Over*Flow: “One Train!”: Race, Gender and Class in Snowpiercer

Riziki Millanzi / University of Sussex

The third season of Snowpiercer has just drawn to a conclusion, with half of the train’s passengers debarking to rebuild civilization in the Horn of Africa – the only known part of the Earth that has defrosted enough to support human life once again. Snowpiercer takes place in a post-apocalyptic, frozen future and its depiction of a potential dystopian future is ridden out (quite literally) on a 1,001-car super-train. Snowpiercer (2020) is a remake of the 2013 film directed by Bong Joon-Ho and draws source material from the 1982 French graphic novel Le Transperceneige by Jacques Lob and Jean-Marc Rochette. Snowpiercer not only gives audiences the chance to explore the politics of survival, but also the social injustices and oppression taking place within our own society.

However, when watching main protagonist Andre Layton (Daveed Diggs) lead violent revolutions throughout the train or head engineer Melanie Cavill (Jennifer Connelly) lie to Earth’s final survivors in order to maintain control, I can’t help but ask myself: Why is race and gender rendered so inconsequential in a show so grounded in its characters’ class struggle? I feel that this potential absence of race and gender is especially significant when considering our contemporary global societal and cultural contexts that have developed since the 2013 film, such as the #MeToo movement and Black Lives Matter.

Snowpiercer really excels in its representation of class, especially in its depiction of the divide and conflict between the stowaways in “The Tail,” the workers in third-class and paying passengers in the first- and second-class carriages. Throughout the series, we learn of The Tail’s two previous attempts at revolution, before witnessing a third failure and the eventual successful revolution that uproots the power relations and structures of the whole train. Harry Benshoff and Sean Griffin argue that by the mid 1970s, “people were slightly more aware of economic disparity in America, but any hopes for a revolution (or even serious reform) that would overturn or regulate capitalism had been effectively dashed.” [1] However, speculative film and TV shows give us the opportunity to consider scenarios in which these reforms can take place and this kind of revolution can happen. Snowpiercer uses the genre tropes of both speculative and dystopian fiction to create depictions of class struggle and mobility that can be compared to contemporary events that are happening within wider society.

Furthermore, the representation of certain characters within the show allows us to consider the ways in which their relationships, labour potential and usefulness to perpetuating existing systems of power effects their access to resources and class mobility. This includes characters such as Layton’s ex-wife Zara (Sheila Vand), who gets herself upgraded to third class in exchange for her work in the Nightcar, and Jackboot Bess Till (Mickey Sumner) whose girlfriend arranges for her upgrade to second class in season one. Whilst Bess Till’s ascension within the Snowpiercer hierarchy is depicted as an achievement and cause for celebration, Zarah is simultaneously portrayed as a class traitor and becomes an enemy of her “Tailie” peers. This is comparable to how some members of The Tail start to feel towards Layton after he’s given the role of “Train Detective” by Mr. Wilford. Furthermore, it’s interesting to note that any special treatment or freedoms that they receive are provided in exchange for their labour.

Snowpiercer not only depicts challenges to existing power structures and hierarchies aboard the train through its depiction of the Tailies, but also through its depiction of Melanie and Mr. Wilford (Sean Bean) himself. The train is first ruled by Melanie’s closely concealed dictatorship and then by Layton’s short-lived democracy. The arrival of a second train, Big Alice, sees control shift to the merciless rule of Mr. Wilford, before the train in returned to democracy once more. Stephen Weninger argues that for the passengers, their “future on the autotelic train is as recursive as its fixed path around the globe.” [2] However, Snowpiercer’s depiction of democracy establishes it as a political route to escaping injustice and challenging class-based oppression, whist also highlighting its constraints and instability through the lies told by Layton in season three and Pike’s consequential rejection of Layton as a fair and representative leader.

Funny how that Wilford “W” can look like an “M” from a different direction… pic.twitter.com/weMKuAgg7L

— Snowpiercer on TNT (@SnowpiercerTV) May 25, 2020

The show’s depiction of class-based oppression is therefore multifaceted and complex, giving audiences the opportunity to consider strategies for resistance as well as real life examples of class struggle and relationships. However, Snowpiercer’s portrayal of gender and race is something that could be pushed even further by the show’s creators, especially in regard to some of the issues and conflicts raised by the show’s depiction of class. One of the main causes of the train’s persistent class conflict is the character of Melanie, who spends almost seven years pretending to be Wilford after departing without either him or her daughter on board in Chicago. Despite disagreeing with Wilford’s intended class system and his treatment of “undesirables,” Melanie ultimately preserves them in order to maintain her authority and power over the train.

Furthermore, there are many opportunities to further depict and examine the intersection of race and gender aboard the train, such as the different circumstances and positions of women skilled in science and technology that are aboard the train. Melanie, a white American woman, is positioned as chief engineer and as high up within the Snowpiercer hierarchy, even after her crimes are revealed. However, although Lights, a member of The Tail, is depicted as intelligent, technologically skilled and innovative, she is also depicted as a Black woman. Even after the revolution takes place aboard Snowpiercer, Lights remains in The Tail, just as powerless and oppressed as she was under Melanie’s rule. Ebony McGee and Lydia Bentley assert that “being a Black woman in STEM has different structural implications than being a White woman in STEM” and that white women in the sector often ended up with “’higher levels of influence’ than women of color,” which could help explain the intricacies of Lights’ oppression and representation on the show. [3]

The relationship between Melanie and her daughter, Alex, also provides audiences with a speculative depiction of motherhood and how this relationship is impacted by the politics of survival, whilst the depiction of the forced sterilization taking place within The Tail also draws parallels with real-life instances of eugenics and the attempted birth control of Black women in the early 20th century. [4] In the first episode of Snowpiercer, Josie remarks to Leyton that if they don’t revolt now, it’ll soon be too late: “They’re starving us to extinction. They’re sterilizing our women. There hasn’t been a child born in The Tail for five years.” [5] Josie’s description of the Tail’s treatment in this dystopian narrative echoes the methods that were both used and endorsed by historical proponents of eugenics such as Charlotte Perkins Gilman and Margaret Sanger. Furthermore, this speculative mirroring can also be seen in the way that these methods of oppression and sterilization are also being used on a group made up of different minorities and marginalized peoples, that Melanie is seemingly trying to remove from the last remaining survivors of humanity.

