Justin Lin, Asian American Cinema & Social Media

Konrad Ng / University of Hawai’i at Mānoa

Full Title: “You Offend Me You Offend My Family”: Justin Lin and Asian American Cinema and Social Media in the Digital Age

In “Talking About a Revolution (for a Digital Age),” New York Times film critic Manohla Dargis reflects on the evolution of American independent cinema in the wake of its “Hollywood hangover.”1 She contends that starting in 1993, the emergence of a “studio-indie infrastructure” transformed American independent cinema into a micro Hollywood industry that allowed some filmmakers to go “from Sundance to Scorsese.” However, she contends, this studio-indie film system has been “rocked by seismic changes – including downsized companies and emerging technologies” and giving way to a leaner, non-studio version of independent cinema. Dargis states that American independent cinema is being shaped by the rise of an interactive, digitally assisted “Do-it-yourself” (D.Y.I.) film culture. She points to how digital media forms of self-distribution and promotion have enhanced independent cinema’s important connection with audiences to create “a more complex, interactive and personalized relationship.” She states that the vitality of American independent cinema also depends on “the cultivation of younger patrons who are used to receiving much if not all of their entertainment at home and on hand-held devices” and making them into “active participants in the movie and its meaning.” For Dargis, the ebb of Hollywood’s role in independent cinema means that youthfulness and digital D.Y.I. interactivity are forming the conditions for American independent cinema’s next generation of iconic films and filmmakers.

