Chicago 1968 and the Kaleidoscopic Mosaic of the 1960s TV News Experience

Michael Socolow / University of Maine

“Chicago in 1968 was probably the turning point,” concluded Bill Small, the veteran CBS and NBC News executive, in 1970. “The television coverage of the streets of Chicago during the 1968 Democratic Convention brought the audience resentment boiling forth. Television,” Small explained, “has become fair game for the man on the street and the man who became Vice President.”[1]

What Small called “fair game” might be more precisely categorized as a “legitimate object of criticism.” By the 1970s, television in general, and television news specifically, had become a major topic in public discourse. This national discussion was enlivened by the growing politicization of TV criticism throughout the 1960s. In 1964, Senator Goldwater chided the “Eastern elite press” in his campaign for the presidency, offering an early model for attacking the media. Then, as the Vietnam War intensified, the Johnson administration – and President Johnson himself – seethed with anger at network TV news operations. TV news, he once complained, seemed to be virtually “controlled by the Vietcong.”[2]

By the time President Nixon sent Vice President Spiro Agnew out to criticize the media in 1969, the proposition that the nation’s most popular vehicles of information were controlled by unknown and distant elites had become relatively widespread. Agnew’s attacks clearly struck a chord, as his channeling of a largely disbursed but widespread feeling earned him national celebrity.

By 1970, everyone, it seemed, had an opinion about television news and its portrayal of reality. Now two new books help us understand how Americans arrived at that point by returning to the Democratic National Convention of 1968, and more specifically, the television coverage of that event experienced by millions of Americans. They spotlight the pivotal moment that sparked widespread debate about television’s ability to provide accurate reporting. Chicago 1968 was more than a single historic occurrence; it seemingly crystallized and amplified the looming uneasiness with TV that had been brewing in American culture and society since the beginning of the decade.

MIT professor Heather Hendershot’s When the News Broke: Chicago 1968 and the Polarizing of America (University of Chicago Press, 2023) offers the most precise, comprehensive, critical and detailed reading of the televisual experience of Chicago 1968 yet published. When the News Broke compares the actual images broadcast to American homes with archival research and interviews revealing the myriad behind-the-scenes production challenges erupting throughout the event. This close detailing of the difficulties inherent in live TV news broadcast production comprises one of the book’s most significant contributions.

Crossed Wires: The Conflicted History of U.S. Telecommunications from the Post Office to the Internet (Oxford University Press, 2023), the new book by University of Illinois Professor Emeritus Dan Schiller, opens in Chicago in 1968, just as the Democratic National Convention is about to begin. Schiller selects that moment because the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers (IBEW) had begun a strike against the Illinois Bell Telephone Company just weeks earlier, at a time when installing telephone and microwave relay links essential for establishing comprehensive live TV coverage was necessary. The strike eventually caused havoc with TV coverage, as the negotiated compromise (Schiller terms it “an extraordinary fix”[3]) brokered by Chicago Mayor Daley’s office failed to insure the networks could deliver live TV reports from downtown Chicago and the Convention floor simultaneously. Instead, the strike forced network producers to time-shift previously recorded films and videos (motorcycled from the police riot in downtown Chicago) and jam those recorded images into on-going live coverage.

Distortion and confusion ensued. The chaos intensified an erupting political crisis while exacerbating the messiness of the television production. Chet Huntley, David Brinkley, Walter Cronkite, and others scrambled to assemble coherence, but they lacked adequate information. Disparate events occurring both live and via recorded materials made the relayed images on America’s TV screens seem jammed together, chaotic, and almost kaleidoscopic. No amount of calm explication, or reasoned address, could properly frame the experience of viewing so much actual violence, rioting, and disorder. Nor was the disruption limited to the streets of Chicago; from within the convention hall itself, where CBS reporter Dan Rather was belted by security guards and shouting matches erupted everywhere, the transmitted images proved shocking and memorable. The precisely planned news production devolved into a mosaic of confusing and clashing images, some of it explainable but much of it perplexing and angering to viewers at home.

