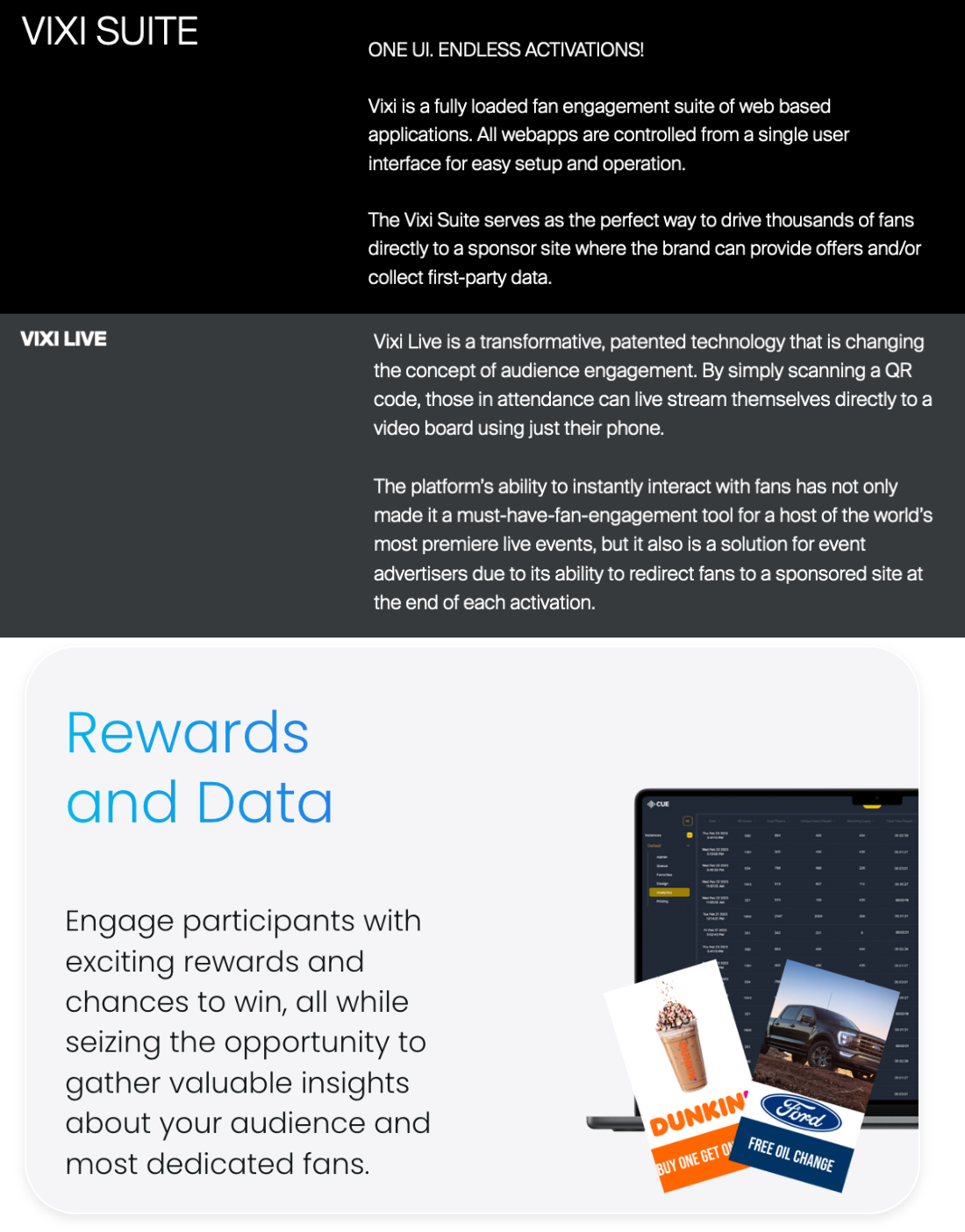

Unlike traditional fan cams, the fan cam promoted on the screen at Lincoln Field was not operated by professional in-stadium camera operators; instead, the screen invited spectators to turn their cell phone cameras on themselves. In the past few years, sports franchises and venues have increasingly incorporated spectator’s devices, which the COVID-19 pandemic has only accelerated. After pandemic experiments such as projecting fans into screens in the stadium via Microsoft Teams, Vixi Live’s Matt Marcus said that experiencing the “power of people having control of their own video and seeing themselves on the broadcast or in the venue” prompted the company to develop its selfie fan cam technology. The Vixi Suite, now used by the NBA, MLB, NFL, and numerous other sports and events clients, not only allows fans to turn the fan cam on themselves, but also incorporates 3D graphics and “AI” filters and transformations (Figure 5). Cue, another cell phone “fan engagement” company, also offers technology to run games and trivia with prize distribution as well as a synchronized light show. As one director of game operations and events notes, these ventures offer sports franchises a further way to incorporate cellphones into the in-stadium experience, rather than treating them as a “distraction” from the sporting event. This is all part of a trend towards turning the arena into a “media platform,” as Steven Secular outlines in his recent monograph The Digital NBA: How the World’s Savviest League Brings the Court to Our Couch. Not only are camera placements and internet technology requirements now shaping the design of arenas, but team apps allow fans not only to view news, statistics, and other “exclusive content,” but also order food to their seats and monitor concession and washroom queue wait times when in the arena.[3]

These selfie fan cams are often pitched to spectators as a way of “democratizing” the fan cam. Selfie cams are “more up-close-and-personal,” providing a more intimate, direct experience than a zoomed-in arena camera — both to those being filmed and those watching in the stadium. You no longer need to be seated in just the right area for a fixed camera to catch; instead, even fans in the far nosebleed sections can choose to turn their cameras on themselves. Further, the opt-in mechanism means that the kiss cam will no longer accidentally focus on siblings, and fans who do not want to be exposed to the fan cam can be secure in the knowledge that they will not appear on the big screen.

