Profiles without Agency? BeReal and the Future of Profile-Building

Gabriel Wisnewski-Parks / WEstern Carolina University

The Saturday Night Live BeReal sketch, set in a tense bank heist scene, seems to tell us we should feel anxious about the app (Figure 1). But what exactly should we be anxious about when it comes to BeReal? My claim is that we need to pay attention to what BeReal reveals about attitudes towards authenticity, identity, and agency, particularly as they relate to the vital social process of profile-building. WhatBeReal seems to offer users is social media engagement without public curation of profiles. Analyzing how BeReal’s affordances might impact user attitudes and behaviors towards profiles is important, as we try to anticipate BeReal’s contributions to the trajectory of social media platforms and as we grapple with how identity formation and agency may be shaped for future generations of users.

Research widely demonstrates social media spaces as important forces of identity development, especially for young people. As meaningful locations for socialization and self-expression, many scholars analyze how platforms ranging from Instagram to WeChat enable and constrain user self-perceptions of authenticity along with acquisition of social capital (Hu, Hu, & Hou, 2022; Kreling, Meier, & Reinecke, 2022). Fundamental to social media’s sway on identity formation has been the process of users posting unique content and cultivating public profiles (Dawkins, 2015). Users curate profiles through pictures, avatars, bios, and through choosing what content to post and with what frequency. Over time, identities are expressed and negotiated through collections of content featured in feeds, walls, or pages.

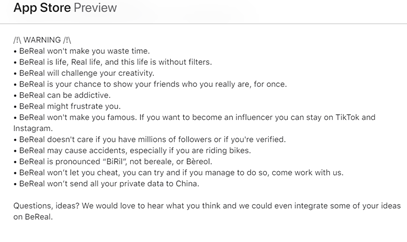

But BeReal treats profiles differently. The minimalist design of the app fosters nostalgia for bygone days of earlier and simpler social media. Yet an assumption in BeReal’s branding seems to be that profiles themselves may be inimical to ‘authentic’ social media engagement. Consider the Apple Store preview of the app, featuring a ‘warning’ message for prospective users: “BeReal is your chance to show your friends who you really are, for once”, and “BeReal won’t make you famous. If you want to become an influencer you can stay on TikTok and Instagram” (Figure 2).

BeReal’s narrative holds that user experiences on competing social media platforms lack authenticity. The implication seems to be that the processes of content creation engendered by profile curation are to blame for failed authenticity, as such processes lead to users seeking fame, or pretending to be something they aren’t for peers. And though it ironically took little time for celebrities and influencers to migrate to BeReal (Gale, 2022), the app’s branding nonetheless demonstrates a cultural desire for a space where users can experience authenticity in a way that relies less on the curation of profiles. Clearly, BeReal is positioned within discourses of authenticity. However, I think a more fruitful analysis of the app requires an updated vocabulary of identity.

In their pertinent book, You and Your Profile: Identity After Authenticity, philosophers Hans Moeller and Paul D’Ambrosio (2019) theorize what they call “profilicity” (profile-based identity) and how it has proliferated in contemporary societies. With identity understood as performed, profilicity diverges from two prevailing historical models of identity: sincerity and authenticity. Sincerity represents identity as achieved through internal commitment and external adherence to one’s social roles and their norms. Conversely, authenticity marks an internal rejection of social roles; it demands social masks be shed, in favor of a perceived true, inner self-core. But authenticity is paradoxical: one’s personal sense of a true, unique self must always be communicated, performed to some audience for validation. Authenticity remains the paradigm, the vocabulary for discussing identity on social media. But it is misleading to speak of authenticity as a real possibility on any platform, especially BeReal.

However, in profilicity, profiles are not inherently ‘fake’ precisely because users can still choose to commit to them. Much like museums curate art for display, social media users display profiles, and can emotionally invest in them as performances. Moeller and D’Ambrosio (2019) refer to this phenomenon with the paradoxical notion of “genuine pretending”.Under conditions of profilicity, Instagram profiles (for example) are purposefully staged and ‘curated’, but public commitment to and care for profiles can still meaningfully build identity. This theoretical understanding helps us reframe how we understand BeReal’s potential effects on user agency.

