Niche Market, Global Scale: Simulcasting Anime Online

Amanda Landa /Flow Staff

With the simulcast of the Lost series finale, and the recent flow post on FlashForward by Tama Leaver, there’s been growing attention around distribution of U.S. television, the appeal and drawbacks of BitTorrent, and digital rights management issues. On the forefront of television flow in regards to internet availability of nationally-bound shows are also questions of restrictions, such as geo-blocking and “legitimate” access to media. Some major U.S. broadcast corporation productions are inevitably caught up in DRM debates, whether affiliated with Itunes or Hulu or some other third party distributor. It is in this media environment that I find certain methods of anime distribution particularly interesting. Seemingly as a method of increasing accessibility and decreasing illegal downloading and turnaround adaptation time, several Japanese anime studios have entered into simulcast distribution contracts with internationally accessed websites, U.S. affiliates, and the Japanese television network that broadcasts to East and South Asian countries, Animax Asia.

[youtube]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kq7O6eR12oM&feature=related[/youtube]

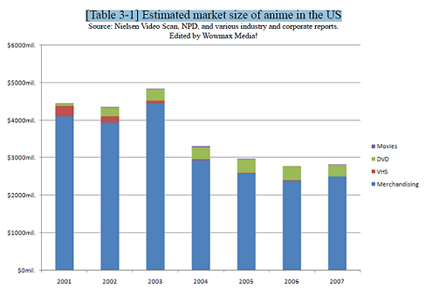

Starting in the mid-’90s the growth of anime and manga fandom in the U.S. was seemingly exponential, and the fansubbing community was largely focused on acquiring and subtitling VHS cassettes, and as Henry Jenkins outlines in his December 2006 piece from Reason magazine, these fan practices aided in the rapid growth and consumption of anime in the early 2000’s.1 However, at the time that Jenkins was writing, U.S. distributors began taking a major hit as the format for trading fansubs was converting to digital file sharing. Procuring their figures from Icv2.com and government studies in Japan, the Japanese External Trade Organization (JETRO), “a government-related organization that works to promote mutual trade and investment between Japan and the rest of the world,”2 cites illegal file sharing as cause for major concern: “According to ICv2, sales of anime DVDs in North America (the U.S. and Canada) fell to $375 million in 2006 from $450 million the previous year. Currently, due to a time lag between Japan and U.S. releases of anime titles, many avid American fans are forgoing the wait for official releases and instead downloading pirated versions.”3

The primary barrier to anime consumption for non-Japanese fans is availability. The anime community often cites their willingness to support U.S. licensing, but the time lag can be frustrating and the relative ease of file-sharing enables many to “preview” certain titles that may not be released for years, or maybe even never licensed by a U.S. distributor at all. The turnaround varies according to the length of the original production, (i.e. subbing/dubbing a film is a much shorter process versus a television series that is currently ongoing) but nevertheless can be a painfully long process for any fan, who through minimal internet effort, can search fansub communities and BitTorrent for more instant gratification. Overall, the licensing process is shortening, but still, for U.S. distributors, the amount of business being lost to illegal downloading is becoming foreboding. Exactly a year after Jenkins’ article, Arthur Smith, President of GDH International–parent company of Gonzo anime studio–wrote “An Open Letter to the American Anime Community” in order to address the decline in DVD anime sales and the process of bringing Japanese content to the U.S. He explains the more time-consuming issues, such as appointing distributors, (a step that requires several negotiation sessions), marketing, translation, and selling to retailers. In his letter he assures anime fans that he is sympathetic to the long waiting process and both he and JETRO state that many anime studios and media companies are “working to come up with solutions that will allow American fans to access high quality legal versions shortly after their Japan [sic] releases.”4

One solution is the revamped website Crunchyroll.com, which specializes in East Asian media. Crunchyroll was previously a download-to-own, user-uploaded content only site, predominantly offering Japanese anime and East Asian television dramas.5 While many fans took advantage of this service, there were still some concerns over the ethical considerations of Crunchyroll accepting donations and charging a premium subscription fee for higher quality downloads. See an interview here with Anime News Network. Crunchyroll announced that they would no longer accept user content after March 31st, 2010 and as of May 1st focused entirely on their digital distribution partnership with Japanese anime industry leaders TV TOKYO, Shueisha, and Pierrot.6 Crunchyroll offers new titles available up to an hour after original broadcast for subscription holders, and one week later for ad-based video viewers. As an additional benefit, Crunchyroll’s site allows access to several countries. The super-popular shonen title, Bleach, is “available in the United States, Canada, Mexico, the Caribbean, Central and South America, the United Kingdom, Ireland, the Netherlands, Sweden, Denmark, Norway, Finland, Iceland, Australia, New Zealand, and South Africa.”7 Of course, these episode are released with English subtitles, which represents a certain linguistic hegemony that can’t be adequately addressed here.

