Building the Television Network: AT&T’s Southwest Extension and the Fort Worth Rodeo

Selena Dickey / Furman University

“In addition to being quite the event, coaxially speaking,” wrote a reporter for Newark Star-Ledger in 1952, recapping the previous weekend’s television fare, “[the rodeo] was a good show in Western tradition, with cowboys and horseflesh aplenty…”[1]

Oddly enough, Newark, New Jersey hadn’t held a rodeo that weekend. It was, in fact, Fort Worth, Texas, nearly 1,600 miles away, that had. But for the first time, in January 1953, viewers in Newark—and from across the country—had watched it live.

For 21st-century readers, this phenomenon seems hardly noteworthy. Nearly all of the television we receive now originates from across the globe (especially as an ever increasing share of U.S. households access television solely through their broadband connection), and watching live-streams is par for the course.

But if we examine the infrastructural logistics of early television—particularly, as the article hints, at its coaxial developments—we’d find that this live “stream” of the rodeo and its horseflesh aplenty carries much more significance. This seemingly small blip in Texas media history actually reveals how the growth of nationwide, synchronous television service was a much more contingent, incremental, and local process than most media historians have previously acknowledged.

Let’s rewind another four years.

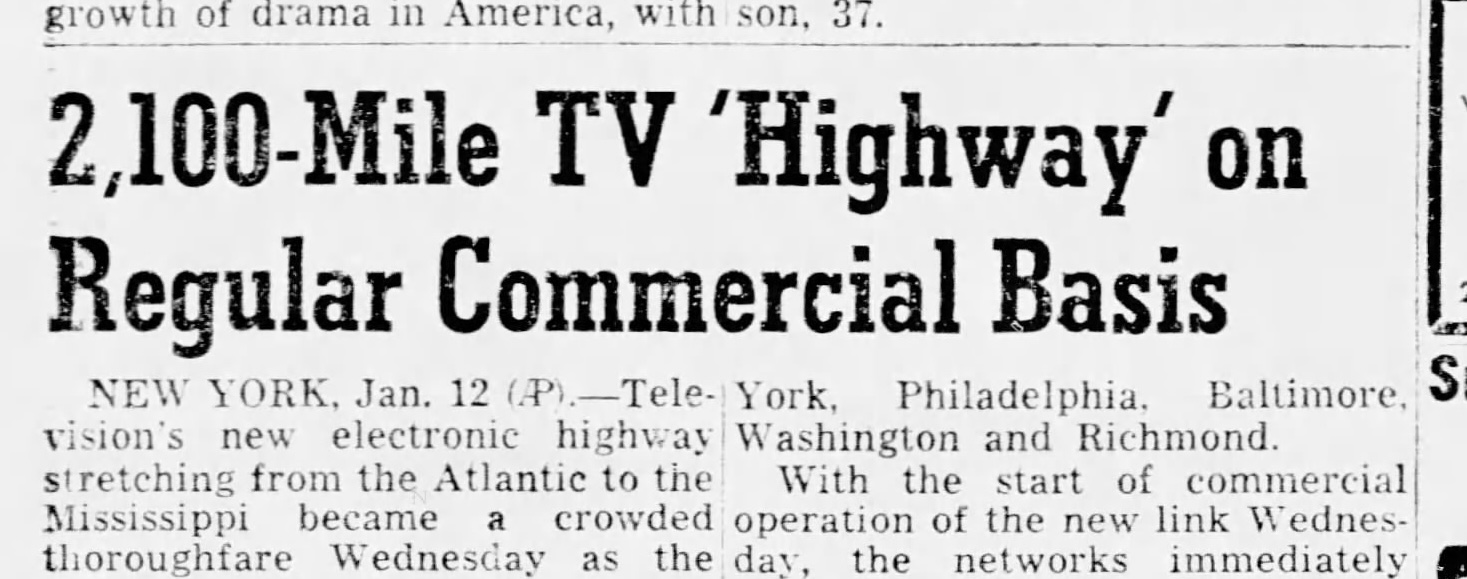

On January 12th, 1949, an item in the Fort Worth Star-Telegram announced the opening of AT&T’s 2,100 mile “TV highway” for regular use (see fig. 2). This new electronic route, made up of coaxial cable and microwave relays, had now “connected the separate East Coast and Midwest television hookups of the Bell system,” enabling live pickups of network programming from the New York City production center to “14 cities with 32 stations, more than half the total now in operation.”[2]

