Fiercely Real? Tyra Banks’ Body Politics and Post-Feminist Branding

Jessalynn Keller / Flow Special Features Editor

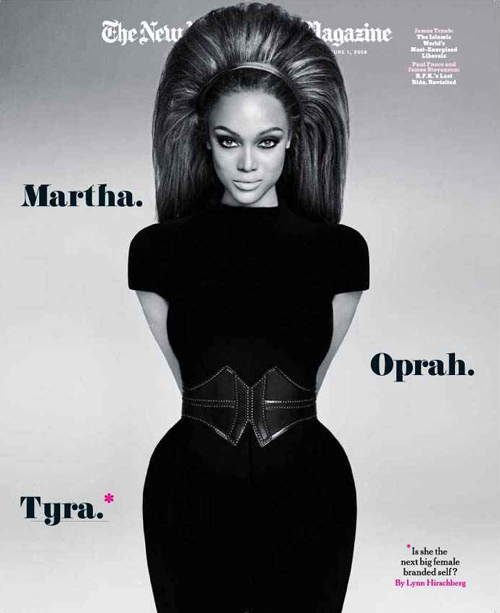

The simple black and white cover of the June 1, 2008 issue of the New York Times Magazine says all you need to know about today’s Tyra Banks. The former supermodel-turned-business savvy media mogul looks straight at the camera, her waist cinched by a thick belt, revealing her curvy figure. The words on the page are stark: “Martha. Oprah. Tyra.*” And then at the bottom of the page: “*Is she the next big female branded self?” Look around contemporary popular culture and it would be difficult to disagree.

While Banks has been a staple of American media culture for close to two decades, it is her recent shift from television personality to multi-media brand that I want to investigate. In late December 2009 Banks publicly announced that she would be leaving her Emmy-winning afternoon talk show The Tyra Show to pursue the development of her film company Banksable Productions. Industry insiders have revealed that Banks plans to shift her attention to movies in order to “bring positive images of women to the big screen.”1 This attention shift also sees Banks develop an extensive online presence through her recently relaunched website, Tyra.com, where she has spearheaded her Beauty Inside Out (B.I.O) campaign. This campaign has become a key component of her current branding strategy, which centers on the body as a site for both power and self-esteem for young women.

Tyra Inc.

Having first gained popularity as a sultry supermodel in the mid-1990s, Banks’ celebrity persona developed within the climate of neoliberalism and promotion of color-blind rhetoric and post-feminist notions of gender. Perhaps ironically though, Banks became popular in part because of her positioning as a raced and gendered body. She was the first black model to grace the covers of Sports Illustrated Swimsuit Issue, GQ, and the Victoria’s Secret catalogue. But while her body earned her the status of a pioneer in the modeling world, Banks has always maintained – and continues to reiterate through her role as host and judge on her successful reality television show America’s Next Top Model – that it was her resiliency and work ethic that earned her mainstream success.

While Banks has credited a ‘strong work ethic’ as essential to her career, it has always been her promotion of her body as brand that has dominated her marketing strategy, even after retiring from modeling in 2005. In particular, Banks’ breasts have become “a major signifier of the Tyra brand.”2 Her “booty” has also become somewhat prominent in her brand identity since a 2007 episode where, after a tabloid magazine called her fat, Banks retorted defiantly on her talk show, telling “all those who have something nasty to say to me or other women who are built like me: kiss my fat ass!”

[youtube]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6mOQh3evqsI[/youtube]

Banks’ Tyra.com website reveals how she has utilized her brand identity to reframe her public mission as a crusader for both positive media representation and self-esteem for young women. This new mission is also indicative of her shift from a post-2005 television personality to 2010 multi-media celebrity, with her brand now extending beyond television and into both the Internet and film.

