So Why Did Everybody Love Raymond?

Kelli Marshall / University of Toledo

Since Everybody Loves Raymond (1996-2005) premiered, critics have compared it to Seinfeld (1989-1998).1 At first glance, this association seems ridiculous given that the characters, structure, and themes of the two sitcoms ostensibly have little in common. For example, Seinfeld is a decidedly postmodern program featuring four unabashedly single Manhattanites; it is usually structured via short narrative segments, many self-reflexive in nature, that often interlock to form a tight yet complex whole; recurring themes include casual dating and sex, toilet habits, and political correctness. Conversely, Raymond is a conventional, middle-class family sitcom set in the suburbs; it employs a traditional, uncomplicated three-act structure; repeated topics include sexless marriages, in-law troubles, and sibling rivalry.2

Still, those critics who’ve looked closely at Everybody Loves Raymond and Seinfeld locate several similarities, even suggesting that fans of one program will readily become fans of the other. For instance, both sitcoms center on fortysomething stand-up comedians from New York who lack acting experience and whose comedy is grounded in the mundane observations of daily life. Moreover, both shows are very much ensemble efforts, distinctly ethnic (Italian-American and Jewish), and feature dysfunctional supporting characters “who barge through the door and into [each other’s] chaotic lives.”3 While these conclusions are legitimate — and in hindsight, rather obvious — I’m not sure they are the main reasons that viewers of Seinfeld, roughly 18 million during its heyday, would theoretically gravitate toward Everybody Loves Raymond, which also drew about 18 million during its prime.4 After all, King of Queens (1998-2007), Yes Dear (2000-2006), My Wife and Kids (2000-2005), The Bernie Mac Show (2001-2006) and According to Jim (2001-2009) also incorporated most of the above attributes, but they never had the ratings of Raymond or Seinfeld, not to mention the awards or critical success. Rather, I propose that so many Americans embraced Everybody Loves Raymond because it repositioned yet sustained the qualities that viewers (for better or worse) appreciated in Seinfeld: well-crafted, narcissistic characters suspended in adolescence, a consistent and humorous focus on the minutiae of human existence, and a guiding mantra of “no hugging, no learning.”

In “Seinfeld‘s Humor Noir,” Irwin Hirsch and Cara Hirsch maintain that Seinfeld stands out among sitcoms because its adult characters function as adolescents, celebrate narcissism, and take pleasure in their own venal behavior.5 The four possess no “redeeming, positive, humanistic values,” Hirsch and Hirsch point out.6 Indeed, as all Seinfeld devotees know, Jerry (Jerry Seinfeld), George (Jason Alexander), Elaine (Julia Louis-Dreyfus), and Kramer (Michael Richards) value games over rules of propriety (e.g., masturbation contests, Trivial Pursuit with the Bubble Boy, Kramer’s gambling), break commitments over the smallest flaws (e.g., “low-talkers,” “bad breaker-uppers,” “man-hands,” “Jimmy legs”), obsess over bodily functions (e.g., reading on the toilet, “shrinkage,” nose-picking), scoff at traditional rites of passage like marriage or pregnancy (e.g., “Ugh, it’s been done to death”), and take pride in their emotional barrenness (e.g., George opts for coffee after the death of his fiancée, Kramer giddily videos an obese man who’s being mugged). Ultimately, all of this relentless cynicism and corrupt characterization is encapsulated in Seinfeld‘s guiding philosophy “no hugging, no learning,” i.e., the show will offer no moral lessons, and the characters will never become sentimental with each other.7

Although its setting and characters may have relocated — from Manhattan to the suburbs of Long Island, from singlehood to married life — Everybody Loves Raymond maintains these distinctly Seinfeldian traits. First, like Seinfeld‘s characters, the Barone family approaches life as a game, rivaling each other within their own little dysfunctional “clubhouse atmosphere.”8 While each family member exhibits this trait,9 it is perhaps most evident in the competition that takes place between Ray Romano’s Raymond — a sports writer, husband to Debra (Patricia Heaton), and favorite son of Frank (Peter Boyle) and Marie (Doris Roberts) — and his older brother, Robert (Brad Garrett) — a morose NYC policeman who still lives with his parents and openly resents virtually everything about his younger brother. For instance, the two have competed over the title basketball captain (1.11), a prize in a box of cereal (1.7), their appearances (1.14), gift purchases (2.31, 3.59, 4.84, 7.158), a Civil War reenactment (2.35), a toothbrush (3.55), dancing partners (3.71), the affection of children and future in-laws (5.119, 7.161), their names (6.132), tending bar (9.203), and overall, their parents’ attention. The brothers have also fought physically, wrestling each other to the ground like spoiled children because Robert’s promotion to lieutenant garnered more attention than Ray’s simultaneous announcement that he might publish a book (5.103).10