Notice that the article refers to two different networks: (1) the telecommunications network primarily owned by AT&T that carried interstate communications traffic comprised of telephone calls but also television signals. And (2) the commercial broadcasting networks made up of a few powerful players (NBC, CBS, ABC, etc.) and their local station affiliates. The quasi-symbiotic relationship between these two networks had, in fact, been in place since nearly the beginning of commercial broadcasting, when AT&T let go of its plans to dominate the airwaves and ceded its radio stations to RCA in exchange for exclusive signal distribution rights in 1926.

I point all of this out because when we examine early television’s infrastructural logistics, we inevitably must more closely attend to the history of telecommunications. Many popular television histories have acknowledged the telecom-TV relationship, such as the opening of AT&T’s transcontinental leg of the “TV highway” two years after the East Coast-Midwest linkup, a connection that’s typically cited as the beginning of simultaneous nationwide television service.[3]

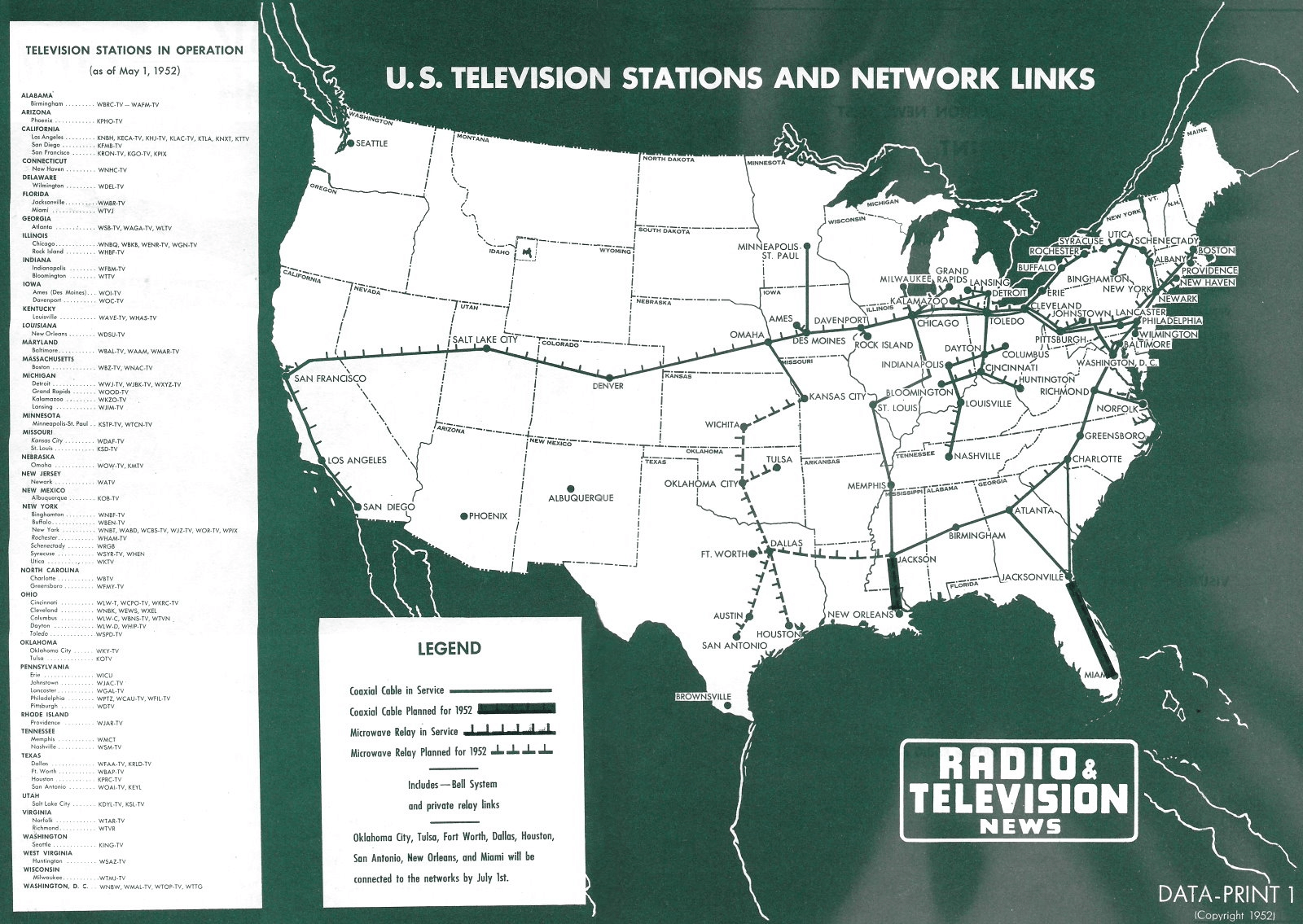

But a 1952 map (see fig. 1) shows that nationwide televisual simultaneity has been more than a little overstated. First, particularly in large swaths of the Mountain West and Southwest, there simply were no television stations, a problem stemming from the Federal Communication Commission’s 1948-1952 licensing freeze. And yet, even for those few, far-flung, “fringe” stations that had received a license before the freeze, the coast-to-coast networking infrastructure excluded nearly all of them. What becomes clear, instead, is how much of the country did not have an on-ramp to this TV highway.

One of these excluded—or “non-interconnected”[4]—stations was Fort Worth’s WBAP-TV (now KXAS-TV), which went on the air in 1948, not only making it the first TV station in Texas but also making Fort Worth one of only two pre-freeze “Television Cities” between Los Angeles and St. Louis. As broadcast historian Erik Barnouw describes them, pre-freeze TV stations were sites of laboratory-like experimentation and testing.[5] Station owners, managers, and producers had to chart new paths through the tricky terrain of filling out the schedule amid unknown revenue streams, skyrocketing costs, and finicky technology.

