Postfeminism Lost and Found: Tracking the “Runaway Bride”

by: Diane Negra / University of East Anglia

“I believe that under current conditions distinguished by the hyperspeed of media mobilization and a hyperabundance of images and discursive output, hypers(t)imulation and overpresence produce events that verge on a necrotic form of history even before their achievement of narrative closure.”

–Kevin Glynn, Tabloid Culture: Trash Taste, Popular Power and the Transformation of American Television, 19.

“No one cares about missing men.”

–Chris Rock to Conan O’Brien when asked about the Runaway Bride case on Late Night With Conan O’Brien, May 31, 2005

The story of a missing/murdered white woman or girl dominates American television. Although they adhere to different generic codes, forms including cable news, prime time dramas and court television all centralize microdetailed investigations into the manner of and motive for female death. Indeed, the primary narrative energy in all of these forms is crucially linked to the prospect of “discovering” the dead woman again and again.

In this piece I assess a recent seemingly minor mediathon that produced a distinctive celebrity for its focal figure; media events tend to engage ideological flashpoints and this one, I would suggest, is no different. The story of the “Runaway Bride” which consumed U.S. media outlets for a few days at the end of April and beginning of May turned on 32-year-old Jennifer Wilbanks, a Duluth, Georgia bride-to-be who secretly ran away via Greyhound bus a few days before her wedding. In the time that Wilbanks was missing a well-rehearsed and familiar media response swung into operation driven by the assumption that the story of the vanished white middle class woman ends with a corpse. Wilbanks’ family (particularly her father, father-in-law and fiancé) and friends were repeatedly broadcast expressing their fears that she was the victim of foul play.[1] Meanwhile, a large and costly search operation that had volunteers canvassing local rivers and woods was undertaken with nationwide publicity stressing discourses of protective paternalism and hometown solidarity. Yet the story abruptly changed course with the revelation that Wilbanks had run away on her own, traveling first to Las Vegas and then to Albuquerque, in an effort to avoid her upcoming wedding. This unconventional ending to a familiar script was greeted by public anger and scorn for a woman who had flouted the usual rules of the “missing woman” story. News anchors on CNN said things like “I couldn’t believe it when I heard on Saturday morning that she’d turned up alive.” People on the street interviews and newspaper opinion polls lambasted Wilbanks as selfish and cruel; a commentator for Fox News opined that “Wilbanks should be disowned by her parents, shunned by friends, and bitten by the family dog.”[2] Through such forums it became evident that Wilbanks had spoiled the expectations of many more people than just her fiancé and family.

What are we to make of the vehement media response that defined the overnight celebrity of Jennifer Wilbanks? I argue that Wilbanks violated two of the most high-profile narratives of contemporary femininity – the wedding story and the abduction/murder story. Simultaneously rejecting a number of the “approved” roles for women in a postfeminist culture – the bride, the daughter, the hometown girl – she exhibited altogether the wrong sort of desperation. Although recent popular culture has displayed a penchant for constructing femininity as romantically/sexually desperate, Wilbanks was not the neurotic romantic comedy heroine in zealous pursuit of “her man,” nor was she even a “Desperate Housewife.” Rather her spontaneous celebrity generated a challenge to the security of current postfeminist archetypes and interrupted a familiar representational dynamic in which the reasons why a middle class woman could disappear in America are officially mystified but culturally “understood.”[3]

The fervent denunciations of Jennifer Wilbanks rang oddly in the context of the story’s seemingly lighthearted “Runaway Bride” promotional tag. The phrase itself is doubly associative, calling to mind both the classical screwball comedies of the 1930s as well as the 1999 Julia Roberts romance. Scholarship on screwball consistently reads the runaway bride as a liberating, empowered image. Famously, of course in It Happened One Night Ellie Andrews’ flight is away from what is expected of her and toward her desire. By contrast, the Jennifer Wilbanks story is marked by a decisive momentum from but there is no corresponding to and Wilbanks’ haphazard progress was rather a narrative letdown.[4] What happened in this mediathon may thus constitute an instance in which the conventions of screwball comedy are “re-purposed” but without their original egalitarianism. This, I would suggest, is very much in keeping with a postfeminist media culture that tends to recycle classical representational codes but strip them of their progressive and/or ambivalent features.

