Amazon MGM Studios not playing by its book in India

Mansa Narain / University of Texas at Austin

“In terms of a struggle over hegemony, the inclusion of minorities through diversity schemes, even though they serve to reinforce whiteness, can still be read as a form of progress of sorts. While Hall admits that the gains made by marginality in popular culture amount to nothing more than segregated visibility, his point in fact is that, in a war of position, segregated visibility represents a gain nonetheless. Although I argue that the reason minority access to the cultural industries is impeded is not in spite of diversity initiatives, but because of them, I would also go as far as saying that, when successful cultural transruptions do occur, it is because of these policies, however much it may feel as if they happened in spite of them.”

Anamik Saha (2018, 83)

This is an excerpt from Saha’s book, Race and the Cultural Industries, in which he engages with various scholars (Ahmed 2012; Gray 2013; Leong 2012; Hall 1981/2020; Hall 1992/2020) who critique diversity initiatives for being a form of governance, managing the inclusion of minorities in ways that maintain the existing power dynamics. Here, Saha highlights Hall’s acknowledgement that even though diversity initiatives may reinforce whiteness, they can still be a step towards greater cultural justice by increasing the visibility and presence of minorities. But what happens when these diversity initiatives exist but are not implemented successfully? And what happens when they are publicized as a “mandate” (Maitri, 2024) but are not so on paper?

In June 2021, Amazon MGM Studios launched its Inclusion Policy and Playbook.[1] The playbook states, “at Amazon Studios, we know that our set environment can influence the outcome of the content we produce. We aim to foster a culture that is open, inclusive, and respectful of our creatives, cast, and crew in a way that respects their background, gender, race/ethnicity, sexual orientation, age, disability, size, national origin, religion, or any other aspect of identity. We honor differences, and have zero tolerance for harassment or discrimination of any kind” (Amazon MGM Studios, 2021). In the playbook’s press release, Amazon states that through the Playbook it “extends its commitment to diversity, inclusion, and equity for its content and productions, as well as a Playbook with guidelines for its collaborators in the creative community” (Amazon Studios, 2021). However, just in the next statement, they describe these policies as guides that offer detailed and actionable “recommendations” (Amazon MGM Studios, 2021). Use of the term recommendations implies their weak sincerity in their commitment towards their diversity initiatives. This is reflective in their presence in India, especially in their relations with their collaborators whose work they license to showcase on their platforms. In India, they are focusing their diversity campaigns on inclusion only to a singular category of underrepresented individuals – females.[2] This, in itself, is a statement on their lack of commitment towards their diversity initiatives when operating in India. Furthermore, instead of incentivizing their collaborators to be more inclusive by closely adhering to their playbook, they are profiting from the tokenistic approach of their collaborative media producing agencies.

To answer my previous question — what happens when these initiatives are not implemented successfully? — organizations will commodify these initiatives to their benefit while caring less about if they will be held accountable for their words. This is evident from Amazon’s business practices in India. Though they have put little effort into having gender parity on their production sets, they highlight it to commodify feminism to their advantage. To echo their diversity initiatives in India, that are hyper focused on creating more inclusive spaces for women in the creative industries, Amazon Prime Video India, in December 2022, launched a YouTube channel, called Maitri: The Female First Collective. The channel showcases long-form group discussion videos among female members of the cast and crew of Amazon Originals along with other occasional participants who are female executives of other media agencies. These discussions are about the struggles female workers go through at work across departments and positions within the regional entertainment industries in India. They discuss issues that majority of female workers in said industries face, such as sex-based discrimination during hiring for work across creative departments, especially for outdoor on-location shoots, misogynistic and sexist behavior at the place of work, ageism, unequal pay, inadequate sanitation facilities for females, lack of privacy to change costumes for actors, lack of safety for females on sets, sexual harassment, etc.