Figure 4: WBAP-TV’s See Saw Zoo, hosted by Dean Raymond, 1949

Richard Schroeder has also detailed how WBAP-TV, like many non-interconnected stations at the time, built its schedule on three main programming sources: live studio productions, which were largely ad-hoc and ad-libbed, filmed with just two bulky cameras and a limited staff (see figure 4); network content—or kinescopes—which were filmed by the network (in the case of WBAP-TV, with its dual affiliation, these would have come from NBC and ABC) and then “bicycled”[6] to the affiliate; and low-budget films, which the station licensed from syndicators and used to fill time and to ensure viewers’ sets would have a picture to pick up.

For the most part, these sources of programming gave local stations a degree of autonomy. WBAP-TV had the choice of airing kinescoped network content on days or at times that better met the demands of local sponsors and viewers. Interconnected stations, on the other hand, had to air network content when it was “live on the coax”; the only choice left for them was whether to pick it up or not.

As construction of the television distribution network continued, though, WBAP-TV and other non-interconnected stations faced increasing pressure from the TV networks to synchronize their schedules to the national live feed, despite no clear timetable for when coaxial cable and microwave relay would reach the Southwest region. For WBAP-TV, this meant “shaking up” its schedule at the end of 1950, shuffling their in-studio content so that the network’s kinescopes (week-delayed episodes of Howdy Doody and The Kate Smith Hour, for example) aired at the same time as the new, live episode aired on the interconnected stations.

By July of 1951, AT&T took the first steps toward a Southwest network extension. The Star-Telegram reported on the installation of an experimental microwave relay to test the viability of picking up a signal from Dallas, while engineers began staking relay station sites between Oklahoma City and Wichita, KS.[7] By September of that year, AT&T officially announced that Tulsa, OK, Fort Worth, and San Antonio would be interconnected to the transcontinental line via Kansas City, MO, open for transmissions “sometime next year.”[8] And by December, Ma Bell’s lineman were laying coaxial cable from Oklahoma City to Amarillo, TX.[9]

