“This Must Be a Bad Movie”: Genre and Self-Reflexivity in Alan Wake

Racquel M. Gonzales / FLOW Staff

A Psychological Action Thriller

More than five years in the making, Alan Wake, a thriller/horror video game, was released May 2010 and immediately praised and derided for its unique experiment in game storytelling and interactive experience In contrast to popular sandbox games like Red Dead Redemption, Alan Wake does not present illusions of open freedom as players virtually embody the title character, a popular crime fiction author with writer’s block searching for his missing wife in the charming-turned-frightening Bright Falls, WA. Hindrances include Wake’s week-long memory gap immediately following his wife’s abduction and dark forces out to destroy him. Wake quickly realize the events within the town and the game are predetermined, sprung forth from pages of Wake’s Departure, a novel that had only existed in his dreams and imagination. The game is not only deeply invested in telling a story, but in exploring how stories are told across media as well as notions of artistic influence, authorship, and reality versus imagination.

Accordingly, the game is greatly structured, which has received its fair share of mixed reception from the highly praiseworthy as revolutionary storytelling to its intense dismissal as boring and predictable. The latter opinions often point to the low target sales as proof the game is a failure. Many players and game studies theorists have historically seen narrative and gaming at odds with one another,1 though even the most stringent ludologists and narrantologists recognize the entanglement of the two. While it is not without flaws, Alan Wake provides a unique opportunity to engage with assumptions about what games should do versus what they can potentially provide us; to be succinct, what do we, as players, want out of a gaming experience? From the popular complaints across the web, it isn’t a game for every gamer, especially those favoring shooters, multiplayer online modes, or game play that provides a seamless illusion of freedom. Instead, what Alan Wake does quite successfully is expose the framework of gaming and horror storytelling, both formally and narratively, through its purposeful, self-reflexive engagement with conventions of other media forms and genres.

[youtube]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Q2YrcfR9mvU[/youtube]

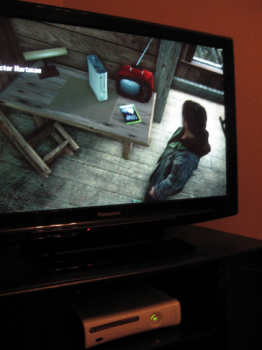

Both within the narrative and game play, Alan Wake actively blurs the boundaries of video gaming and other media by connecting the medium to other storytelling platforms. In doing so, players not only play a game, but experience a meta convergence of forms that acknowledge and reflect storytelling influences on three levels: on the author Alan Wake, on the creators of Alan Wake the game, and those/from gaming and within the thriller/horror genre. The game is quite transparent about its desire to forge these ties between gaming and television, cinema, radio, and the novel. Rather than the typical gaming structure and a definite conclusion, the game is broken up into six episodes with a cliffhanger ending, offering new downloadable installments available through Xbox Live. Ending sequences and “Previously on Alan Wake” cut scenes mimick a television format. Moreover, the marketing leading up to the game’s release included live action episodes of Bright Falls, a prequel to the events of Alan Wake. Within the game narrative, players can watch Night Springs, a Twilight Zone-esque series whose three minute episodes highlight the game’s concerns with dreaming and reality. But Night Springs is not merely a pop nod to Twilight Zone as players find out Wake wrote an episode as his first professional writing gig and has writing plans for future episodes, thus integrating it’s appearance in the world of Bright Falls. Players may also stumble across the Night Springs board game, an medium acknowledged as a predecessor to video gaming itself. The most reflective media reference highlights the game within a game: Night Springs, Xbox 360 video game, alongside the console itself.

Many critics, including Seth Schiesel of The New York Times, shake their heads at Alan Wake for being clichéd, badly ripping off Stephen King, and trying to be an “eerie TV show.”2. Respect to subjectivity and opinion aside, perhaps Alan Wake is not attempting to hide these connections and subsequently failing to cleverly cover their tracks. In fact, the game seems to be addressing the system of genre influences and expectations at work both within and outside itself. Cinematically, the game utilizes the popular suspense/horror shot of the bad guys creeping up on the ignorant victim by frequently featuring a third person POV shot of the Taken emerging from hidden corners. But within the game, players may experience a dual affect response of watching as a spectator while a Taken sneaks up on Wake and the subjective position of being personally (though virtually) attacked and needing escape as Wake, the character being played. The game’s ludic dodge move heightens this affect by creating tension through slow-motion display of game movement. As well, the need to check behind is both a typical response of horror genre characters as well as a necessity while playing any shooter games where AI enemies can lurk behind corners and behind a gamer’s POV. In another fashion, the radio broadcasts of Bright Falls personality Pat Maine provides back story and context of Bright Falls for players while featuring surprisingly fitting music. After a failed run-in at the radio station, Maine apologies on-air to Wake, wishes him luck, and plays “Black Night” by Charles Brown, a song lamenting a sweetheart being gone and troubles that never end while Wake/the player evades the police and the Taken on the search for Alice, his abducted wife. The soundtrack itself provides fitting mood and thematic music like the Episode One ending track, Roy Orbison’s “In Dreams”, while conjuring up similiar musical soundtracks in fellow genre media like Twin Peaks and The X-Files.