America’s TV audience wasn’t accustomed to this experience. Television, in the mid-1960s, was carefully planned, produced and programmed. Even programs loaded with inherent suspense, such as newscasts describing the Vietnam War, or live sporting events, were meticulously prepared and structured. The world in which breaking news from anywhere on the globe could be transmitted live with powerful immediacy had yet to arrive. Only brief flashes of that media future – such as when Jack Ruby shot Lee Harvey Oswald on November 24, 1964, a shocking event that only NBC carried live – occurred before 1968. A series of technological innovations were required for the future we now take for granted to emerge. These included the establishment of reliable satellite relay, the use of color TV equipment and associated technologies, the widespread employment of videotape, and the development of new electronic news gathering technologies and techniques. These innovations percolated throughout the mid-1960s, but their consistent deployment only occurred beginning in 1968. When reviewing U.S. media history, a remarkable transformation in TV news between 1967 and 1969 becomes clearly visible in hindsight. The television being watched from Chicago in 1968 differed in significant ways from the television Americans watched just a year or two earlier.

Making sense of this rapid and disorienting media revolution proved difficult at the time. Numerous scholars and theorists, ranging from Daniel Boorstin to Marshall McLuhan to Guy Debord, attempted to explain this world transformed by electronic presence and immediacy.[4] Their works differed in notable ways, but one clear thread uniting their inquiry was the pressing need to describe a transition from older conceptions of reality to a contemporary world filled with newer experiences of mediated reality. This required addressing epistemology and authenticity while pursuing something akin to natural philosophy. Much writing about television emerging in this period was peppered with unsupported assertions about TV effects, often generated from simple TV-watching experience. Nobody – not the scholars, not the newspaper and magazine critics, nor the viewers at home – fundamentally understood, with clarity and precision, their shared experience. Yet it was precisely because the TV revolution of the 1960s was so experiential and intimate, simultaneously personal and public, that everyone developed an opinion about the vexed and confusing relationship between TV and reality.

Many viewers watching the 1968 Democratic Convention sought to share their opinions. When the News Broke offers a fascinating reading of letters sent to the TV networks and the government in response to the Chicago convention coverage. As established by quantitative and qualitative analysis, viewers at home primarily saw what they wanted to see. The bloody “police riot” in Chicago was experienced, in many tranquil homes across the continent, as hippies and radicals being punished appropriately for fomenting civil unrest. Events captured on film and video, and information voiced by credible news reporters, was, for many Americans, simply unpersuasive. It even seemed “fake” to some. Many viewers apparently added the Chicago TV experience to the accumulating mosaic of disturbing imagery that had been flowing into their homes from such distant locales as Saigon, Prague and Watts over the previous several years.

In retrospect, that’s what made the television experience of Chicago 1968 so revolutionary. As both Schiller and Hendershot concur, Chicago comprised a critical juncture in the history of U.S. media. Yet hindsight shows its legacy extends far beyond media history. In widely disseminating a confusing and kaleidoscopic experience, filled with disorienting and disconnected moments, it forced viewers to approach TV news as, essentially, a national Rorschach test. What viewers thought they saw became their self-curated reality, regardless of what any news film showed or what any anchors or politicians proclaimed. Towards the end of Hendershot’s book, she suggests the audience may have been unconsciously primed to mediate the Chicago convention by reference to the cascading events preceding it in 1968. Shocking assassinations, the Tet Offensive, Soviet tanks rolling into Czechoslovakia, the takeover of universities, and protests and riots in Paris, all may have oriented the American TV viewer to a new world where news could be delivered instantaneously, live and in-color, with much detail but little context. Everyone watched TV together, but they were trying to piece together reality on their own.