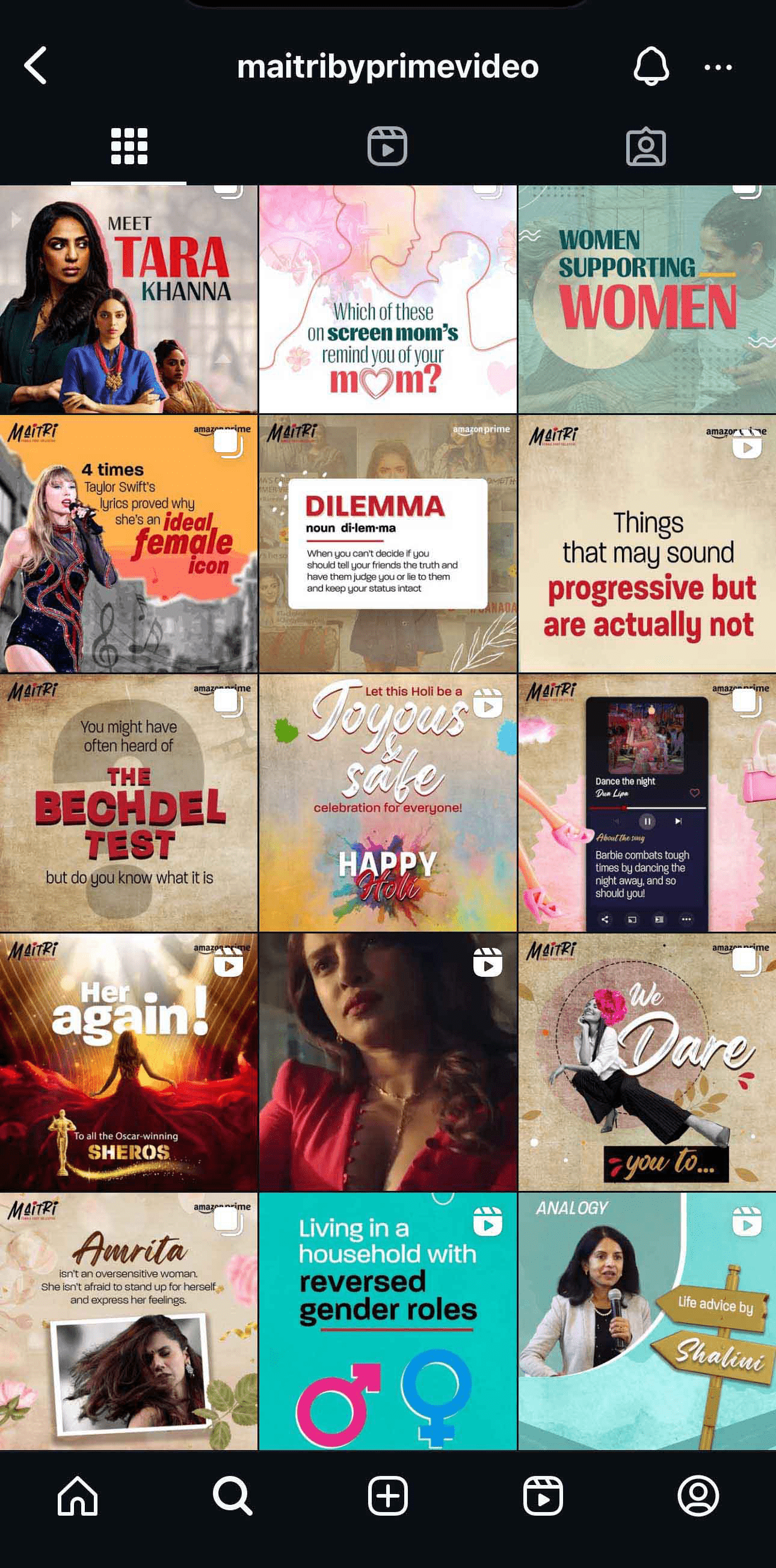

Along with this YouTube channel, Amazon Prime Video India is also promoting this initiative on other social media platforms like Facebook and Instagram. Aparna Purohit, the then Head of India and South East Asia Originals at Amazon Prime Video, is also shown participating in these conversations. It is to be noted that contrary to language used in the press release from Amazon about their Inclusion Playbook, Purohit in one of the Maitri episodes has mentioned that Amazon Prime Video India have made it a “mandate” (Maitri, 2024) to have at least one woman in the writer’s room. However, this proclaimed “mandate” has not been extended to Amazon’s collaborators. This approach is exemplar to tokenism and is advised against in their playbook.