Fan cams are often considered only within the context of the arena. Fan cams provide in-stadium crowds with a diversion during play stoppage, offers fans the opportunity to be recognized in the performance of their fandom, and build energy within the stadium. This not only enhances the experience in the stands, but also, as Secular notes, is key in the creation of an engaging mediatized (i.e. televised or streamed) version of the game — which is key as sports franchises and leagues increasingly make their money not through ticket sales but through the licensing of their media rights.[4] In theory, these selfie fan cam technologies offer the opportunity to include fans outside the stadium as well, as Cue’s FanSee suggests by offering to “showcase any fan, anywhere … whether it’s across the stadium or across the nation.” As Boria Majumdar and Souvik Naha note in an article speculating on COVID-19’s effect on sports broadcasting, this has the potential to extend participation in the live game to those fans who are excluded from the arena because they are unable to afford travel and/or tickets.[5] However, my experience at Lincoln Field and my research for this piece suggests that, at least for sports, this has not come to fruition, and the technology is being used in-stadium only, perpetuating the exclusivity of the in-stadium experience.

While press coverage and marketing might tout the benefits to fans, the true value of all these fan “engagement” ventures is, of course, in the access to data. Secular describes how the Sacramento Kings’ app is used to monitor user data, including “min[ing] fans’ social media presence.”[6] The Famous Group’s Vixi Suite is unabashed in highlighting this aspect of their products: “The Vixi Suite serves as the perfect way to drive thousands of fans directly to a sponsor site where the brand can provide offers and/or collect first-party data,” the website says. Vixi Live specifically is not just a “must-have-fan-engagement tool for a host of the world’s most premiere live events, but it also is a solution for event advertisers due to its ability to redirect fans to a sponsored site at the end of each activation” (Figure 7). In this way, these apps are akin to “activations” like those at San Diego Comic-Con, which offer exclusive “immersive experiences” in return for free word-of-mouth advertising on social media as well as, crucially, access to participants’ user data.[7]

Beyond the ethical concerns inherent in these data mining ventures masquerading as “fan engagement” apps, my experience of the selfie fan cam didn’t necessarily provide any of the immersive, intimate, or personal experiences that they purport to offer. The quality of the cell phone streams were often low, blurry and pixelated, and fans’ excitement at being featured on the screen often caused them to move or shake the camera as they jumped and waved excitedly, which unfortunately only exacerbated the blur and lag. Personally, I’d prefer a high-quality image of a cute kid in a jersey as transmitted by an in-arena camera — but then, as a self-proclaimed “sports neutral” person, I’m probably a less valuable data point anyway.

Image Credits:

- Lincoln Field’s invitation to “join the show.” Photo by Katie Hartzell, used with permission.

- A Son Heung-Min fancam

- A kiss cam goes humorously wrong at a hockey game

- The fan cam as co-creation

- Vixi Capture offers fans the ability to “transform” their uploaded images

- Cue’s FanSee, a selfie fan cam technology

- Marketing copy from Vixi Suite and Cue’s FanSee (author’s screenshots)

- Muxin Zhang, “Fandom Image-Making and the Fan Gaze in Transnational K-Pop Fan Cam Culture,” Transformative Works and Cultures 42 (March 14, 2024): para. 1.1, https://doi.org/10.3983/twc.2024.2463. [↩]

- Katherine Rose Nakamoto Reifurth, Matthew J. Bernthal, and Bob Heere, “Children’s Game-Day Experiences and Effects of Community Groups,” Sport, Business and Management: An International Journal 8, no. 3 (June 14, 2018): 264–65, https://doi.org/10.1108/SBM-11-2017-0077. [↩]

- Steven Secular, The Digital NBA: How the World’s Savviest League Brings the Court to Our Couch (Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press, 2023), 79–80. [↩]

- Secular, 51–52; Secular, 15. [↩]

- Boria Majumdar and Souvik Naha, “Live Sport during the COVID-19 Crisis: Fans as Creative Broadcasters,” Sport in Society 23, no. 7 (July 2, 2020): 1091–99, https://doi.org/10.1080/17430437.2020.1776972. [↩]

- Secular, 94–95. [↩]

- See, for example, Melanie E.S. Kohnen, “The Experience Economy of TV Promotion at San Diego Comic-Con,” International Journal of Cultural Studies 24, no. 1 (January 2021): 157–76, https://doi.org/10.1177/1367877920935888. [↩]

Really I appreciate the effort you made to share the knowledge. The topic here I found was really effective to the topic which I was researching for a long time.

Go 36’s

Hey people!!!

HAVE A NICE DAY