8-Bit Porn: Atari After Dark

by: Eric Freedman / Florida Atlantic University

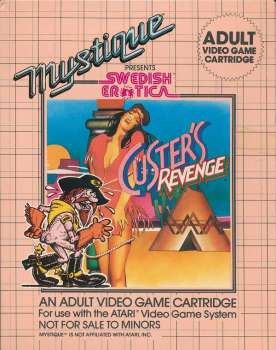

In the game manual for their 1982 release Custer’s Revenge, Mystique entertainment proclaims, “The world of electronic video games is a most exciting concept. It uses computer-generated images to challenge the player’s imagination; to create a fantasy situation that offers a challenge. We at Mystique feel that it’s time for video games and their adult players to come out of the closet, away from the kids, and deal with ADULT fantasies. Our own team of design engineers has developed a line of games that don’t just stop at ‘Adult’, but push the Atari console to the limit.”

I grew up with Atari, and with my nostalgia getting the better part of me, I recently purchased two 2600 systems on eBay—a 4-switch wood grain console manufactured in 1980 and a first generation 6-switch console known by collectors as the “heavy sixer”. The Atari VCS CX2600, introduced in October 1977, is an 8-bit system that uses interchangeable cartridges; this was an innovation in the 1970s, because as the cartridge replaced the dedicated console, gamers could play the latest games without purchasing a new system. As one of its strategies for marketplace dominance, Atari actively pursued licenses for successful arcade games, beginning with its home version of the popular shooter Space Invaders. Arcade conversions and top-notch third-party titles by companies such as Activision (a company formed by disgruntled Atari programmers that became a significant competitor in the cartridge market, but nonetheless furthered Atari’s temporary hardware dominance) helped Atari gross significant profits in its first five years. But Atari’s prominence came to an end with the video game crash of 1983. When the market re-stabilized in the second half of the decade, the Japanese company Nintendo took center stage. Unlike Atari, Nintendo instituted a very strict licensing system for third-party game developers and heavily controlled advertising, distribution, production, and pricing in an effort to control quality and profit.

