Marshall’s Children

Charles R. Acland / Concordia University

Who are Marshall’s children?

You may have read that title and assumed the article was going to be about Eminem.

An older generation would have reflexively connected “Marshall” with “Tito.”

Okay, how many are now thinking about the Jackson 5?

McLuhan is the Marshall in question, a name all media scholars know as either essential or essential-to-avoid reading. And we are all Marshall’s children. Though we can trace several lines of ancestry for communication and media studies–for instance, to the mass communication research programs of the Rockefeller Foundation of the 1930s–we must acknowledge the bump in department formation during the expansion-driven university economy of the 1960s, a bump coinciding with the extraordinary luminescence of McLuhan’s popularity. This is not to say that McLuhan sparked this bump (though his foundational influence in my institutional home, the first degree-granting communication studies department in Canada, is indisputable), nor that his writings had a unanimous seal of scholarly approval, which they did not. Even at the height of his fame, some denounced him as a charlatan, establishing a Manichean dynamic that continues to this day. He survives as both patron saint of Wired magazine and as a thinker who tends to be left in the bottom drawer when it comes to media studies course reading lists. His ideas exist in the balance between fashionable–or fashionably retro–and just plain out of touch.

McLuhan’s influence upon the 1960s and subsequent decades has been such that he, in the very least, articulated an agenda for what we expected of the information society, and, as a result, an agenda for what came to be expected of communication studies departments, which was, to be reductive, the preparation of students for a new economy of changing media technology. This agenda has an uneven intellectual legacy. I’ve seen smart people led astray by Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man (1964) and The Gutenberg Galaxy: The Making of Typographical Man (1962), taking far too seriously their prognostications. I’ve seen how McLuhan’s ideas can mystify and seduce students into unproductively deterministic and evolutionary thinking about media. And I’ve seen arguments about technological change get bogged down in McLuhanesque ahistorical claims that rule out resolutely engaged questions about material conditions. McLuhan might help some people think about the long view of human civilization–or better yet, eternity–but he’s slippery at best when it comes to the specificities and complexities of the lived time horizon we actually inhabit.

Having laid my cards on the table, I still read him and read about him, in part because in his work and life one encounters the formation of some major priorities of our time. Depending how you count, I’ve just finished my third or fourth biography of him, this one by the key organic intellectual of Generation X, Douglas Coupland, who is, in his own way, an agenda-setting voice.

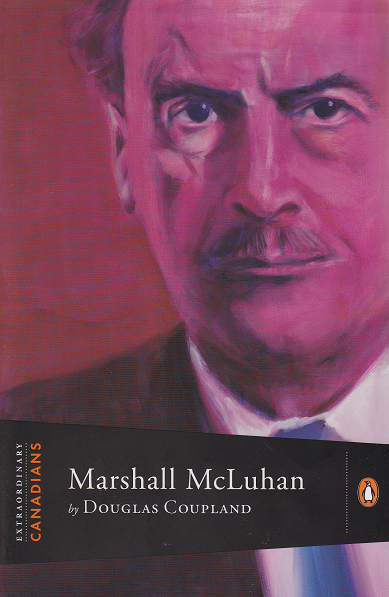

Marshall McLuhan (2009) is part of John Ralston Saul’s “Extraordinary Canadians” book series, which assigns historically prominent Canadians to contemporary celebrity writers who compose short accessible biographies. The famous subjects selected for the series betray a left-leaning progressivism, including such north-of-the-49th household names as Louis Riel, Emily Carr, and Tommy Douglas. This progressivism matches one strong, and frankly appealing, strain of national self-mythologization, but it also suppresses the brutal and stultifying aspects of what is as exploitive an advanced industrial society as has ever existed. The apolitical McLuhan stands out, then, from the generally progressive figures in Saul’s book series as a by-standing grandstander among engaged intellectuals, artists, and politicians. For this reason, McLuhan is a fine representative of the self-interestedness of Canadian cosmopolitanism.

To accomplish the assignment Saul gave him, Coupland takes on the language of ephemerality and randomness. He treats McLuhan’s books as collectible commodities for sale online at Abe Books, reprinting listings including the price and condition of each item. He offers pages of anagrams of the most famous McLuhanism–“global village,” “the medium is the message”–which become brief lessons in pattern recognition. And he displays uncertainty about the status of the biography and its presumption of a unified subject. So concerned is he about this status that no biography in publishing history, I’d wager, has displayed such deference to anonymous or unedited web-postings about the individual being researched. For example, behind a cover boasting an artfully impressionistic portrait of McLuhan and on crisp 30% recycled paper stock, Coupland refers the reader to the Wikipedia entry for Understanding Media rather than elaborating on that book himself.

Coupland employs these tactics to explore the border between the print culture of the book and the digital culture of the Internet. Marshall McLuhan becomes an exercise in how one goes about a literary task in McLuhan’s post-literate era. Coupland’s poetic rendering begins with McLuhan in his final days, ravaged by a stroke that left him without speech, freeing a bee trapped in his office while muttering “boy oh boy oh boy.” Bees are the topic of Coupland’s most recent novel Generation A (2009), excerpts of which he includes here in short stories that, as readable as they are, leave you with the impression he needed more pages to fulfill the contract. These are among the more pedestrian turns in Coupland’s standard issue self-reflexivity. More evocative is the closing segment, in which he stretches from McLuhan’s early days in Alberta and Manitoba to Coupland’s own grandfather, traveling great distances across the limitless horizon of the Prairies to sell concrete during which, as Coupland imagines, he contemplates the very nature of space and modernity.