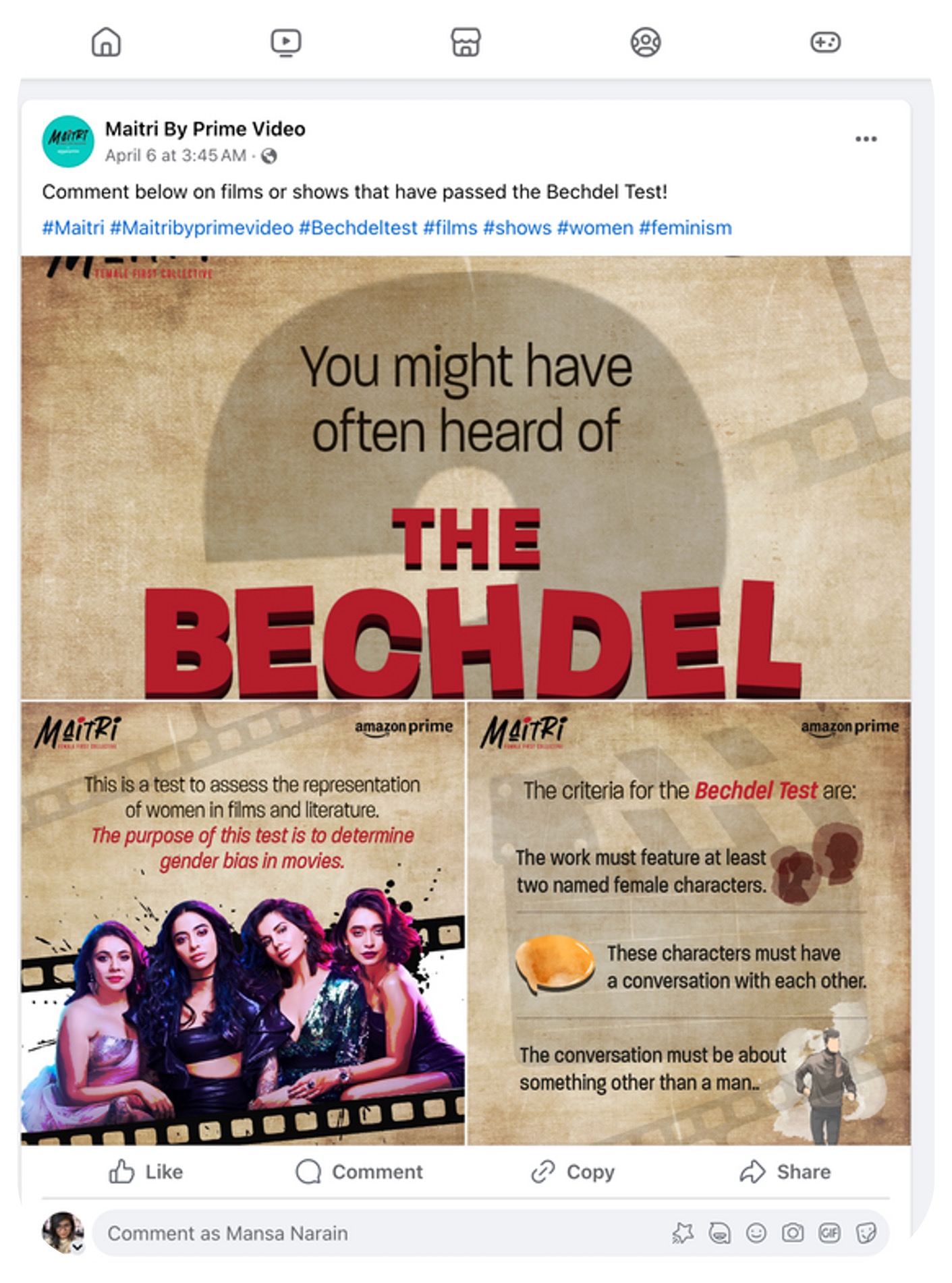

Sarah Banet-Weiser writes, “… the focus on inclusion by popular feminism makes it specifically corporate-friendly; it has benefited from decades of neoliberal commodity activism, where companies have taken up women’s issues, especially those that have to do with individual consumption habits, as a key selling point for products (Mukherjee and Banet-Weiser, 2012)” (Banet-Weiser et al., 2020). Maitri episodes, being a top-down-initiative, are an example of such neoliberal commodity activism. They are seemingly informal discussion between female workers from the entertainment industries in India who are in association with Amazon Prime Video; and in these discussions, there are moments when the conversation among these female workers, having their own distinct understanding of feminism, echo the popular and postfeminist sensibilities of feminism that have been subjected to scholarly criticism. Banet-Weiser writes, “popular feminism circulates in an economy of visibility … in a media context in which if you are visible, you matter” (Banet-Weiser et al., 2020). Through posters and infographics, Maitri is promoting the use of the Bechdel Test as a parameter to analyze women on its social media accounts as well, particularly on Facebook and Instagram, thereby increasing visibility (see figures below). On these social media platforms, they are also engaging with ideas of women’s safety, identity exploration, while also promoting their Prime Video content.

Purohit, on Maitri and in other interviews, has also mentioned the ‘O Womaniya!’ report, an annual survey report by Ormax Media (a consulting firm for the Indian media & entertainment industry) and Film Companion (an English language entertainment journalism platform) in collaboration with Amazon Prime Video. The report does use statistics on the sex ratio on media production sets along with the Bechdel Test as a parameter of analysis for sex representation, in addition to the comparison of the duration of on-screen dialogue delivery by a male versus female character in a trailer that is used to market the film. The commodification of quantitative research is to boost their “economy of visibility” which then will reflect as a rise in their Prime membership. Ishita Tiwary explains how Amazon Prime Video is different from other streaming platforms because of its “embedding of its video platform within the larger umbrella of services that it offers” (Tiwary, 2020) as a part of its wider e-commerce operations. This way Amazon integrates its customers within a portfolio of digital goods and services. They use their Prime memberships as a significant source of revenue for themselves. Hence, there is ample motivation for them to make their prime membership attractive by offering exclusive services[3] to their customer base. Amazon is benefiting from such visible activism but is not doing the work to bring change when it comes to having diverse representation on its sets.

