Distributing Streaming Content to India’s “Neomobile” Audiences

Rahul Mukherjee / University of Pennsylvania

There is growing research about how Video on Demand (VoD) is adopted and negotiated in non-Western contexts where global and local VoD platforms compete and collaborate with one another. Much of this scholarship emerging out of India, Turkey, Mexico, and South Korea has focused on localization attempts of Netflix and Prime Video in these countries, the distinctive storytelling decisions that guide commissioning practices, and audience insights about local and global streaming services and the “new” content they offer.[1] I will provide some ethnographic vignettes and theoretical insights on this moment of churn (or transition) in the Indian media industry brought by VoD streaming services. Instead of production processes, my focus will be on distribution practices with attention to how multiple intermediaries and actors like content curators and content delivery networks (CDNs) who work at different points of the streaming distribution supply chain think about optimizing and targeting delivery of content to new mobile phone audiences, often called “neomobile” audiences. Mobile phones for this emerging group of VoD consumers are often the one and only device through which they watch streaming content. “Neomobile” remains a contested term standing in for an idealized distribution subject of platform governance or quasi-agential data generator in/of on-demand delivery cultures propelled by “unlimited” data plans of telecom companies. (See Figure 1)

The plan for many production houses in 2015 was to find and develop the next Narcos or Game of Thrones for the Indian market as a way to compete with Netflix when it finally arrived in India. Soon after, the digital television landscape changed markedly with the entry of Hotstar (later Disney-Hotstar), followed by Netflix and other Desi/Indian streamers like SonyLIV, ZEE5, and ALTBalaji. From just one streamer in early 2015, there were about fifty streaming platforms catering to domestic and international (including diasporic Indian) audiences by early 2022.[2] The video-watching experience of new to mobile phones users as an individualized (and “private”) one, outside of office and home, in commuter trains or on auto-rickshaws, is a scenario I heard from several streaming distributors. For the new streamers, the quality of streaming had to be good enough so that the in-transit mobile phone user stopped watching already “pirated” downloaded content and felt confident enough to stream without encountering buffering. How are streamers reaching neomobiles? How are TV distributors accustomed to broadcasting for so long, shifting their media practices to make “seamless” streaming experience possible for their audiences? How do content curators ensure audiences are able to easily find their desired content on mobile internet? Here, I briefly discuss three distribution practices: telecom bundling, arranging catalogs, and deep-edge computing (with the emerging role of local CDNs)

By August 2022, streaming platforms like ALTBalaji and SonyLIV had already worked out deals with telecom companies such as Reliance Jio and Airtel to have their services be part of bundled offers. Airtel and Jio had emerged as over-the-top (OTT) aggregators, meaning they offer media directly via the internet, bypassing traditional cable services and aggregating streaming apps together. The Airtel Xstream feature aggregated various video apps with a single log-in, subscription, and search. Variously valued packs of streaming-service apps were available through both Jio and Airtel (See Figure 1). One could subscribe to all the different streamers—Disney+Hotstar, Netflix, ALTBalaji, and SonyLIV—or sometimes just one or two in a less expensive pack. SonyLIV’s yearly subscription rate of Rs 1,000 was not affordable for everybody, and as part of telecom bundling through Airtel, Jio, and Vodafone Idea, another significant group of people could watch SonyLIV. While this discounted mobile pack brought in less revenue per consumer than the more expensive direct-to-consumer pack, a SonyLiv official mentioned the benefits. The mobile-pack model reduced acquisition costs and helped increase SonyLIV’s footprint. Furthermore, he reasoned that today’s students—who have less income right now—are consuming SonyLIV on a subsidized mobile pack but after five or six years will become professionals with higher disposable income. If, at that point, they continue liking SonyLIV’s content and streaming experience, they will go for a direct-to-consumer pack to be watched on large TV screens.

In 2015, a former executive of Viacom18 noted that the company was planning to combine the Nickelodeon, Colors, and MTV channels and present their aggregate content on a streaming platform called Voot to be run on an AVoD model. This brought in new design challenges and audience considerations. The Voot interface had to look different from the Hotstar interface as a way to project its uniqueness. Voot’s interface had to address users who were a diverse constituency given the different channels Viacom18 had: Nickelodeon was for children, MTV for the youth, Colors for family. These different users had to find a way to their content. As they were navigating through the Voot interface, users would not be seeing their particular TV channels but rows of catalogs of content. Could a row be assigned to content catalog titles from each specific channel? If MTV, Nickelodeon, and Colors were each going to have their own separate row, which channel would get the top row? Which set of users could be relied on to scroll down a couple of rows to find their favorite channel’s content? In making these adjustments, the publishing team was shifting from the rhythm of live television to the updates of the on-demand online world. The plan was to refresh the content page three times during the day so that the hypothetical user visiting the interface in the morning, afternoon, and evening would see some new content each time.