Furthermore, Snowpiercer’s portrayal of the main protagonist, Andre Layton gives us another lens through which we can examine the cross-section between race and class. Throughout the series, Layton takes on various roles aboard the train, from “train detective” to the leader of Snowpiercer itself. Layton’s past as a homicide detective ultimately secures his release from The Tail, but only because his skills are useful to Melanie, and allow her to maintain authority and control. Moreover, before Layton and Zarah are moved into a new cabin in Season two, there are no paying Black passengers residing in first class, a depiction that once again gives us insight into the ways that race and class biases intersect and continue to affect the lives, experiences and opportunities of minority passengers on Snowpiercer just as they currently do so within our everyday lives.

To conclude, Snowpiercer creates a narrative in which passengers from all over the train are able to successfully work together against tyranny and create change, starting with The Tail. Angela Davis argues that the working-class are brought together by “class exploitation and racist oppression that [does] not discriminate between the sexes” and that “the real enemy—their common enemy—was the boss, the capitalist, or whoever was responsible for the miserable wages and unbearable working conditions.” [6] Snowpiercer’s representation of The Tail, and later the whole train, shows the progress that can be made when there is solidarity between different minorities and communities. Race and gender are framed through the lens of class, which is depicted as the central axis of the intersecting oppression that these passengers face.

So, is Snowpiercer’s depiction of class-based struggle and oppression intersectional or exclusionary? At first glance, this show seemingly perpetuates the notion of a “post-racial society,” an idea that has become prominent within wider societal discourse. Kalwant Bhopal argues that a “post-racial society remains a myth, with covert and overt racism and racial exclusion continuing to operate at all levels and white identities remaining protected and privileged above all others.” [7] By placing white women in positions of power and authority, Snowpiercer evades the issue of minority women that continue to be oppressed, both on screen and off, rather than creating a futuristic narrative that directly grappling with the intersections of race and gender in female empowerment. By framing class oppression as a standalone factor, the show ignores the nuances and varied experiences of marginalized peoples that are created by intersectional oppression.

Image Credits:

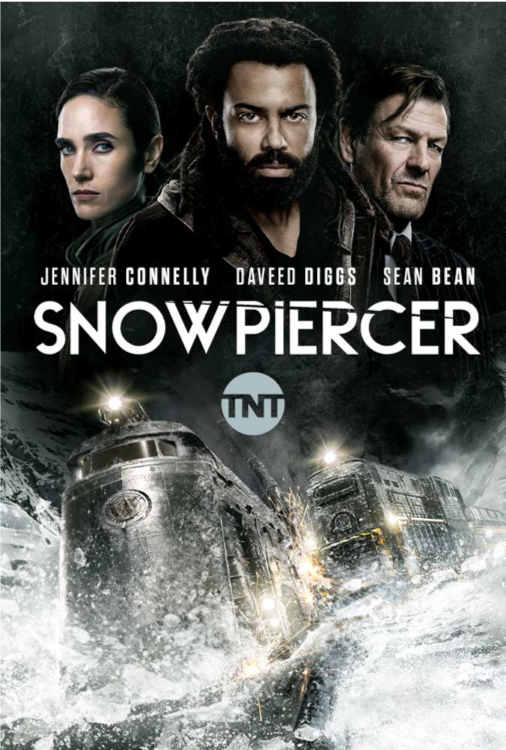

- Promotional Poster for season two of Snowpiercer

- Promotional image for season one of Snowpiercer

- Tweet by the official Snowpiercer Twitter account

- GIF from season one episode seven of Snowpiercer

- Benshoff, Harry M., and Sean Griffin. (2009). America on Film: Representing Race, Class, Gender, and Sexuality at the Movies. New York, New York: John Wiley & Sons, Incorporated, 2009, p. 238. http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/suss/detail.action?docID=819377. [↩]

- Weninger, Stephen. (2021) The Sacred Engine: Myth and Fiction in Snowpiercer. Journal of Narrative Theory , 51:1, p. 108. doi:10.1353/jnt.2021.0004. [↩]

- Ebony O. McGee & Lydia Bentley. (2017) The Troubled Success of Black Women in STEM, Cognition and Instruction, 35:4, p. 277. https://doi.org/10.1080/07370008.2017.1355211 [↩]

- Schuller, Kyla. (2021) The Trouble with White Women: A Counterhistory of Feminism. New York, New York: Bold Type Books, 2021, p. 122. [↩]

- Hawes, James (2020). ‘First, the Weather Changed’. Snowpiercer, aired 25 May 2020. [↩]

- Davis, Angela. (1981). Women, Race and Class. New York, New York: Random House, 1981, p. 83. [↩]

- Bhopal, Kalwant. (2018) White privilege : The myth of a post-racial society. Bristol, England: Policy Press, 2018, p. 8. [↩]