Second, also like Seinfeld, Everybody Loves Raymond scrutinizes the insignificant details of daily life and reveals how such analyses directly and humorously affect its characters. It is now common knowledge that Seinfeld procured the title “a show about nothing” because it created segments and sometimes entire episodes around such typically mundane topics as waiting in line at a restaurant, re-gifting a present, finding a hair on one’s food, and double-dipping a potato chip. In the same way, Raymond regularly makes something out of nothing. For example, episodes unfold around a fruit-of-the-month club (1.1), an engraved toaster (3.59), a can opener (4.76), P.M.S. (4.95), sneezing (5.107), choking (5.109), a vacuum cleaner (5.115), the wrong brand of Kleenex (6.135), sighing (7.154), the placement of a suitcase (7.196), tardiness (8.185), eating habits (8.189), and smoking (9.209).

Finally, not unlike Jerry et al, the Barones refuse to “hug” or “learn,” consistently shooting down moral lessons and possible moments of genuineness with insensitive or spiteful dialogue.11 For instance, in “Jealous Robert” (6.129), Frank recounts how, when he was younger, he was so envious Marie cooked for another man that he “punched the headlights off of [the guy’s] car” and then “spent the night in the hospital, picking glass out of [his] arm.” Here, the viewer seemingly believes that even the most hardened, unemotional man once had strong feelings for his wife. But this notion is quickly shattered with the next exchange:

Raymond: Wow, dad, I never thought there was a story like that behind you and mom. It’s almost romantic.

Frank Barone: Yeah, I know. I don’t tell that story a lot.

Ray Barone: How come?

Frank Barone: Because it doesn’t have a happy ending.12

Similarly, in “The Plan” (7.165), Robert and his fiancée, Amy (Monica Horan), reconcile after fighting over misspelled wedding invitations. Before the entire Barone clan, Amy confides, “Robert and I are getting married, and I want us to be honest and trusting. […] I want to get married because I know how great it can be. Maybe it isn’t easy, but I think it’s worth going for.” Robert lovingly concurs, and then the couple exits, leaving the viewer with a potential lesson about love, marriage, and forgiveness. Yet within seconds, that message is cut down with Debra’s dialogue, “Wow. Remember when we were that stupid?” The frame fades to black.

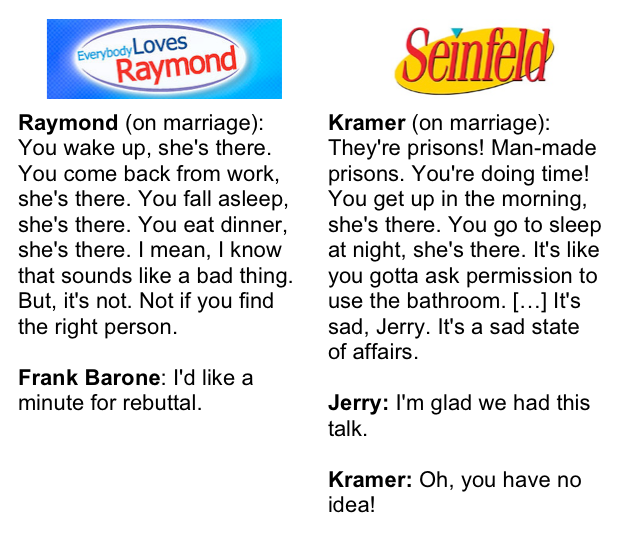

One of the most interesting uses of Seinfeld‘s “no hugging, no learning” mantra is found in “The Lone Barone” (3.56), an episode in which Ray vents to Robert how miserable married life can be, e.g., waiting “all day for Debra’s damn curtains” to be delivered, being “held hostage, trapped inside all of these walls,” being “happy as she lets me be, sleeping when she lets me sleep, eating when she lets me eat,” and finally, seeing the movie she wants to see, “the one where the mother has the disease and the daughter who learns to care about the mother who has the disease.” When these declarations (allegedly) cause Robert to break up with Amy, Ray is forced to reexamine married life and deliver a revised speech. Here it is, paired with a similar one from Seinfeld:

The resemblances here are uncanny. Not only does some of the language match word for word, but also the (long-standing) philosophy that marriage is a prison and that once a man enters it, he is never alone or allowed to do what he wants to do. Indeed, married life can be, both shows argue, “a sad state of affairs.” No hugging, no learning.