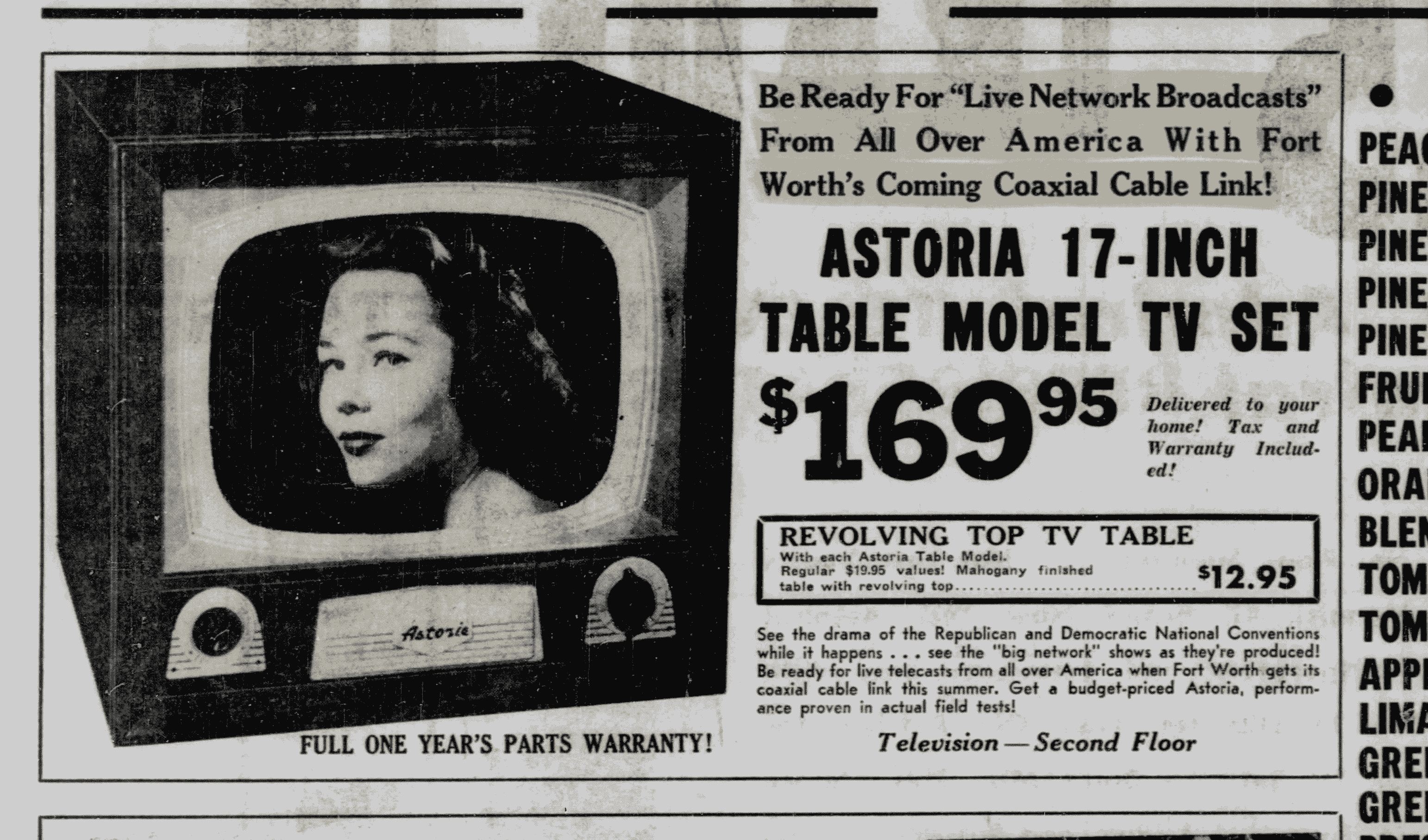

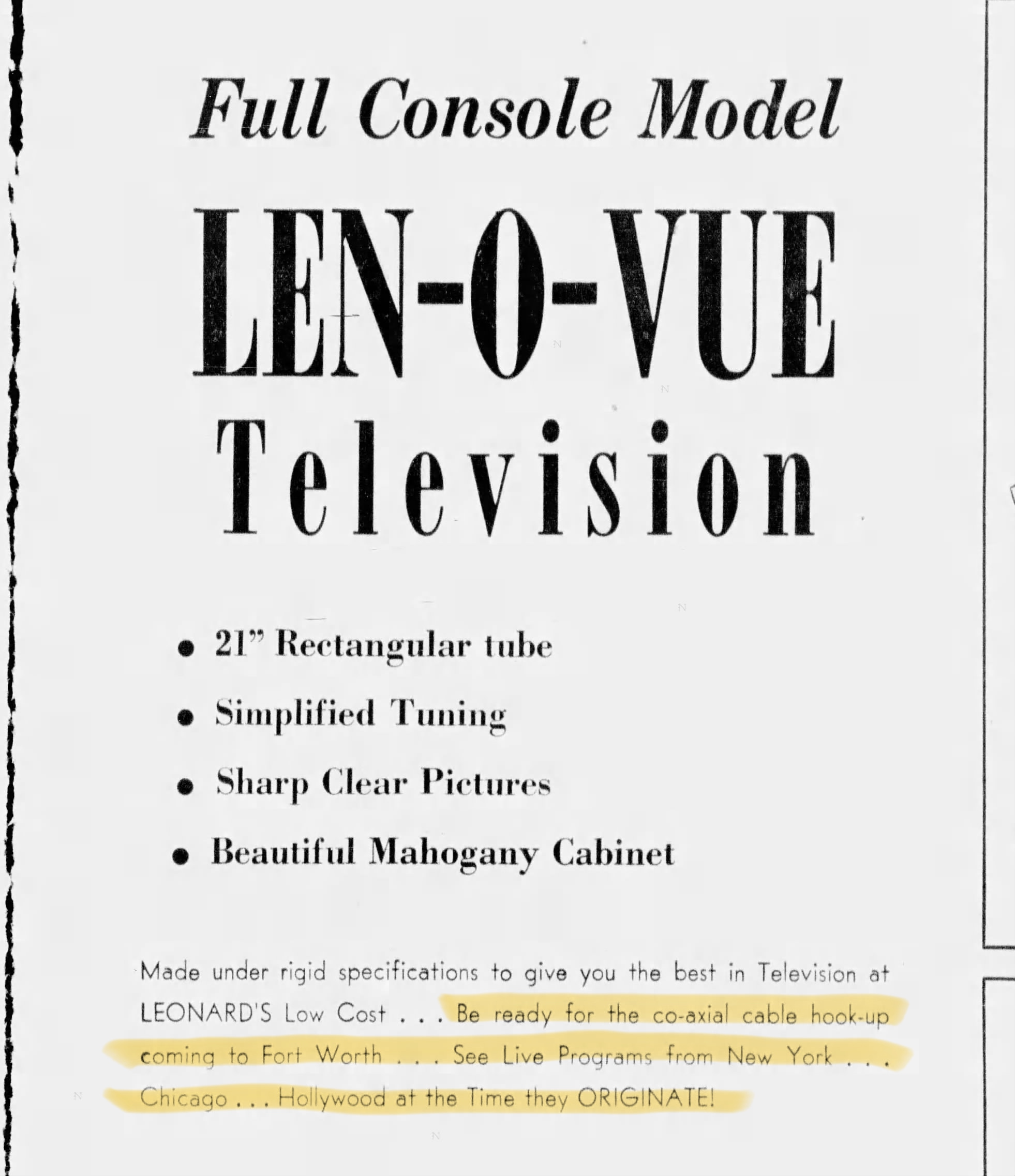

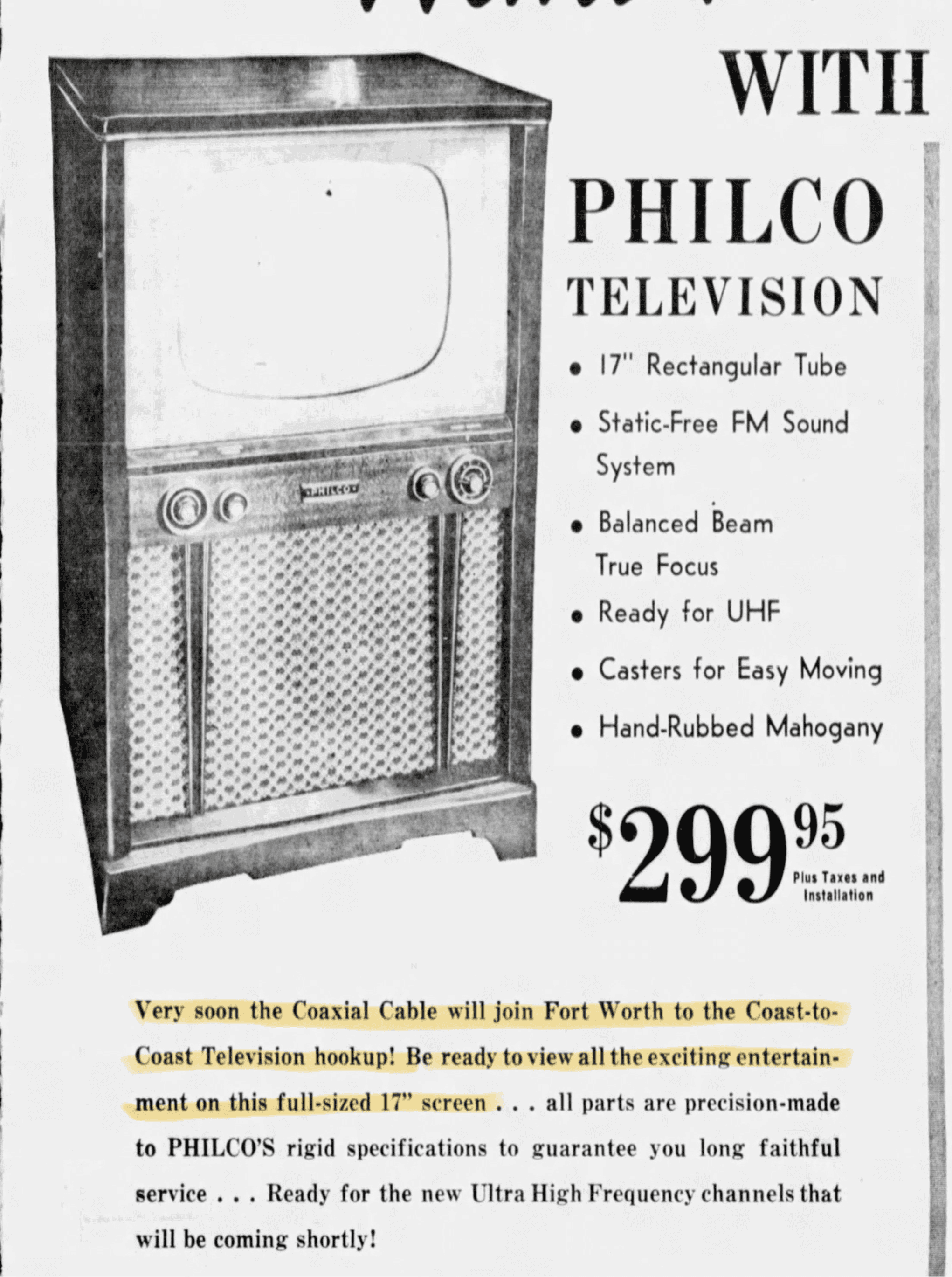

As spring 1952 rolled in, WBAP-TV, local businesses, and the local newspaper began efforts to educate the public. Appliance dealers were especially keen to cash in on interconnection. Not only did they run job classifieds for salesmen so they’d be “ready for the increased business that will come when the coaxial cable is put in operation,” dealers also ran ads for television sets that lured buyers with FOMO appeals.

They even held an “Educational Clinic,” inviting 175-200 dealers to hear a “quartet of nationally known appliance men” discuss “what the coaxial cable’s completion will mean to Texas TV fans.”[10]

WBAP-TV also did its part to drum up excitement. The station aired a “Network Television Is Coming!” special at the end of April, featuring a representative of the Southwestern Bell Telephone Co. who provided a “fascinating non-technical show” with “amazing electronic equipment—in action—which will bring live network TV programs to your screen soon.”[11] And the Fort Worth Star-Telegram published a brief Q&A, answering such questions as “I’ve been hearing a lot recently about ‘live’ network programs. What does that mean—aren’t all the actors ‘live’?”