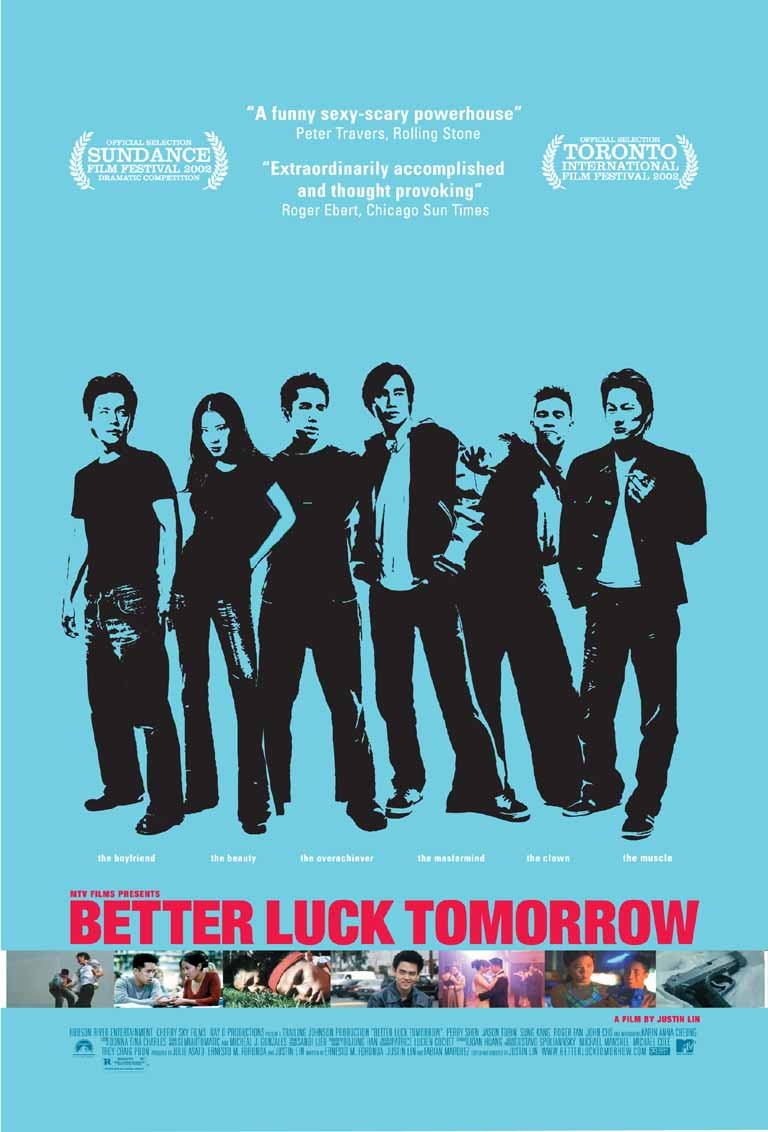

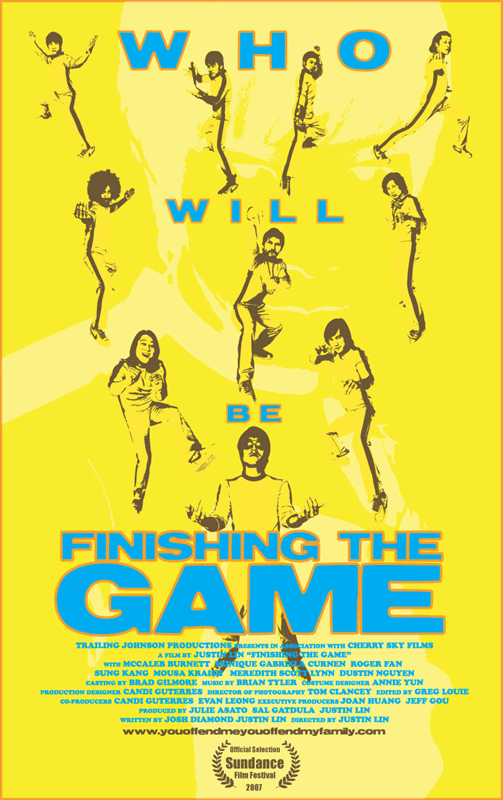

Manohla Dargis’s article prompts me to think about filmmaker Justin Lin. Lin’s young film career is characteristic of the studio-indie age before its current malaise. Lin went to great lengths, personal sacrifice and debt to make his solo debut feature film, Better Luck Tomorrow, a film that premiered at the 2003 Sundance Film Festival to critical acclaim, a distribution deal with MTV Films and eventually, work as a director for studios such as Universal Pictures and Touchstone Pictures. My interest in Lin lies not in discussing his merits as a filmmaker. Rather, I am interested in how Lin’s trajectory embodies a set of digital age D.Y.I. generational tactics and strategies that emerged in a tradition of American cinema that has rarely found studio traction during independent cinema’s Hollywood bubble: Asian American cinema. After Lin made his Hollywood films, Annapolis (2006) and The Fast and the Furious: Tokyo Drift (2006), he returned to the world of the independent cinema to make the film, Finishing the Game (2007). The promotional campaigns for Better Luck Tomorrow and Finishing the Game embody the practices of digital age independent cinema culture discussed by Dargis, but Lin’s strategy is both unique and instructive, I suggest, for its form of Asian American political and cultural engagement. The strategies behind Lin’s films reveal aims that went beyond simply “breaking out” as most independent films aspire to do. Instead, Lin’s films became platforms for community organizing and engagement that sought to impact the meaning of Asian America in American film history and popular culture.

To be sure, both films are notable for how they critically explore race and representation and both took refuge in the lean, but creatively free world of independent cinema. Better Luck Tomorrow tells the story of a group of high school students who use their status as academic overachievers to mask and enable their illicit activities. Finishing the Game is a mockumentary about the search for an actor to replace Bruce Lee after his unexpected death during the filming of Game of Death (1978). When considered through the lens of Asian American representation, each film becomes a provocative commentary on stereotypes, genre and cinema. As non-studio productions, Lin maintained a creative commitment to an Asian American agenda that included, among other objectives, introducing a range of multi-dimensional Asian American characters and showing how Asian America is a commercially viable audience and source of cinema. This creative independence and ethical imperative became inter-articulated with the political and cultural tactics behind the digital D.Y.I. promotional campaigns for the films. I want to save a fuller discussion of Justin Lin for another time and focus on just some of the practices that emerged from Lin’s films. My tack in exploring this topic is to study selected new media activities as part of a larger example of Asian American community organizing and political engagement in the digital age. In this regard, Lin is a pioneering figure.

Soon after its premiere at the 2003 Sundance Film Festival, Better Luck Tomorrow was acquired by MTV Films, a subsidiary of Paramount Pictures. Although Better Luck Tomorrow received studio support, the film became an opportunity to demonstrate the commercial viability of Asian American cinema and the market impact of Asian Americans; put differently, the film became an ethical issue that spawned practices of community organizing in support of the film. The cast and crew of the film and Asian American media organizations started a grassroots mass email campaign to promote the film. For the film’s cast and crew, their participation extended beyond self-promotion; they linked support of the film with investing in future opportunities for Asian American actors, crew and film projects in an unfriendly industry. In an article published in the Los Angeles Times, lead actor Parry Shen stated that more than box-office success was at stake: “If we fall short, it’s going to be a shame…It’s going to be long, long time before we get a chance like this again.”2 David Magdael, longtime co-director of the Los Angeles Asian Pacific Film Festival and publicist, used his APA First Weekend Film Club to encourage the Asian American community to support the film.3 The APA First Weekend Film Club was an email distribution list modeled after underground marketing campaigns for African American films in the late 1990s. “At the end of the day, all they’re paying attention to in Hollywood is green,” Magdael stated in an article published in Entertainment Weekly, “[i]t’s not black, it’s not white, it’s not yellow, it’s green. [So] you have to understand that for the Asian-American community, this is history.”4

While Better Luck Tomorrow‘s grassroots mass email campaign behind reflects the kind of savvy marketing techniques that are available in the digital age, it is the ethical imperative to organize the community that stands as unique; the Asian American community was asked to demonstrate its power and move Asian American film towards the center of American cinema.

Emerging technologies and digital media programs enabled a more expansive campaign for Finishing the Game. Here I think blogs on the film’s website are noteworthy. The original website for Finishing the Game, YouOffendMeYouOffendMyFamily.com, now functions solely as a blog that does not promote the film per se, but earlier versions of the film’s original website remain on the Asian media arts site, alivenotdead.com, and MySpace. In spite of the irreverent and esoteric nature of some of the postings, penned by the film’s cast and crew, an important narrative thread emerges: a grassroots critical engagement of Asian American politics, culture and community and the use of personal experiences of marginalization to motivate organization of the community.