One reason that this family sitcom gets away with such traditionally non-familyish qualities is that the Barone children (played by real-life siblings Madylin, Sullivan, and Sawyer Sweeten) rarely appear; they are usually, one critic notes, “tucked out of sight, leaving the adults to have at each other.”13 This setup differs dramatically from similarly constructed family sitcoms of the last couple of decades like Family Ties, Growing Pains, Full House, The Cosby Show, and Home Improvement — series in which “the situation was typically a problem involving one of the children” and the parents would “guide the child through a solution, providing a moral lesson along the way.”14 But again, this break from the norm is probably something viewers of Raymond should expect. After all, despite its surface appearances and traditional three-act structure, Everybody Loves Raymond is not like other family sitcoms. Rather, its juvenile characters with virtually no redeeming qualities and its almost complete rejection of moral lessons place it closer to its predecessor and short-lived contemporary Seinfeld than those which featured the always loveable Bill Cosby or Tim Allen.

Image Credits:

1. Cast Promo Shots of Everybody Loves Raymond and Seinfeld

2. George undergoes “shrinkage”

3. Jerry’s date grips him with “man hands”

4. Robert and Raymond engage in literal game-playing

5. All hell breaks loose over a new can opener

6. Image by author

Please feel free to comment.

- Warren Berger, “Looks Like ‘Seinfeld,’ But Call It ‘Raymond,’ New York Times (1 Feb. 1998): AR41 (ProQuest); Neal Gabler, “Loving ‘Raymond,’ A Sitcom for Our Times,” New York Times (21 Oct. 2001): AR30 (ProQuest); David Wild, “The Cult of Ray,” Rolling Stone 17 Oct. 1996 (Academic Search Premier); Peter M. Nichols, “Raymond Is Loved. What’s Not to Love?” New York Times (17 Nov. 1996): TE3, (ProQuest); Bret Watson, Entertainment Weekly (13 Dec. 1996): 34; Tom Gliatto, “Picks and Pans: Everybody Loves Raymond,” People 46.11 (9 Sept. 1996): 14. [↩]

- Gabler describes Raymond’s three-act structure as a “roundelay of rationalization, recrimination, and remorse.” For example, Ray begins the episode doing something “juvenile or selfish or both.” Then, he attempts to defend himself to his wife or other family members. Finally, Ray’s “guilt sets in, and the remorse, but only very occasionally the wisdom.” [↩]

- Nichols; Berger. [↩]

- Ratings for Raymond and ratings for Seinfeld. [↩]

- Irwin Hirsch and Cara Hirsch, “Seinfeld‘s Humor Noir: A Look at Our Dark Side.” Journal of Popular Film & Television (Fall 2000): 116-123. [↩]

- Ibid, 123. [↩]

- On Larry David’s cardinal rule “no hugging, no learning,” see Lisa Schwartzbaum, “Much Ado about Nothing,” Entertainment Weekly 9 (April 1993); Albert Auster, “Much Ado about Nothing: Some Final Thoughts on Seinfeld,” Television Quarterly 19 (1998): 24-33; and Matthew Bond, “Do you think they’re having babies just so people will visit them? Parents and Children in Seinfeld” Seinfeld: Master of Its Domain: Revisiting Television’s Greatest Sitcom, Eds. David Lavery and Sara Lewis Dunne, New York: Continuum, 108-150. [↩]

- Hirsch and Hirsch use this phrase to describe Seinfeld‘s locations, Jerry’s apartment and Monk’s Cafe, 119. [↩]

- Other family members compete as well. For example, Ray and Debra battle over who is the better test-taker (1.4), children’s-book writer (2.30), checkbook-balancer (2.38), gift-giver (5.108), and disciplinarian (7.162). Frank challenges Ray to ping-pong (3.60), and Marie sabotages Debra’s food just so she can remain the favorite matriarch (2.37). Furthermore, Ray pits himself against his more sexually active father (4.77), Debra’s attractive aerobics teacher (4.78), his daughter’s outspoken Girl Scout leader (6.137, 7.166), and an annoying 8-year-old kid (7.155). Finally, the entire family tries to one-up each other over about which member is the angriest (6.123), the worthiest to represent them in a Christmas-letter (6.134), the most fun (6.136), the best marriage counselor (8.175), the best liar (8.178), and the most religious (7.164). [↩]