Finally, in the heat of the Texas summer, with construction complete, WBAP-TV started its July 1st broadcasting day with the first live programming from NBC: at 7 am, the Today show was picked up from NYC, followed by two programs from Cincinnati, and later, the Johnny Dugan Show and the Camel News Caravan from Hollywood.[12] Reports the following morning lauded the clear picture—so clear it “even surprised WBAP technicians, who [had] been watching a test pattern for several days.”[13] Viewers expressed their excitement for even more live content, particularly the upcoming “political conventions, the World Series, and a weekly Saturday football game.” As one article concluded, “Big league television, here at last, is being welcomed heartily.”

However, even with the new link to the network and the possibility of more “big league television,” WBAP-TV’s schedule and its ratio of network-to-local programming stayed surprisingly consistent (percentage-wise, approximately 40:60). Even after AT&T opened an additional coax-microwave relay line nearly a year later, the roughly 118 hours of airtime per week (which had increased six hours from the previous year) was filled with almost 74 hours of in-house and syndicated programming, or, again, about 62 percent.[14]

Which, chronologically speaking, brings us back where we starated: 1953 and the national telecast of the Fort Worth Rodeo.

Along with picking up roughly 40 hours of network programming from the coax live feed, WBAP-TV also made efforts to send out programming to rest of the network affiliates via the AT&T network. Just like Fort Worth viewers had, for example, watched Today synchronously with viewers in New York City, now NYC—as well as Newark, St. Louis, Nashville, etc.—viewers were watching the rodeo simultaneously with Fort Worthians.

Newark’s Star-Ledger wasn’t the only distant newspaper to express enthusiasm. Coverage from as far away as LA praised the telecast—“Phooey to old movies, lets have more rodeos”—while letters from across the country flooded the WBAP-TV desk. “I have owned a television set for many years,” wrote one viewer in Newton Centre, MA, “but never have I enjoyed a show as much as your televising of the Rodeo.”[15] This local-to-national rodeo telecast would happen again the following year, but thereafter, special event programming originating from the Dallas-Fort Worth area became increasingly limited to more mainstream sporting matchups (football in particular). As AT&T’s network grew, so too did the TV networks’ corporate efficiency efforts—e.g., stringent economies of scale, standardization, rationalization.[16] Programming became ever more centralized as it became more nationalized.

This zoomed in analysis of WBAP-TV’s interconnection to the national television networks shows how localized and place-specific that process actually was. Communities and local TV stations had to make sense of this new technology and adapt to its evolving form and distribution logics in ways that were shaped by local geography and culture—for instance, it doesn’t seem to be a coincidence that one of the first national telecasts from Texas was a rodeo; the myth and romance of the cowboy has long signified “Texas” in the popular imagination, and WBAP-TV seemed keenly aware of this.

Television history needs more localized, infrastructural, and cultural analyses. While numerous historians have richly documented early television’s production and reception cultures, far fewer have chronicled the growth and evolution of its distribution systems. And of the few that do exist, even fewer have investigated those systems at the local level.

By excavating these histories, we add nuance to our understanding of early television’s growth and adoption. And we importantly reveal the complex, geographically specific tension between commercial broadcasting’s centralization and differentiation.

Image Credits:

- 1952 Map of U.S. Television Stations and Network Links. Radio & Television News, May 1952, 84–5. Image from RF Cafe.

- 2,100-mile TV ‘Highway’ on Regular Commercial Basis,” Star-Telegram, 12 Jan. 1949, 24 (author’s screenshot)

- WBAP Station Logo. Box 105, Amon G. Carter Papers, Texas Christian University, Fort Worth, TX (author’s screenshot).

- News Clip: Peabody Award and Seesaw Puppet Show, from the KXAS-NBC 5 News Collection at the Portal to Texas History, University of North Texas Libraries.