The sweep of the narrative of McLuhan’s life remains fascinatingly specific to the post-WWII context, and the story of the transformation of the Cambridge trained literary critic into an oracle of our information society is a wonder to re-visit. As Coupland captures, through a decade-long rehearsal and distilment of the works of Harold Innis, Ted Carpenter, and Siegfried Giedion, to name but three of his major influences, McLuhan arrived at an intellectual strategy that condensed complex observations into alternately pithy and baffling aphorisms. By the beginning of the 1960s, he had a large inventory of such statements, which he then spun out and re-combined for the next two decades hampered only by health issues and, in my view, his virtual inability to write substantive works on his own after 1964.

But consider this: one million copies. That’s the sales figure for The Medium is the Massage: An Inventory of Effects (1967), the short photo essay consisting of statements from McLuhan with counterpoint images, curated and designed by Jerome Agel and Quentin Fiore. One million copies. Has any other media theorist been able to have this kind of popular reach, as measured by book sales? In the futurist camp, one might include a figure like Alvin Toffler and his book Future Shock (1972). But for media theorists specifically, this must be a unique achievement. McLuhan’s Understanding Media was a 1964 must-read, topping 100,000 copies. But one million!

It is here that we find the value of this biography and of re-considering McLuhan in general. Coupland elegantly draws out how foundational McLuhan was to the way we think, talk, and aspire to live in a mass-mediated world. McLuhan’s work, and importantly its popularity, set in place core qualities of the electronic age and he made the orientation of our world toward new media seem inevitable. In this way, McLuhan bears considerable responsibility for easing our entry into the digital era. Obviously, this was not his responsibility alone, and, as I mentioned, his ideas and concepts find their origins with other writers. But his influence was so great that he functioned to establish an everyday understanding of, and set of priorities about, the upheaval of contemporary society. McLuhan is part of the vernacular of our media environment.

For this reason, you still hear people claiming he “predicted” later technological developments, in particular the Internet. Coupland tempers this tendency, though he can’t entirely help himself and settles on the slightly less psychically inflected “foresaw.” Instead, I would suggest, McLuhan made sure we would be talking about something that we later ended up calling the Internet. He put an idea about the instant and abundant global movement of media messages on our collective agendas as though it was specific to the latter half of the 20th century (which most media historians will quickly point out it was not). Whether he was right or wrong in his statements about media strikes me as beside the point. An obsession with a new sensorium associated with global universalism, immediacy, mobility, individuality, immateriality, and technological change defined the coming decades, domesticating an economic and industrial regime as inevitable and natural.

And this is the heart of McLuhan’s political legacy, not the actual claims about different media, but McLuhan’s vision of imminent change, that there were such changes written into the deep code of media, and that the changes were preordained and unstoppable. Refusal was no longer an option. It may seem odd to suggest, but the confusing and logically shaky claims of McLuhan became a kind of commonsense in the context of the first era of computers. His dominant, pervasive, and contradictory ideas made it that much more challenging to account for the full cost this global transformation has exacted on our environment, economy, and civil society. So by returning to McLuhan, you return to a point of consolidation, and popularization, of the technological imperative of global change, an imperative that we have recklessly allowed to occupy our imagination of what society and culture might be. Yes, McLuhan is alive and well and writing ad copy for Cisco Systems, apps for iPhone, and artist grants for new media installations.

Further Reading:

Cavell, Richard. McLuhan in Space: A Cultural Geography. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2002.

Coupland, Douglas. Marshall McLuhan. Toronto: Penguin, 2009.

Marchessault, Janine. Marshall McLuhan: Cosmic Media. Thousand Oaks: Sage, 2005.

Author’s note: Thanks to Haidee Wasson for commentary.

Image Credits:

1. Close-up of the Marshall McLuhan book by Douglas Coupland.

2. Cover of the Marshall McLuhan book by Douglas Coupland.

3. Author screen capture.

Please feel free to comment.

Charles,

This piece raises a really great question, particularly as McLuhan (and his writing) becomes seemingly both more and less important as we move into the heart of the digital era. I really like how you have highlighted this ongoing conflict between what we think McLuhan stands for, and what he ended up eventually coming to stand for.

I think that by focusing on the contradictions inherent in Douglas Coupland (a celebrity himself) you have hit the nail on the head when you highlight that McLuhan’s ideas moved not only into the larger media sphere and into an even larger context, as well as addition to selling a staggering amount of books.

For me, my impressions of McLuhan exist in his public appearance in Annie Hall and his thinly veiled representation in David Cronenberg’s Videodrome, where the pre-taped Brian O’Blivion talks about the utopian dimensions of the coming video era. This public recognition, if only for his famous, oft-repeated and fairly cryptic “the medium is the message,” seems representative of a fairly unique moment of our contemporary intellectual history. Perhaps part of the difficulty of coping with McLuhan’s enduring status also stems from this particular moment within media, which stands as a high watermark of intellectual discourse in the public sphere (at least on TV), as McLuhan’s various talk show appearances (on places like PBS, Dick Cavett’s show) made way for the war of images (or at least john Stewart caling out the pundits on Crossfire) and the impoverishment of dialogue and debate.

The fact that McLuhan’s image persists in our contemporary culture, if only in these representations (and perhaps in Coupland’s book) is testament to his persistence in the media that he predicted would become increasingly important.

All of which is to say that this article raises way too many thoughts to coherently account for all of them. Thanks again for reminding us about this prominent thinker and our indebtedness to his pioneering work.

Pingback: McLuhan links « new media seminar (jmc 860)

Pingback: The Children of Chuck Barris: Reality TV in the 1970s R. Colin Tait / FLOW Staff | Flow