[youtube]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oquUGxmw5Fk[/youtube]

Moreover, the game makes popular genre references to ease players into the story while thematically showcasing the blurred lines between reality and fiction, made even more layered as presented through a video game. Alan Wake relies on player familiarity with the horror/thriller genre, Stephen King, and Lovecraftian-inspired work, particularly John Carpenter’s In the Mouth of Madness whose author Sutten Cane finds himself in similar circumstances to Wake. While there is pleasure in recognizing these narratives and motifs, players also learn these are Wake’s own artistic influences, weaved into his manuscript which we play through in the game. Our self-awareness of these motifs are also recognized by non-playable characters and Wake’s own self-reflexive voiceover commentary. FBI agent Nightingale dismisses Wake as H.P Lovecraft, Raymond Chandler, or Bret Easton Ellis throughout their encounters. Wake’s agent Barry Wheeler describes much of Bright Falls’ chilling experiences in past horror film plots and devices. As for Wake, he references King as an early influence in voice-overs, crediting him for teaching “No one is safe in a good horror story, not even the protagonist,” a fitting description for the game itself. And quite frequently, Wake comments on the way things are suppose to be and how the story should go, self-reflexively considering the modes and conventions of horror/thriller storytelling as a whole.

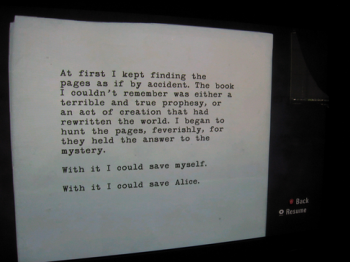

Perhaps most significant is the game’s focus on authorship and control both in its attention to Wake’s writing and the greater aspect of game design and freedom. Players find the manuscript pages of Wake’s completed Departure scattered throughout the game landscape. They provide important clues and sometimes hilariously uncomfortable foreshadowing. For example, following the objective “Make it through the woods,” players can come across the page “Wake Hears a Chainsaw” which reads: “I was finally out of these woods and things were looking up. That’s when I heard the chainsaw”—an event that has not yet happened to Wake/the player, a twist on dramatic irony. The game narrative is centrally focused on the power of Wake as an author since his manuscript controls the events and people of the town. At its core however, the game exposes the control of the game author and designer in limiting the actions and freedom of players. We have very little control over game direction just as Wake has limited control over his own story, having no memory writing it. Both are made transparent while playing. For example, when attacked by Taken with his wife’s kidnapper, Wake demands for a gun and is told “That’s not how this goes, get with the program Wake!” Frustratingly, both Wake and the player as Wake are forced to protect themselves only with flares and a flashlight. Likewise, the kidnapper laughs at Wake for not recognizing the limitation of his abilities as demanded by the story. This constriction mirrors the frequent predicaments of horror protagonist who have to deal with unexpected and outside actions and events rather than he or she thrusting the action. The limitation is also reflective of player frustration for many video game boundaries. With its guided game play, Alan Wake reminds players that video game direction is ultimately determined by someone and something else already in play and outside their control. We are merely players indeed.

My deeper fascination with Alan Wake revolves around the unique affective experience of watching Wake and being Wake. Horror is arguably the most affective genre of storytelling and made all the more (potentially) potent through an interactive game. At times, my reactions to in-game events mirrored Wake’s own “What the hell?” while other moments provided dramatic irony. Often, my desire for safe escape was strangely paired with my hopes for Alan Wake’s escape from the Taken. This dual positionality of watching and being is an often overlooked element to video gaming, but Alan Wake purposefully highlights the position. This draws attention to players and the avatars they play as well as our own relationship with games and more broadly, the stories we engage. This self-awareness is most chilling when we are Wake and we watch Wake view himself on television while the TV’s Alan Wake watches us as the above screen captures eerily reveal. In a flashback, Wake watches himself on TV during an interview for his previous book release The Sudden Stop. Gamers, playing and watching Alan Wake on their TV sets, can watch/play Wake watching himself on his own TV–possibly the most surreal, self-reflexive, voyeuristic moment in the entire game. The live action captures of TV Alan Wake and the Night Springs episodes clearly contrast the computer animated surroundings of Bright Falls, allowing an interesting pairing of the “real” and the simulated deserving deeper attention. Ultimately, the game may not be fiscally successful, but does present a truly distinctive exploration of storytelling and the horror/thriller genre influenced by, but separate from other media. Alan Wake does not need to be the future of gaming to provide another important perspective on what games can do and the larger themes the medium can interrogate in an affectively different way.

Image Credits:

1. Alan Wake Title

2-7. Author Provided Screen Captures.

Please feel free to comment.

- Juul, Jesper. “A Clash between Game and Narrative.” November 1998. http://www.jesperjuul.net/text/clash_between_game_and_narrative.html [↩]

- Schiesel, Seth. “A Game That Thinks It’s an Eerie TV Drama.” May 19, 2010. http://www.nytimes.com/2010/05/20/arts/television/20wake.html?scp=1&sq=alan%20wake&st=Search [↩]

so sweet

indeed its an amazing movie

I love this movie and am looking for movie links now.

Thank you so much for sharing! Great things!!!