- Newspaper ads for television sets: “Astoria 17-inch Table Model TV Set,” advertisement, Fort Worth Star-Telegram, March 19, 1952, 12; “Full Console Model Len-O-Vue Television,” advertisement, April 12, 1952, Fort Worth Star-Telegram, 19; “Leonard’s Home Furnishings with a Feeling of Spring!” advertisement, April 18, 1952, Fort Worth Star-Telegram, 7 (author’s screenshots).

- Big Tex at the 2013 State Fair of Texas. Photo by Paul Komarek on Wikipedia.

- Quoted in Ira Cain, “Bouquets Keep Coming for WBAP-TV Rodeo Show,” Fort Worth Star-Telegram, 15 February 1953, p. 14. [↩]

- “2,100-mile TV ‘Highway’ on Regular Commercial Basis,” Star-Telegram, 12 Jan. 1949, p. 24. [↩]

- See, for example, Kathy Fuller-Seeley, “Learning to Live with Television,” in The Columbia History of American Television (Columbia University Press, 2009), 105; Christopher H. Sterling and John M. Kittross, Stay Tuned: A History of American Broadcasting (Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 2002), 287. Sterne provides a fascinating and much more detailed analysis of TV distribution’s infrastructural growth and nationwide televisual simultaneity, and yet still cites 1951 as the year it was achieved. Jonathan Sterne, “Television Under Construction: American Television and the Problem of Distribution, 1926-1962,” Media, Culture, and Society 21, no. 4 (1999), 515. [↩]

- NBC officially used this terminology to delineate stations that hadn’t yet been “wired” into the AT&T network. See S.B. Hickox to Carleton D Smith, 12 December 1949, box 591, folder 33, National Broadcasting Company Records, Wisconsin Historical Society, Madison. [↩]

- Erik Barnouw, Tube of Plenty: The Evolution of American Television (Oxford University Press, 1975), 113. [↩]

- “The stations, having no cable connections, had to be served through a cumbersome procedure of shipping [kinescopes] from station to station. It was called “bicycling.” See Barnouw, 205. [↩]

- Ira Cain, “Tiny Beam from Dallas…” July 15, 1951, Fort Worth Star-Telegram, 30. [↩]

- “TV Network to Southwest Expected Late Next Year,” September 6, 1951, Fort Worth Star-Telegram, 5. [↩]

- “Coaxial Cable Started,” December 7, 1951, Fort Worth Star-Telegram, 2. [↩]

- “One-Day Educational Clinic Arranged for TV Dealers,” May 21, 1952, Fort Worth Star-Telegram, 15. [↩]

- “Be Sure to See ‘Network Television Is Coming’,” advertisement, April 27, 1952, Fort Worth Star-Telegram, 34. [↩]

- “‘Live Network TV Shows Delight Thousands of First Time Viewers Here,” July 1, 1952, Fort Worth Star-Telegram, 1. [↩]

- “Fans Welcome Direct Service over WBAP-TV National Hookup, July 2, 1952, Fort Worth Star-Telegram, 17. [↩]

- Note: I compared television schedules published in the Fort Worth Star-Telegram for the final week of May for three separate years: 1952 (a month before the opening of the first coaxial line), 1953 (approximately a year after the line opened), and 1954 (approximately a year after a second coaxial line opened). While, for the most part, the origination category (“studio,” “NBC,” or “ABC”) for each program was clearly, labeled, there were some unlabeled programs. For these, I did a basic Google search of the program’s name to determine whether it was produced or licensed at the local level or whether it was a network program. If no useful information was available, I made a good-faith assumption and categorized accordingly. [↩]

- Ira Cain, “Nothing but Highest Praise Heard of WBAP-TV’s Networking of Rodeo,” February 8, 1953, Fort Worth Star-Telegram, 36. [↩]

- For a history of broadcasters’ evolving standardization practices, see Randall Patnode, The Synchronized Society: Time and Control from Broadcasting to the Internet (Rutgers University Press, 2023). [↩]

Just pure brilliance from you here. I have never expected something less than this from you and you have not disappointed me at all. I suppose you will keep the quality work going on.