- Also like Jerry, George, Elaine, and Kramer, Raymond‘s characters engage in general juvenile behavior. For instance, Debra dumps food on Raymond’s crotch (1.4); Ray wants to keep an old rundown car only because he “got lucky” in it (1.15); Ray, Robert, and Frank devour an entire chocolate cake before Marie catches them (3.52); Ray places a blow-up clown in the bed so Debra will have something other than him to cuddle with (3.67); Frank uses Ray’s sports insight to gamble (4.76); Raymond tapes a football game over his and Debra’s wedding (4.89); and Robert is gored by a bull (4.88). [↩]

- A handful of shows do not subscribe to this “no hugging, no learning” motto. Most of them are season finales, which are often told via flashbacks (e.g., Ray and Debra’s wedding, the birth of their daughter, etc.) and usually take on a slightly more sentimental tone. [↩]

- Later in “Robert’s Jealous,” Frank still fumes that he let Marie’s food get the best of him (and his jealous nature) so many years ago: “Chuck Pacarello [the man for whom Marie was cooking]. Where the hell is he? That son of a bitch owes me. I’m serving his life sentence! [↩]

- Berger. [↩]

- Richard Butsch, “A Half Century of Class and Gender in American TV Domestic Sitcoms,” Cercles 8 (2003): 16-34. [↩]

Pingback: Everybody Loves Raymond and Seinfeld | Unmuzzled Thoughts (about Teaching, Shakespeare, and Pop Culture)

Kelli, I think you make some interesting and purposeful links between the two series, but I tend to resist the notion that these connections would result in a logical audience shift from one to the other; on the contrary, I think that the context of each series’ characters and actions are diametrically opposed. The same people who enjoy single people being horrible to one another may find it garish for a family to do the same, and those who are able to enjoy Seinfeld irreverence may balk at the same sorts of traits being mashed together (to my mind, as we’ve discussed in the past, unsuccessfully) with the family sitcom mold. The two series may engage with similar ideas, and those ideas may occasionally appear similar on the surface, but the reasons they are being deployed seem very different for me.

If you were to show someone who had no knowledge of either show a scene from each, I do think that they could engage with similar issues within both (the marriage scene is a fine example of that), and there’s certainly value to isolating them in order to discover how two very different shows are playing with similar ideas. However, I don’t think that regular viewers can so disassociate Raymond from its fairly traditional sitcom feel that it becomes synonymous with the far more subversive structure of Seinfeld, nor can they ignore how Seinfeld became the center of a cultural zeitgeist and Raymond became a show which skewed old and was the antithesis of hip.

I have no doubts, just so we’re clear, that Raymond has its fans and its place: I just think that the Seinfeld comparison reduces the series to basic qualities which were at times unseen amidst the context of the series’ broadcast, and I don’t think that we can minimize that reception within the discussion when viewer opinion is involved.

Hi, Myles!

First, thanks for reading and for the comments. Second, I have to say that I’m a bit surprised at the extent of your remarks since I know (from previous discussions) that you’ve watched very little of either series. =) With that said, I’ll still bite…

You write that a comparison of Raymond to Seinfeld “reduces the series to basic qualities which were at times unseen amidst the context of the series’ broadcast.” I’m not sure why you would conclude that Raymond‘s qualities — I’m assuming you mean juvenile, narcissistic characters, no hugging no learning, etc. — were “unseen” during the show’s original broadcast. Several critics, fans, message boards, etc. pointed to these traits while the show was on the air — just as they pointed out the similarities between it and Seinfeld.

I’m also a bit confused by your claim that Raymond “skewed old and was the antithesis of hip.” Re: hip, maybe; but skewing old isn’t correct. In fact, Raymond was ranked highly among the networks’ target audience, 18-49 year olds (I had several links here, but Flow said I was spamming). Moreover, the series currently attracts the same age group in syndication on TBS.

I think something else we might ought to consider re: Raymond and Seinfeld is that many who watched Seinfeld during its heydey were single, youngish Gen-Xers (like myself and my friends who still quote the show to this day). But when it went away (and Raymond hit its prime), many of these audience members (like me) had grown up, become professionals, married, moved to the suburbs, etc. As a result, in Raymond we found many of the same qualities that we appreciated (for good or bad) in Seinfeld.