Amazon MGM Studios, when collaborating with local media agencies, gives extremely high monetary incentives which then dictate their professional relationship. These local media agencies are then highly incentivised to trade away their autonomy and agency. Saha, drawing on cultural industries theorists like Hesmondhalgh, argues that even alternative media are influenced by the rationalization and bureaucratization processes of dominant media oligopolies (Saha, 2018). This means that the power of large media corporations influences the rest of the industry not just in ideology but also in establishing norms. This systemic influence challenges the autonomy of smaller, alternative media outlets, even those meant to serve marginalized communities. This theory is reflected in a series of interviews that I conducted with representatives from such alternative media outlets.

In speaking to female workers at local companies who contract with Amazon, workers expressed a profound sense of frustration and disappointment. They felt that their concerns, particularly regarding issues like sexual harassment, were inadequately addressed because the bureaucracy within these collaborative agencies meant there was no way for these workers to access Amazon. Further, employees experienced pressure within their own companies against filing formal complaints for fear Amazon would not collaborate with those media agencies in the future. There was also personal fear for freelancers of being boycotted by the industry. Other interviewees shared that in working with partner media agencies, Amazon provided no guidelines on inclusivity in terms of crew. They only advised on the matters of casting for primary characters, and only required revisions based on concerns about inappropriate portrayal of women in select sections of the script.

All these instances are evidence of Amazon not incentivizing their collaborators to be more inclusive by closely adhering to their playbook and in turn reflect Amazon’s failure in even “recommending” (Amazon Studios, 2021) as per their inclusion playbook. Moreover, Purohit, in one of the Maitri episodes, talks about them offering a database of female creative workers in the industry, but that does not seem to be happening for all its projects. Circling back to Saha’s argument from the beginning, I agree with him in the thought that diversity initiatives that bring policy changes serve their purpose but only when they are implemented successfully; the purpose of it being progress for underrepresented communities. Therefore, I call for more scholarship that studies the pitfalls that occur in the execution of these diversity initiatives in the media industries, particularly on why they occur and how the pitfalls can be avoided.