Thus everyone became a television expert. Watching TV news evolved into an exercise in deciphering reality while sifting and rejecting confusing or unwelcome information. Chicago 1968 intensified the splintering of a widely shared and collective understanding, and this historic media experience eventually proved ripe for exploitation by shrewd politicians. Whether powerful people on TV were lying to you or not suddenly became a very important question by 1970 – and it didn’t matter whether the lies seemed to come from the President of the United States or “the most trusted man in America” who delivered a nightly newscast on CBS.

In this sense, television never recovered from Chicago. And neither did we.

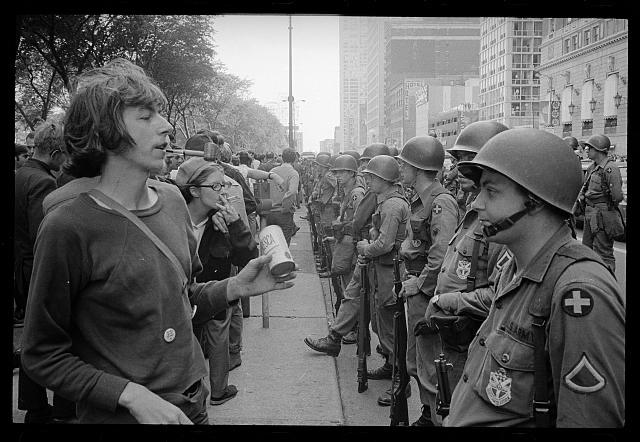

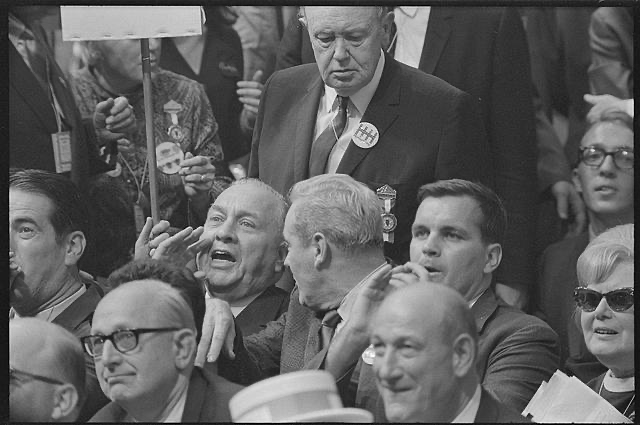

Image Credits:

- Young “hippie” standing in front of a row of National Guard soldiers, across the street from the Hilton Hotel at Grant Park, at the Democratic National Convention in Chicago, August 26, 1968.

- Heather Hendershot’s When the News Broke: Chicago 1968 and the Polarizing of America (University of Chicago Press, 2023.

- Dan Schiller’s Crossed Wires: The Conflicted History of U.S. Telecommunications from the Post Office to the Internet (Oxford University Press, 2023).

- Illinois delegates at the Democratic National Convention of 1968, react to Senator Ribicoff’s nominating speech in which he criticized the tactics of the Chicago police against anti-Vietnam war protesters.

- William J. Small, To Kill a Messenger; Television News and the Real World (New York: Hastings House, 1970), xi. [↩]

- Chester Pach, “Lyndon Johnson’s Living Room War,” New York Times, May 30, 2017, https://www.nytimes.com/2017/05/30/opinion/lyndon-johnson-vietnam-war.html. [↩]

- Dan Schiller, Crossed Wires : The Conflicted History of U.S. Telecommunications from the Post Office to the Internet (New York: Oxford University Press, 2023), 1. [↩]

- Daniel J. Boorstin, The Image (New York: Atheneum, 1962); Guy Debord, Society of the Spectacle (Detroit: Black & Red Press, 1970, c.1967); Marshall McLuhan, Understanding Media (New York, McGraw-Hill, 1964). [↩]

Nice piece, Mike. I lived through it and remember it. One of my most vivid TV memories while in college was all the guys gathering to watch Uncle Walter every night. We knew we would likely end up in that war but we watched anyway.