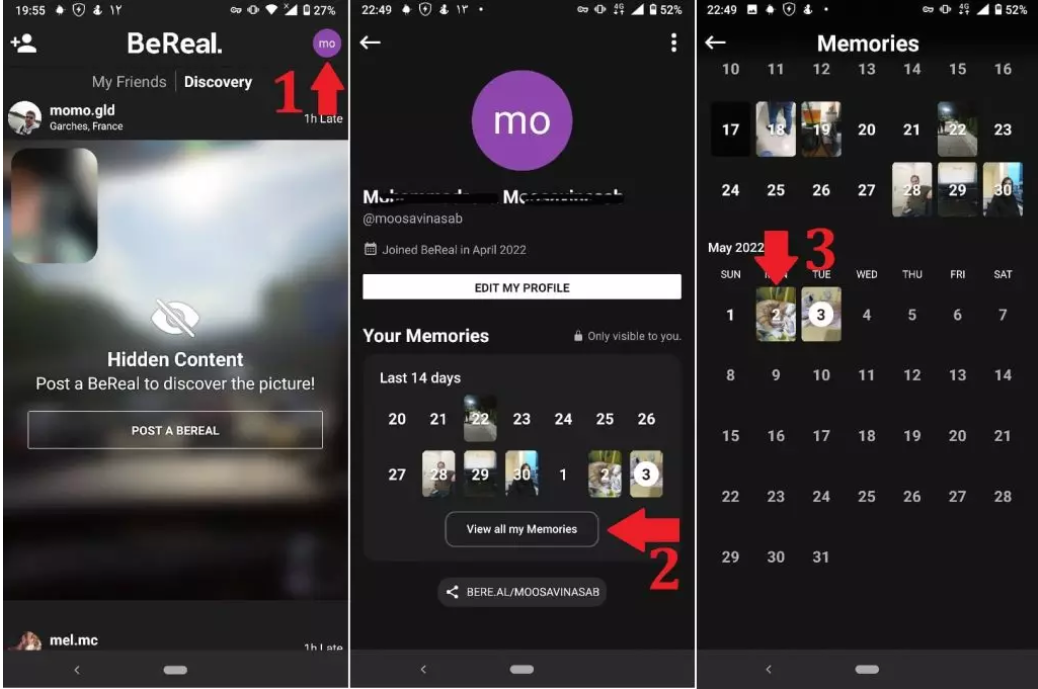

The ways platforms promote profile-building processes are integral to how users understand themselves. But BeReal’s affordances present changes to this process. Where it does have tried and true social media features like the endless scroll, BeReal features no ‘wall’, feed, or page consisting of a chronology of user posts available for followers or the public to view. Instead, BeReal features a ‘memories’ page, which is private to users (Figure 3). Rather than engaging users to curate a collection of posts over time, BeReal optimizes engagement via adherence to its daily posting rules. The inducement for users is to ‘spontaneously’ produce daily content, as opposed to the relative freedom to curate content found on other platforms. BeReal users cannot go to a friend’s profile to view their content. These features seemingly undercut the value of profiles, in the name of alleged authenticity. And true, Instagram (for example) does enable users to apply filters to posts, to perform curated versions of themselves. But under conditions of profilicity, users can still feel emotionally invested in the performances. With its orientation to the act of daily posting, BeReal creates an experience where users can participate on social media without having to invest in profiles.

If BeReal is the social media for people who hate social media, then what exactly is it that people hate? One answer may lie with anxieties around choice and risk. Profiles necessitate curation, they demand users make choices that carry risks to their reputations and self-concepts. Cultural critic Slavoj Žižek has theorized about the commodification of cultural desires for the essence of social experiences without their respective risks. Illustrating with the example of dating apps, Žižek points to ways that affordances of modern social dating systems cultivate desires for “love without the fall” (Marshall, 2015). Meaning, users perceive the possibility for genuine, authentic romantic encounter, without the risks that relationships necessarily carry. We can observe this in other realms, with examples of non-alcoholic beer, or coke without sugar, etc. The point is we often want the core of social experiences without their risks, and social media platforms shape and produce these desires quite well.

Similarly, what BeReal may represent is a cultural desire for the essence—connection—of social media without the risks of profile curation. Due to the posting rules and app interface, BeReal might provide a psychological experience of social media engagement without the perceived risks that come from committing to profiles. These affordances of the platform, despite seeming to constrain user agency, remain attractive to many users. As academic and YouTube creator Julian de Medeiros explains in a Lacanian lecture on the ideology of BeReal, he enjoys the app (and suspects many others do) “because it is deeply inauthentic. Because it is the ultimate form of surplus enjoyment…surplus enjoyment is the enjoyment of discipline…so when an app tells me what to do at a certain given moment in time, this is enjoyable to me…I don’t have to be the active-arbiter-agent of choosing when to post or how to post” (Julian de Medeiros, 2022). Medeiros and other commentators such as R.E. Hawley in The New Yorker (2022) have argued that BeReal’s narrative belies the fact that the experience it offers users is still a performance. This seems correct. A difference, however, between BeReal and many peer platforms is that it arguably takes away elements of choice: not just choices in day to day posting, but also within the process of profile investment and performance.

Whether BeReal’s seeming move away from the centrality of profiles on social media signals any less of an anxiety-inducing user experience remains to be seen. Regardless of BeReal’s longevity, scholars should attend to its affordances for what they may promote for identity work. Social media platforms increasingly shape user self-perceptions of authenticity, and together with curation behaviors these processes significantly contribute to overall psychological and emotional wellbeing (Hanckel, Vivienne, Byron, Robards, & Churchill, 2019). Moreover, as scholars such as Moeller and D’Ambrosio demonstrate, profiles are likely to become ever more important features of identity and for wider social systems. As BeReal’s influence unfolds, we should certainly be concerned with issues such as the blatant levels of surveillance it implements and incentivizes. But our attention should also be directed towards the more subtle platform affordances, like how the content BeReal users create over time is made private and not displayed for others. These affordances may shift cultural attitudes and expectations towards profiles and user senses of agency. Ultimately, BeReal provides us with an intriguing opportunity to interrogate how much agency we want in the curation of our profiles—and what user agency should mean for the future of social media.

Image Credits:

- Figure 1: Miles Teller on SNL, stalling a bank heist to use BeReal. Author’s screen grab of YouTube video.

- Figure 2: BeReal’s Warning Message on the iOS AppStore. Author’s screen grab.

- Figure 3: Screenshot of BeReal’s private memories calendar. Author’s screen grab.

- Figure 4: Julian de Medeiros’s YouTube lecture on BeReal and the ideology of authenticity. Author’s screen grab of YouTube video.

Marshall, C. (2015). Slavoj Žižek Explains What’s Wrong with Online Dating & What Unconventional Technology Can Actually Improve Your Love Life. Open Culture. Retrieved from https://www.openculture.com/2015/12/slavoj-zizek-explains-whats-wrong-with-online-dating.html

Moeller, H.-G., & D’Ambrosio, P. J. (2019). You and Your Profile: Identity After Authenticity. Columbia University Press.

Hawley, R.E. (2022). BeReal and the Fantasy of an Authentic Online Life. The New Yorker. Retrieved from https://www.newyorker.com/culture/rabbit-holes/bereal-and-the-fantasy-of-an-authentic-online-life