Image Credits:

- Screenshot of Amazon MGM Studio’s CCDEIA website (author’s screen grab)

- Purohit using the term “mandate” | Maitri: Female First Collective | The First International Edition, Video on YouTube by Maitri by Prime Video

- Figure 2: Screenshot of Maitri by Prime Video’s Facebook post on the Bechdel Test (author’s screen grab)

- Figure 3: Screenshot of Maitri by Prime Video’s Instagram profile (author’s screen grab)

References:

Ahmed, Sara. On Being Included: Racism and Diversity in Institutional Life. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2012.

Amazon MGM Studios. Amazon MGM Studio Inclusion Policy and Playbook. Culver City, CA: Amazon, 2021. https://www.ccdeia.com/playbook

Amazon MGM Studios. “Amazon Studios Releases Inclusion Policy and Playbook to Strengthen Ongoing Commitment to Diverse and Equitable Representation.”Culver City, CA: Amazon, 2021. https://press.aboutamazon.com/2021/6/amazon-studios-releases-inclusion-policy-and-playbook-to-strengthen-ongoing-commitment-to-diverse-and-equitable-representation

Banet-Weiser, Sarah, Rosalind Gill, and Catherine Rottenberg. “Postfeminism, popular feminism and neoliberal feminism? Sarah Banet-Weiser, Rosalind Gill and Catherine Rottenberg in conversation.” Feminist Theory, 21(1), 3-24. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1177/1464700119842555

Banet-Weiser, Sarah. Empowered: Popular Feminism and Popular Misogyny. Durham: Duke University Press, 2018.

Gray, Herman. “Subject(Ed) to Recognition.” American Quarterly 65.4 (2013): 771–798.

Fraser, Nancy. Justice Interruptus : Critical Reflections on the “Postsocialist” Condition. New York: Routlege, 1997.

Hall, Stuart. “Notes on Deconstructing ‘the Popular’ [1981].” In Essential Essays, Volume 1, 347–361. New York, USA: Duke University Press, 2020.

Hall, Stuart. “What Is This ‘Black’ in Black Popular Culture? [1992].” In Essential Essays, Volume 2, 83–94. New York, USA: Duke University Press, 2020.

Hesmondhalgh, David. The Cultural Industries. 3rd ed. London: SAGE, 2013.

Leong, Nancy. “Racial Capitalism.” Harvard Law Review 126.8 (2013): 2151–2226.

Maitri by Prime Video. “Maitri: Female First Collective | The First International Edition”, YouTube Video, 43:45, January 31, 2024. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vPVxs0QRqXo

Mukherjee, Roopali, and Sarah Banet-Weiser. Commodity Activism: Cultural Resistance in Neoliberal Times. New York: New York University Press, 2012.

Ormax Media, Film Companion, O Womaniya! 2021. Mumbai, Maharashtra: Ormax Media, 2021. https://owomaniya.org/

Ormax Media, Film Companion, and Amazon Prime Video. O Womaniya! 2023. Mumbai, Maharashtra: Ormax Media, 2023. https://owomaniya.org/

Saha, Anamik. Race and the Cultural Industries, Polity Press, 2018.

Tiwary, Ishita. “Amazon Prime Video: A Platform Ecosphere.” In Platform Capitalism in India/Edited by Adrian Athique, Vibodh Parthasarathi, 87–106. Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2020.

Footnotes:- The Inclusion Playbook has been formulated in collaboration with Dr. Stacy Smith and Dr. Katherine Pieper of USC’s Annenberg Inclusion Initiative, Brenda Robinson of the International Documentary Association, and Gamechanger Films, along with other leading organizations which are devoted to advancing the visibility and responsible depictions of underrepresented people. [↩]

- The use of the term female aligns Amazon’s statements and is consistent with their initiative in India that focuses on cis-gendered women only. [↩]

- Prime Video, for Amazon, is one of the many services by which they are making their Prime membership more desirable to their customers — free shipping, discounts and rewards at Whole Foods, access to services like Amazon Fresh, Prime Try Before You Buy, Prime Early Access, Amazon Elements, Prime Music, Prime Reading, Amazon First Reads, Amazon Photos, Amazon Channels, etc.). Even within Prime Video, they are taking measures to make their exclusive content by making it desirable by catering to the local tastes of their audiences. [↩]