Banks launched her Beauty Inside Out Campaign in fall 2009, along with her rebranded website. The first initiative of the campaign was the “Fiercely Real” teen modeling competition, which was limited to “plus size” teenagers who would compete on Banks’ talk show in order to win the title of the “Fiercely Real” model winner, a modeling contract, and a photo shoot with Banks. On her site Banks writes that “the term ‘Plus-sized’ models sounds super old fashioned…so I’m changing the term ‘Plus-sized and making it ‘Fiercely Real’!” The pictures from the final shoot were posted on Banks’ website and the first Fiercely Real winner, Sheridan Watson, a “17 year-old, size 14, fierce teen from New Jersey” was “crowned” in March 2010.

From the outset, Banks’ B.I.O. Campaign appears to be a progressive, feminist approach to body image and media representation. After all, feminist research has demonstrated the harmful effects of unrealistic media images on the confidence of girls and women.3 However, Banks’ mission is clearly a corporate one. In her discussion of the ‘Fiercely Real” competition she writes, “It’s my mission to expand the definition of beauty. To show unique, atypical, fiercely real, quirky, clumsy, five-headed girls through all of my many media projects and businesses. So watch out for what I have in store next!” While Banks does invite girls to make a “B.I.O. pledge” as to how they’re going to rally against “unrealistic” media images, Banks’ project appears to be more about her own brand identity and her “many media projects and businesses” than about feminist politics per se.

This becomes particularly evident in the language that she uses to discuss the campaign. There is a glaring absence of any reference to feminism or the long history of work by feminists to combat unrealistic images of women and girls in the media. There is also no mention of the many organizations throughout the United States and the world that are currently lobbying for more positive representations of women not just in terms of body size, but also in terms of race, ethnicity, sexuality, class, ability, and other identities. While it would make sense for Banks to use the connectivity that the web offers to link to other related feminist projects with the hopes of forming a broad coalition of media activists, she specifically chooses not to. Thus, Banks’ project exists in isolation from feminist media activism and is instead represented as the brainchild of Banks as an individual mentor and businesswoman.

Banks continually utilizes the words “fierce” and “real” throughout her discussions of the B.I.O. campaign. The word “fierce” is an interesting choice for several reasons. While Banks has appropriated the term within the past few years, using it frequently on America’s Next Top Model to describe something particularly outstanding, the word has a longer history within marginalized communities. It was originally used in queer communities and in particular, was taken up by queer people of color, such as the FIERCE organization for LGBTQ youth of color in New York City.4 It was integrated into the fashion industry, primarily by gay men of color, such as America’s Next Top Model judge and runway coach Miss J Alexander, where it became mainstream.

Considering its history as a word from the margins, Banks’ reliance on “fierce” raises several interesting implications. First, it potentially alludes to her own marginalized position as a black woman in a media industry dominated by white men, as well as the marginalized position of her “fiercely real” sized teen models in an industry dominated by thin, white women. Second, it potentially allies her with the queer community, where she has been recognized with the 2009 Excellence in Media Award from the Gay & Lesbian Alliance Against Defamation (GLADD). She also employs several openly gay men on her America’s Next Top Model team, as well as has featured several lesbian and one transgendered contestant.5

But despite the potential spaces to challenge dominant white heterosexual norms with which the word ‘fierce’ carries, Banks refuses this opportunity. Instead, she empties the word ‘fierce’ of its political context, while promoting a very stereotypically white, feminine gender performance in the B.I.O. campaign. For example, in March 2010 Banks writes on Tyra.com that, “This week is all about being natural. Real. The real you.” She continues to instruct her visitors,

You see the pictures on the cover this week? I’m barely wearing any make-up and I got the real hair goin’ on (with a relaxer of course). Sometimes you just need to let go, have fun, and show those freckles… Of course I don’t expect you to go to school or work with no make-up, but maybe on a Saturday out to the grocery store you could keep your fresh face and just add some clear lip-gloss! … Fierce & Love, Tyra

Banks’ suggestion to “add some clear lip-gloss” may send the signal to be more natural, but it also implies the importance of still being adequately feminine. Additionally, it still assumes and requires that one has clear lip-gloss, that it is part of every girl’s make-up essentials. Furthermore, her disclaimer that of course she doesn’t “expect you to go to school or work with no make-up” maintains traditional ideas about feminine beauty – that in the formal public sphere, women must still be clearly feminine.