Some major U.S. anime distributors, such as Funimation and Viz Media have begun supplying both subtitled and dubbed anime titles on Hulu.com. Funimation has even acquired the rights to simulcast new titles, which began in late April of this year, by entering a simulcast partnership with Fuji TV’s Noitamina block.8 Also, the kinds of titles being offered by both Viz and Funimation seem geared to appeal to the fairly seasoned anime fan: from InuYasha, The Final Act (Viz Media), a Cartoon Network regular, to the period drama House of Five Leaves (Funimation). Some of the more popular back-catalogue shows are also available in both subtitled and dubbed version for each side of the great debate divide. Funimation’s new simulcast titles are available on Hulu, Funimation.com, and the Funimation Channel on Youtube.com and require no subscription fee in order to access the simulcast benefits. The primary drawback to making new titles available on Hulu.com, of course, is the geo-blocking of Hulu’s content to any country other than the U.S. These U.S. and European centered distribution options also work in conjunction with the already established transnational East and South Asian anime network, Animax Asia, a Japanese TV network owned by Sony Pictures Entertainment, which spearheaded the simulcast movement making new shows available in Hong Kong, India, Philippines, Taiwan, as well as India, Bangladesh and Pakistan.9

What I find interesting about these observations is their significance in illustrating a changing media landscape. In World Television from Global to Local, Joseph D. Straubhaar tracks international television flow in regards to cultural proximity, access and production, and after the feature film, cites animation as “the other most centrally produced global genre.”10 Also, Koichi Iwabuchi asserts that while Japanese animation can be characterized as an “odorless commodity,” a product devoid of the cultural, racial, and bodily imprints of the producing nation, he also argues that anime has “become recognized as very ‘Japanese’ in a positive and affirmative sense…Euphoria concerning the global dissemination of animation and computer games prompted Japanese commentators to confer a specific fragrance on these cultural products”11 Due to the quick turnaround of the simulcasting, the episodes are only available with the original Japanese voice actors subtitled in English, which I posit factors into the overall cultural capital and thereby the very “fragrance” that appeals to Non-Japanese anime fans. These recent developments interest me because it illustrates how a single national pop cultural movement from a television specific medium must evolve to accommodate a global fandom that is moving faster than the speed of money to an internet-driven international platform.

1. House of Five Leaves

2. Anime Dreams Coming True: Gonzo and Funimation, Distribution Partners

3. Anime Market Chart

4. Gonzo and Funimation, Distribution Rights

5. Anime Channel banner on Hulu

Please feel free to comment.

- http://reason.com/archives/2006/11/17/when-piracy-becomes-promotion/ [↩]

- http://www.jetro.org/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=663 [↩]

- http://www.jetro.org/trends/entertainment_news_1.php [↩]

- http://www.jetro.org/trends/entertainment_news_1.php [↩]

- http://www.animenewsnetwork.com/news/2010-03-10/crunchyroll-ends-its-download-to-own-service [↩]

- http://www.animenewsnetwork.com/news/2010-03-10/crunchyroll-ends-its-download-to-own-service [↩]

- http://www.animenewsnetwork.com/news/2010-06-02/crunchyroll-to-simulcast-bleach-tv-anime [↩]

- http://www.animenewsnetwork.com/press-release/2010-04-15/funimation-enters-simulcast-agreement-with-fuji-tv [↩]

- http://www.animenewsnetwork.com/encyclopedia/company.php?id=2004 [↩]

- Straubhaar, Joseph D. World Television: From Global to Local. Los Angeles: Sage Publications, 2007. 170. [↩]

- Iwabuchi, Koichi. Recentering Globalization: Popular Culture and Japanese Transnationalism. Durham: Duke University Press, 2002. 30-31. [↩]

Great column, Amanda!

Hi Amanda, very interesting article. I think you’re totally right — this example speaks to many ongoing issues related to global media, new media, cultural commodities, etc. It will be interesting to see what ends up happening re: distribution and the impact that may have on other global media products.

If you’re an anime fan you’re going to love AnimeTycoon. This site has a huge catalog of shows that are dubbed or subtitled.