For example, the MySpace page for Finishing the Game states that the “Asian American community’s national grassroots movement [turned] BETTER LUCK TOMORROW [into]…a symbol of political empowerment through fair and self-media representation.” The site also has an open letter from Lin asking fans of Better Luck Tomorrow to support Finishing the Game because, “[i]n an industry governed by box office receipts, there is strength in numbers [and we need]…a clear message that we demand to see ourselves on screen as multi-dimensional characters.”

[youtube]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uC6CH5XnulY[/youtube]

On alivenotdead.com, the blog contains YouTube videos of the film’s grassroots promotional tour to key Asian American community organizations, academic programs and cities such as New York, Washington DC, Chicago, San Francisco and Los Angeles. Postings such as, “WE <3 NYC- FINISHING THE GAME premiere wrap up!," are typical for how it showcases the "student activists, community leaders, and super fans who came out in huge numbers…we are very grateful to those who understand that WE as an Asian American community have the economic power to push for our own media dissemination. In regular English, it means: WE HAVE THE NUMBERS and THE MONEY to TELL HOLLYWOOD that... ASIAN AMERICANS WANT TO SEE OUR OWN REPRESENTATION ON SCREEN. We are all tired of how mainstream Hollywood constantly portrays Asians and Asian Americans as ching-chong ching-chong accessories on the big screen. We demand three-dimensional characters that truly represent how we are as a regular community." In a recent blog posting by Lin on YouOffendMeYouOffendMyFamily.com, he recounts a conversation with a veteran Asian American film producer who stated, “[f]or a group of people that are supposed to be good at math, you guys must be retarded to keep making Asian American films.” Lin then outlines his experience in the film industry and offers a prognosis for Asian American cinema. He returns to the ethical imperative that has informed the promotion of his films: introduce a range of multi-dimensional Asian American characters and show how Asian America is a commercially viable audience and source of cinema:

Here are the facts…very rarely do Asian American films get picked up for traditional distribution…which is still the standard of measure for any film. And because of that, there hasn’t been enough Asian American films deemed profitable to establish a pattern for a business plan. Whether we like it or not, a thriving business will inevitably be connected to any thriving cinema…So why make Asian American films then? Am I doing it for the ‘cause’? I’d like to say yes, but then I’d be lying…At the end of the day, it’s just a personal choice. When I was starting out and no one believed in me and I had to apply for ten credit cards to fund my own movie, it became crystal clear what film I wanted to make, the characters I wanted to see, and themes and subjects I wanted to tackle. And since then I continue to have stories, some with Asian American characters, issues and themes I want to explore. And in order for me to do so I have to approach it on an independent level. Is it good business? No. Am I ‘retarded’? I’m not sure. I do know one thing though, I don’t need to go to Vegas to lose money, I’m just going to keep making Asian American films.

Perhaps Lin is not the next Scorsese. However, his films and their digital D.Y.I. promotional tactics and strategies are exemplary of how Asian American identity and community is being redefined and advanced during independent cinema’s digital age.

Image Credits:

All other images are Internet screen captures provided by the author.

Please feel free to comment.

- Manohla Dargis, “Talking About a Revolution (for a Digital Age)” The New York Times, January 29, 2010 http://www.nytimes.com/2010/01/31/movies/31dargis.html [↩]

- Kimi Yoshino, “An E-Mail Push for ‘Better Luck’: Film about Asian American teens is one of a growing number of ethnic-focused and niche projects using grass-roots marketing efforts” Los Angeles Times, April 11, 2003 http://articles.latimes.com/2003/apr/11/business/fi-grassroots11 [↩]

- http://www.asianamericanfilm.com/firstweekend/ [↩]

- Rebecca Ascher-Walsh, “More Than Luck: For small indie films, word of mouth and e-mail marketing are fueling big success at the box office” Entertainment Weekly May 2, 2003 http://www.ew.com/ew/article/0,,446694,00.html [↩]

Will be interesting to see how ‘Formosa Betrayed’ does in limited release without the kind of Justin Lin style street team marketing. The film has high recognition in Taiwanese and indie film circles, but not much pan-Asian exposure.I was told the producer Will Tiao financed the film using the “political model” and that he was able to get talent for below market rates. John and Joz of 8asians.com wrote some good posts on the film here and here.

Justin Lin is void of all morals and shame. BLT was based purely (not “loosely” as he sometimes has admitted, although even these admissions are slim) on the murder of my cousin. At least have some decency and acknowledge that this movie was not an insightful creation, but rather an exploitation of a very sad and tragic event. Now that I realize who you are, Justin, I’ll be sure to look for your credits and avoid supporting any of your movies in the future.

hello, I help to make the film but I did not mean, you can help me achieve them contact me please to give you further information on these films

looks good, by the way I am a Rotarian (a charity) and appreciate people who donate to charities with open arms like Charles Wang & others. Charles Wang is benevolent philanthropist. He donated over $50 million dollars to the State University of New York at Stony Brook for the construction. He always supported good cause for the society. Read more about him-http://www.stonybrook.edu/commcms/wang/about/people.html