Despite Banks’ rhetoric about loving and embracing your “real” body, Banks is known for always wearing a hair weave and having her hair relaxed. Her comment above, that she’s “got the real hair goin’ on (with a relaxer of course)” indicates that her hair relaxer is a non-negotiable, an assumed part of her “real” beauty. But while Banks’ hair discourse is clearly about issues of race and beauty, Banks refuses to frame it as such, instead positioning her hair relaxing as a personal choice, equivalent to putting on lip-gloss. Thus, Banks’ beauty discourse remains within the neoliberal post-race project, where black women are entitled to choose to whether to relax their hair, divorced from the broader political and social implications that this decision may imply.

Banks’ B.I.O. campaign relies on neoliberal discourses of choice, empowerment, and freedom in order to promote self-esteem by loving one’s ‘real’ body. This ‘real’ body though remains unquestionably feminine, even if one ‘chooses’ to leave the house sans make-up one day. Furthermore, this empowerment is a personal project guided by Banks’ advice, rather than broader political activism. Thus while Banks makes obvious the ways that femininity is constructed through markers like make-up and hair relaxers she does not undertake a Butlerian analysis of the performative aspect of femininity, instead encouraging her fans to embrace a ‘real’ femininity that nonetheless still relies on normative understandings of gender, race, class, and sexuality.

While Banks considers herself “curvy,” she has always maintained a slim, disciplined body and has required her Top Model contestants to do the same. Banks does have the power to change normative standards of beauty through casting America’s Next Top Model, however, she has yet to actually do so. While most of the models on the show are extremely thin, the odd “plus-size” girl that is featured is often very similar to the thin girls, albeit a few sizes bigger – more of a size eight than a size zero. It is for this reason that I see this Banks’ increased emphasis on “Fiercely Real” beauty as part of a branding strategy that will keep her fans engaged within her various multimedia projects while developing a star text that appears progressive, modern, and non-threatening to her many advertisers, including cosmetics companies like Cover Girl.

From ‘Fierce’ to Farce?

Banks’ latest endeavor raises many questions about the place of beauty and body image issues within mainstream media. While I don’t think that Banks’ Beauty Inside Out campaign is entirely negative, I do think that Banks’ position as a celebrity entrepreneur must be interrogated in relation to this rebranding project. For example, Banks is embarking on this mission at a time when public discourse about body image in fashion is popular, with The New York Times even recently doing a story about the increase use of “plus –size” models in fashion magazines. Furthermore, brands such as Dove have capitalized on their promotion of positive body image through their ‘Real Beauty’ advertisements and skin care products, demonstrating that selling ‘self esteem’ can be successful.6 The promotion of an empowered consumer therefore is an already established marketing discourse that affirms the neoliberal project promoted by Banks. Framed in this way, Banks’ initiative seems more like a bid to keep her celebrity status relevant than to actually become engaged with the complex politics of body image.

I’d also like to suggest that true empowerment for girls and young women must go beyond their physical body. While being comfortable with your body is certainly important it should not be promoted as the ultimate marker of self-esteem or empowerment. Instead we should be telling girls to develop their minds through intellectual, artistic, and athletic pursuits, which offer them skills beyond their appearance. Consequently, Banks’ continual focus on her own body as her source of self-esteem – and the bodies of girls and young women – prevent Banks from undertaking truly fierce work.

Image Credits:

3. Banks with Miss J Alexander

4. Top Model’s only “plus size” winner, Whitney Thompson

Please feel free to comment.