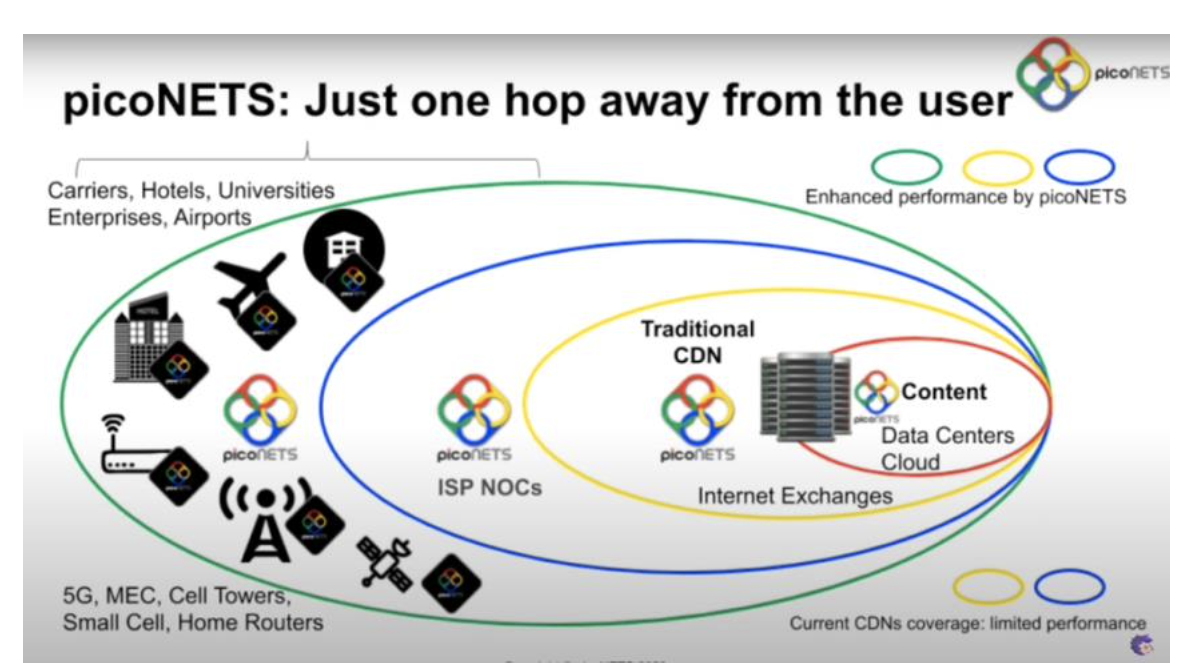

The streaming content that reaches the smart TV and smartphone is often not being broadcast through a multicast signal and intercepted by a satellite dish antenna; rather, these are unique copies being pulled from data center networks by each request from digital devices. Given the scale and flexibility of operations required to cater to a geographically distributed population of customers, the CDN industry is dominated by a few big players like Akamai, Amazon’s CloudFront, and Microsoft Azure.[3] In India, a global CDN like Akamai—given the rack size of its assemblage of servers and its expectations of certain minimum traffic speed and concentration (which some claim to be about 6-8 GBPS)—may not connect with a small internet service provider (ISP) in a tier-2 city in India. Even as Akamai or Netflix are committed to distributing content to localized servers, they could create exclusions based on certain bandwidth criteria that ISPs or their preferred middle-class audiences must meet. Concerns about smaller ISPs not being able to negotiate with big CDN companies on equal terms, and about customers of particular VoD streamers receiving preferential treatment because of better CDN services, have been raised in Indian newspapers. These concerns are similar to net neutrality debates that have unfolded in several countries.[4] Local CDNs distributing this streaming content today are collaborating with local cable wallas (cable operators) who often still remain the last mile operators (LMOs) as they once were in the heydays of satellite cable television. Now, they enact the role of internet service providers as LMOs. Local CDNs further reduce the travel distance for media data packets between the source and destination, shifting the source of data (from “cloud”/data center) to a server closer to the user. picoNets, a local CDN has its cache servers (“deep-edge servers”) located very close to users (See Figure 3). This is a movement from cloud computing to deep-edge computing. As the streaming industry tries to reach out to semi-urban and rural areas of India, the role of local CDNs could become significant in the future. While all CDNs practice some form of edge delivery, the edge for a global CDN might mean a metropolitan city of India and a smaller ISP most likely will have a much local and granular perspective about edge. Local CDN players suggested that the “edge” is not just about local data storage but also could possibly account for different languages spoken in different regions and the range of phones used by “neomobiles” with varied features and affordances.

The at-stake questions in distribution studies are also about the political economy of infrastructures. Domestic video streamers like ALTBalaji and SonyLIV are dependent on distribution infrastructures owned and operated by cloud computing companies, which is not the case with global players like Netflix and Amazon that have their own content-delivery networks such as Netflix Open Connect and Amazon CloudFront.[5] While some domestic streamers consider it a liability, others believe that it frees them to do what they do best, that is, make content. More importantly, control over distribution infrastructure is also about control over what kind of audience data is gathered and who gets to collect and use it, but that discussion will have to wait for another essay.

Image Credits:

- Figure 1: An advert of unlimited telecom data by Airtel (Author’s personal collection)

- Figure 2: Airtel Xtream

- Figure 3: PicoNETS (Author’s personal collection | Courtesy: Prakash Advani, Piconets)

- Scholarship in this burgeoning subfield by Ishita Tiwary, Juan Llamas Rodriguez, Asli Ildir, and Jennifer Kang, all contributors to Amanda Lotz and Ramon Lobato’s edited collection Streaming Video: Storytelling across Borders, has been path breaking. [↩]

- Kumar, Shanti and Aswin Punathambekar. 2022. “Hotstar: Reimagining Television Audiences in Digital India” In Derek Johnson (edited) From Networks to Netflix: A Guide to Changing Channels, Routledge: London and NYC. [↩]

- Chalaby, Jean K. and Plunkett, Steve. 2021. “Standing on the shoulders of tech giants: Media Delivery, streaming television and the rise of global suppliers,” New Media & Society, 23(11): 3206-3228. [↩]

- Lobato, Ramon. 2019. Netflix Nations: The Geography of Digital Distribution, NYC: NYU Press. [↩]

- That said, for its computing needs, Netflix does use Amazon Web Services (AWS) and therefore does have structural dependency. However, Netflix Open Connect Appliances do help Netflix to maintain significant control on the distribution supply-chain. [↩]