The Revolution is Televised

Julia Lesage / University of Oregon

While watching a thrilling documentary on Independent Lens recently, Burma VJ: Reporting from a Closed Country, I was reminded of all the now deteriorating VHS footage on shelves that documented the grassroots changes that took place during the Sandinista revolution in Nicaragua from 1979 to 1990. And the question arises, should there be an archive of this material and what would the consequences be? That is, I can imagine the usefulness of such an archive, which could digitize tapes that were shot both by foreigners sympathetic to the Nicaraguan revolution and by Nicaraguan videomakers, such as the Video Alternativo collective with Sandinista rural and industrial trade unions. This video archive of Sandinista Nicaragua could collect both raw footage and finished work, and perhaps build up a file of translated interviews. It would shape history.

One of the reasons for wanting an archive is to create a people’s history around this utopian political moment, which touched the lives of so many Nicaraguans, especially those whose accounts of the revolution will not enter official histories in the future. I was privileged to understand and participate in that process through teaching grassroots video production in Nicaragua with the CST (Central Sandinista de trabajadores) labor union. However, as time has passed, both the video that the group, Video Alternativo, shot over the years and that which I and Chuck Kleinhans shot during our visits has deteriorated in storage (for the Nicaraguan videomakers, it is worse since any media stored in a tropical country decays much faster because of the heat, moisture, and mold).

The Sandinista government was very receptive to us, tourists of the revolution, because they saw us as the key to building a solidarity movement back in our home country. This was a time when solidarity meetings in the United States were organized around a screening and discussion. My own introduction to the Sandinista revolution came at just such a meeting, led by an organizer who went around Chicago with what we called “the Nicaragua film” (I no longer remember the film’s title).

Many professional and independent filmmakers went to Nicaragua, organizing shoots and working on a tight schedule with the goal of producing a timely film. I was one of a more ragtag group of mediamakers, capturing the revolution in VHS. Knowing the potential use for our video work, many of us who went on solidarity trips went with bulky VHS cameras, extra batteries, and whatever electronic supplies we thought we might need; I wore a backpack containing a small Canon VHS deck and my partner Chuck Kleinhans shot with a camera tethered to that deck. So many privileged travelers from the United States and Europe shot similar footage with farmers, small factory workers, women, school children, market vendors, and militias organized to fight the contras. Now the videomakers are aging and all this documentation potentially lost.

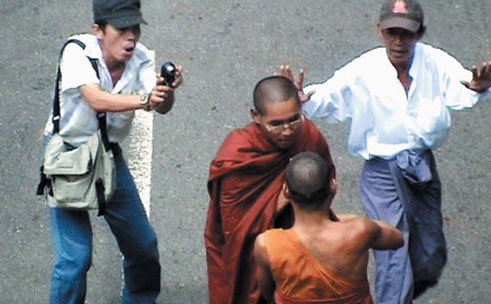

In the beginning, I referred to the documentary Burma VJ. That documentary contains within it many scenes that show how the police state as well as the revolutionary grassroots journalists from within Burma use camcorder and cell phone video. The VJs provided footage of rebellion, mass resistance, and military retaliation to the outside world, so that their reportage has been broadcast on television news throughout the world. The state apparatus identified each VJ via police recordings, hunted them down, and broke up the network of grassroots video reporters.

What is not questioned in the Burma VJ film but something I would question in relation to the archive I propose, even twenty years after the Sandinista revolution, is the issue of how grassroots mediamakers’ identifying faces, people, leftists, and demonstrators can also serve the forces of repression. In the ebullient moments of street protests, with crowds growing more numerous everyday, the Burma VJs’ cameras capture the faces of hundreds of ordinary people. The demonstrations are quashed, but the footage in the documentary can still be used to identify the faces in the crowds.

In this way, two contradictory factors enter into my desire for an archive of video documenting “Nicaragua Libre,” as Sandinista Nicaragua was known. I know the window for preserving the video taken in those years is very short, due both to what gets thrown out and videotape’s rate of decay. But I also feel an obligation to protect those in the videos, both those in the foreground, who may be giving interviews, and those in the background, perhaps attending a union meeting or gathering on the street. As independent videomakers, we take a lot of time to complete our documentaries; but the state apparatus that now also “data mines” images has lots more technology and personnel at its disposal to scan and use these images quickly and effectively for surveillance and identification.

In retrospect, we know that the Stasi in East Germany collected huge dossiers of photos and reports on individuals, and it has taken years for the extent of this paper empire to come to public awareness (fictionalized in The Lives of Others, 2006). More recently, mobile phones were widely used in protests during Iran’s disputed elections and consequently monitoring technology led to activists’ persecution and arrests. Cell phone messages, photos and video, Flickr, YouTube, Skype—all these are powerful tools for activism, but they have other consequences as well.

I do not have a way around these contradictions. But they keep me from romanticizing the archive, much as I seen the need to preserve these documents from a revolution. We need these videos for an in-depth understanding of a moment when we could see a people’s optimism and social change.

Image Credits:

1. Burma VJ: Buddhist monks in anti-government protest

2. Filming Burma VJ

3. Photo by Susan Meiselas from her book Nicaragua

Please feel free to comment.