- Thomas, K. (2009). Tyra Banks leaves her daytime talk show. The Examiner.com. Retrieved April 29 from http://www.examiner.com/x-21513-Nashville-Celebrity-Headlines-Examiner~y2009m12d28-Tyra-Banks-leaves-her-daytime-talk-show. [↩]

- Joseph, R. (2009). ‘Tyra Banks Is Fat”: Reading (Post-)Racism and

(Post)Feminism in the New Millennium. Critical Studies in Media Communication 26 (3), 237-254. [↩] - Bordo, S. (1993) Unbearable Weight: Feminism, Western Culture, and the Body. Los Angeles: University of California Press. Kilbourne, J. (1999). The More You Subtract the More You Add: Cutting Girls Down to Size. In Deadly Persuasion (pp. 128-154). New York: Simon and Schuster. [↩]

- Queers United Blog. (2009). Word of the Gay: Fierce. Retrieved May 8, 2010 from http://queersunited.blogspot.com/2009/02/word-of-gay-fierce.html [↩]

- While increased representation of gay and lesbian people on television is important, the transgressive possibilities of gay representation on Top Model arguably remain limited, as gay men are already assumed to be interested in fashion and style. Thus, Banks is not necessarily challenging stereotypes or transgressing boundaries with queer representation on her show. [↩]

- Dye, L. (2009). Consuming Constructions: A Critique of Dove’s Campaign for Real Beauty. Canadian Journal of Media Studies 5 (1). Retrieved May 4, 2010 from http://cjms.fims.uwo.ca/issues/05-01/index.html. [↩]

This is a very informative article and well written. I agree that on the surface it appears that people like Tyra are going against the status quo. Just looking a bit beneath the surface, one can easily see that media personalities like her are really defending it, their livlihood depends on it.

I think that the audience is more savvy to these facts than some may realize. Everyone knows she is a ‘top model’ and that she enjoys her status as one of the few black models to reach the stellar heights of her industry.

It does make me kind of sad to see even a figure who claims to stand up to the stereotypes and unrealistic bombardment actually succumb to the cycle. It’s all about money in the end, isn’t it. Why isn’t there just one honest person who can forget about making an extra buck and “supporting the industry” and try to actually make a change?

Does she ever talk about the nose job she has clearly had? Just look at earlier pictures and compare. She is a big phony!

Thanks for the suggestions you have discussed here.

Furthermore, I believe there are numerous factors which keep your

motor insurance premium straight down. One is, to take into account buying motors that are from the good report on

car insurance businesses. Cars which can be expensive are more at risk of being snatched.

Aside from that insurance is also in line with the value of

your truck, so the costlier it is, then the higher the actual premium you spend.

You make some excellent and very perceptive points. I wonder how this article could be expanded now considering developments since its publication in 2010. For one, Banks’ investment in a business degree at Harvard University and her subsequent conceptualization of the college edition of America’s Next Top model in the latest cycle seems to both corroborate and challenge your argument. On the one hand, Banks seems to be encouraging young women to pursue the intellectual empowerment you mentioned in your conclusion by seeking out a college degree, insisting that beauty and self-esteem should go beyond physical maintenance.

On the other hand, the way Banks ties in her new degree to the college edition seems to act merely as a way of emphasizing her own brand identity as a media-savvy business woman. With Harvard’s own brand now attached to her name, Banks can further legitimate her role as a corporate leader and envelop academic discourses within her relation to the fashion industry. I wonder still whether this incorporation of the college education element served merely as a gimmick to abate America’s Next Top Model’s declining ratings, something that seems to be suggested also in Banks’ strategy for the new cycle, which will involve both male and female contestants. This is further evident in her restructuring of the show to include fan votes in judging contestants and the firing of iconic past judges. With all this in mind, it will be interesting to see her next move, and to discern to what extent the target audience is aware of Banks’ ever more prominent business/entrepreneurial mentality as she fights to keep her depoliticized media brand alive.