Another important level of intertextuality connected the evolving news story to Runaway Bride, a film that worked to pathologize the bride with “cold feet” – in that film Roberts’ smalltown girl, Maggie, is shown to repeatedly abandon men at the altar because of her deep-seated identity crisis (again the bride’s trajectory is evasive rather than purposive).[5] In this respect the film and the Jennifer Wilbanks case meshed perfectly and led on to what would become the penultimate phase of the story where Wilbanks was re-cast as troubled person, with an ongoing pattern of criminal/irrational behavior of which her flight from a wedding she was uncertain about was just one more example. While there were strident calls for Wilbanks to make restitution for the money spent in searching for her, once she took up the place of a regretful, troubled woman who was (one imagines uneasily) reconciled with her fiancé, the “Runaway Bride” mediathon was just about over. In its final phase the story transmuted into a public mental and emotional health narrative with articles appearing about how the ever-growing scale and cost of an American middle class wedding might well cause brides to do a runner before the big day – some stories even featured a set of “warning signs” about how to spot a potential runaway bride among family and friends. In a hypermatrimonial, postfeminist culture, crisis converts to diagnosis even as our memory of recent mediathons fades out.

Notes

[1] In doing so, incidentally, they were implicitly asserting their own innocence of any crime – of course when women are murdered, it is male partners and family members who are the most ready suspects given the statistical realities of such crime.

[2] Wendy McElroy, “Runaway Bride Lost in Junk Journalism,” May 11, 2005, FoxNews.Com. Notably, when the “runaway bride” was filmed at an airport traveling home to Georgia the spectacle complied with familiar codes of criminal performativity. Wilbanks was led along by two police officers as she hunched under a blanket.

[3] See Allison McCracken’s “Lost” in Flow 1(4) Nov. 19, 2004.

[4] The fact that she drifted to the outskirts of anonymous Sunbelt cities only further feeds the problem and sharpens the distinction between hometown sociality and urban anonymity at work in accounts of Wilbanks’ flight.

[5] Though observant viewers may note that in many ways the film validates Maggie’s desire to avoid marriage in a town that though superficially idyllic is full of people who are rather viciously unkind about her “Runaway Bride” status. In this sense, it is important that closure is achieved when Maggie seeks out Ike in Manhattan and their wedding happens elsewhere and privately, with Maggie’s neighbors and friends having to rely on phone calls to establish that she has finally been married.

Image Credits:

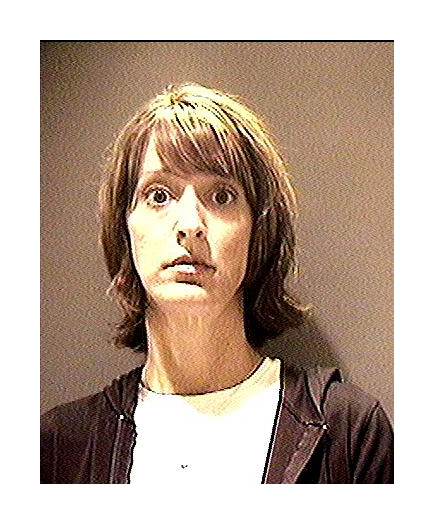

1. Jennifer Wilbanks

Please feel free to comment.

Pingback: FlowTV | This Issue on Flow (08 July 2005)

the semantics of “postfeminism”

I too paid a great deal of attention to the fallout of the “Runaway Bride” incident. Like Negra, I also that it was interesting that people seemed to prefer she turned up dead….

Bringing me to my point about her use of the term “postfeminism” — are we referring to a particular historical moment? Are we assuming that the work of feminism has come to a close (which is what the etymology of “post” would imply)? It would seem that this particular instance would highlight that as a society, we are definitely NOT post feminism — specifically in terms of ideological and practical struggles for women’s equality. And as for the idea that the term “postfeminism” refers to a particular historical moment, is the idea that a woman should be dead rather than running from marriage really THAT different from, oh, say, 1953?

This might seem nitpicky and beside the point, but the steam gathering behind the term is troubling to me for a bunch of reasons and the instance of the “Runaway Bride” seems to offer a particularly salient moment at which feminism isn’t post anything at all….