Pingback: Why I want to revisit WKRP in Cincinnati « Feminist Music Geek

Pingback: Those Gene Kelly Volkswagen Commercials Suck, and Here’s Why | Unmuzzled Thoughts

Pingback: Everybody Loves Raymond and Seinfeld | Pop-Cultured Prof | Kelli Marshall

Pingback: Those Gene Kelly Volkswagen Commercials Suck, and Here's Why | Pop-Cultured Prof | Kelli Marshall

Before reading this article whenever I watched Everybody Loves Raymond I would never think that it was a similar show to Seinfeld. Everybody Loves Raymond is a suburban family sitcom while Seinfeld focuses on the lives of friends living in the city of Manhattan. One major statement that I read in the article that made the shows a lot more similar is when Marshall says “One reason that this family sitcom gets away with such traditionally non-familyish qualities is that the Barone children rarely appear; they are usually, one critic notes, “tucked out of sight, leaving the adults to have at each other.” After I read this I thought back at all the episodes and realized that probably only one or two of them focus on the kids problems. The only time you see the kids in many of the episodes is when they are playing in the back ground or used for the adult characters to do something funny with them. I feel that this totally takes Everybody Loves Raymond out of the classic family sitcom genre. Unlike shows such as Home Improvement or The Cosby Show that usually had plots evolved around the children having problems and the adults helping them overcome them, Everybody Loves Raymond had similar plots to shows like Seinfeld.

I feel that is why Everybody Loves Raymond became as successful as Seinfeld because it was sort of a family sitcom, but mostly focused on adult issues in a funny way. The shows would poke fun at the small things in life, such as opening a can opener or fighting over a parking space, and then evolve the rest of the show around that. That is why these two shows became so popular because they took something so simple that the audience could relate to and made it funny.

Pingback: Comic Conversations and Jerry Seinfeld’s Comedians in Cars Getting Coffee | MediAcademia

I’m a bit late, but this is a nice comparison. I was a fan of Everybody Loves Raymond, and found later that I enjoyed Seinfeld as well. I agree with Kevin that what makes the shows fun and entertaining is that we can relate to them.

btw, as for the critic who made tho comment about the kids being tucked away. This is not news. this is a premise of the show. in the opening credits for the first season, Ray introduces his kids and says, “it’s not really about the kids.” lol. absolutely right! the kids make very little appearance. only appearing when it gives the adults a problem. and can I say the only episodes that really focused on the kids are the ones I don’t really care for (it’s supposed to be fun, party dress, etc.) those episodes have redeeming qualities, but they break from the usual pattern of the show. even in the hug and learn rule.

Very nice article. :)

seinfeld has a wildean sense of absurdity at its core

raymond – is an utterly sincere – and suitably tortured – investigation of the question of whether our basic values can survive the ordinary ethical challenges of everyday family life.

you are confusing an absurdist world view (on which the only things that could possibly matter are the tiny tiny everyday things we all treat precisely as insignificant)

with a common-sensical world view (the one that’s implicit particularly in our family lives – in which kindness is better than cruelty and we should all try to be straight with each other at least most of the time) – a common sense world view beset by the profoundly genuine worry that our commitment to the common sense values that are the conceptual foundation of family life (love don’t hate; protect and support don’t threaten and attack) – is a commitment based on illusions, something that cannot survive honest confrontation with the detail of everyday family life. so on one picture (seinfeld) we’re shown that what people think matters doesn’t (and maybe what they think doesn’t does – but only because its so silly); on the other we’re shown that maybe we’ll be able to be decent in and through our families, and maybe we won’t; we’re reminded both of how deeply we are committed to a set of basic moral values (in virtue of being children, brothers, fathers, husbands, mothers-in-law etc.) and how uncertain we must be about whether that commitment makes sense. on one picture we know that life is ultimately senseless; on the other we assume that it makes sense but worry endlessly that we are wrong to do so.

i adore seinfeld – but raymond is massively better – more significant, more honest, more challenging to watch. for raymond and debrah pain and protracted distress are still real possibilities – for kramer and george they were never on the cards (‘Great! i always wanted to pretend to be an architect!’ – that person can have no fear that the traditional values will devalue themselves. for seinfeldians that has already happened – its old news.

Beautifully said Jon

I am amazed that this show is often overlooked by stupid aesthetes

And misunderstood

In many ways it is the most radical sitcom made to date

Everybody Loves Raymond is a boring, plodding and completely predictable sitcom that is no different to what came before (or after) it. It has dated badly.

Seinfeld was cutting edge for its time (and still remains fresh to this day), and remains very watchable.

Comparing the two is ridiculous, its like comparing dog food and filet steak!