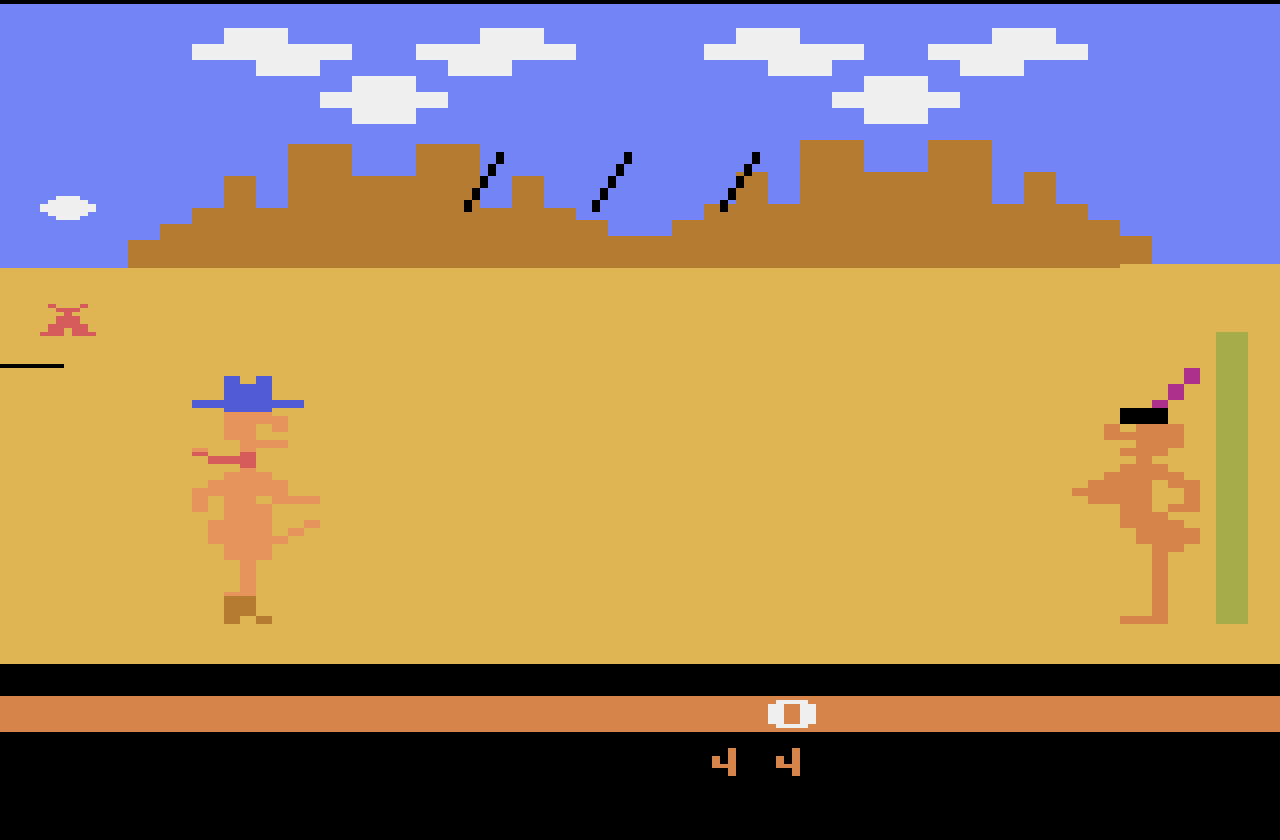

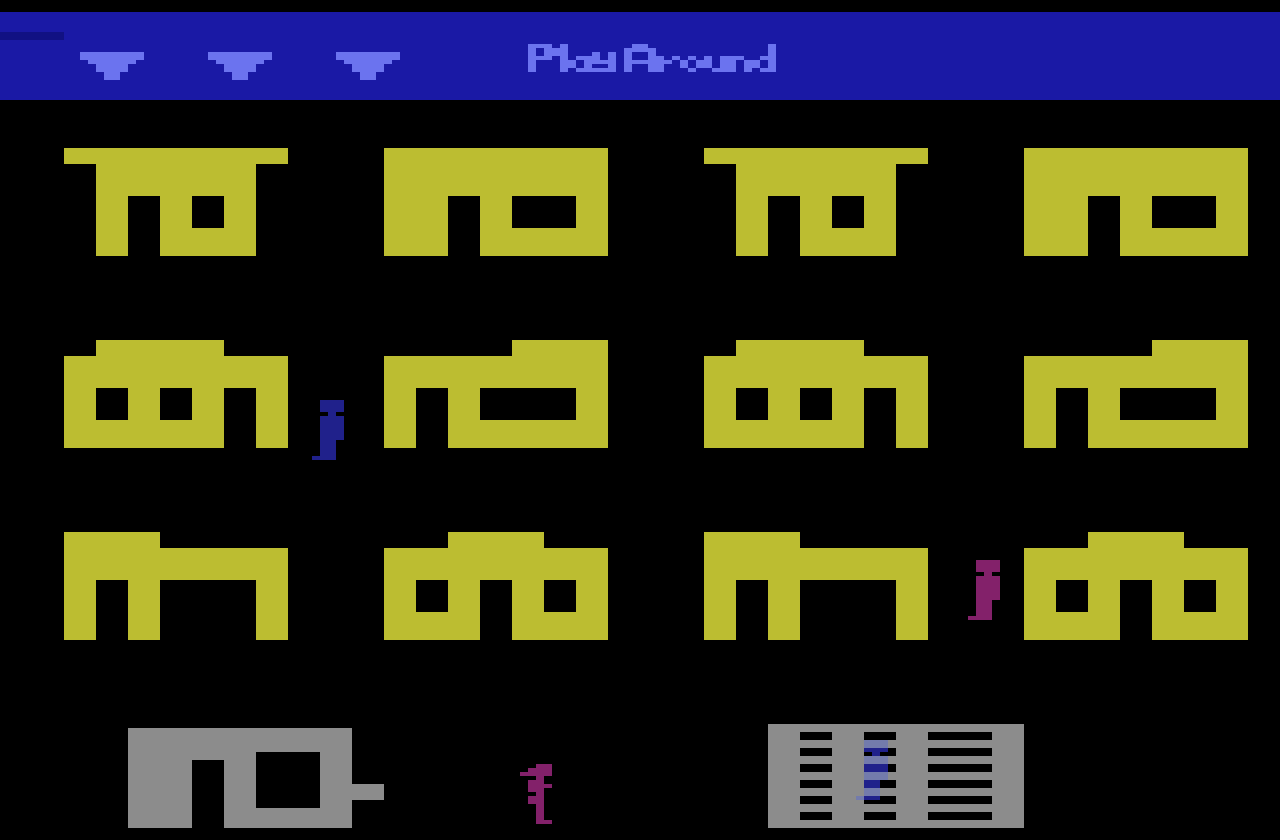

My knowledge of the varied third-party Atari titles that I did not own in my youth is primarily gleaned from emulation and ROM sites. Programs such as Stella, a multi-platform Atari 2600 VCS emulator, allow PC users to play arcade ROMs (read only memory chips) on their personal computers. The role of the emulator is to mimic hardware functionality with software, while the ROMs themselves circulate freely on the Internet as image files, which contain the actual data and code read from the original cartridge. Scattered throughout various ROM sites are a number of adult titles designed to play on the 2600, extracted from game cartridges produced by three companies—Mystique, Playaround, and Universal Gamex. While I am not the first enthusiast to sketch out the basic lineup of adult titles designed to play on 2600 consoles, what most of the fan sites do not consider is the role these games may have played in larger industrial and cultural discourses about gaming. Most discussions focus on the rather crude graphics and underwhelming game play of these titles, many of which simply rework the basic functionality of more popular mainstream games, and replace the regular cast of characters with the grossly pixilated bodies of naked men and women; perhaps to ensure the legibility of these characters, the pixel-based construction birthed rather absurd anatomical distortions. Other discussions focus on the obvious sexism written into the gendered biases of these games; most of the rudimentary narratives climax with the requisite frenzied pushing of the joystick fire button, a gesture that produces on-screen penetration and its off-screen thumb-pulsing corollary.

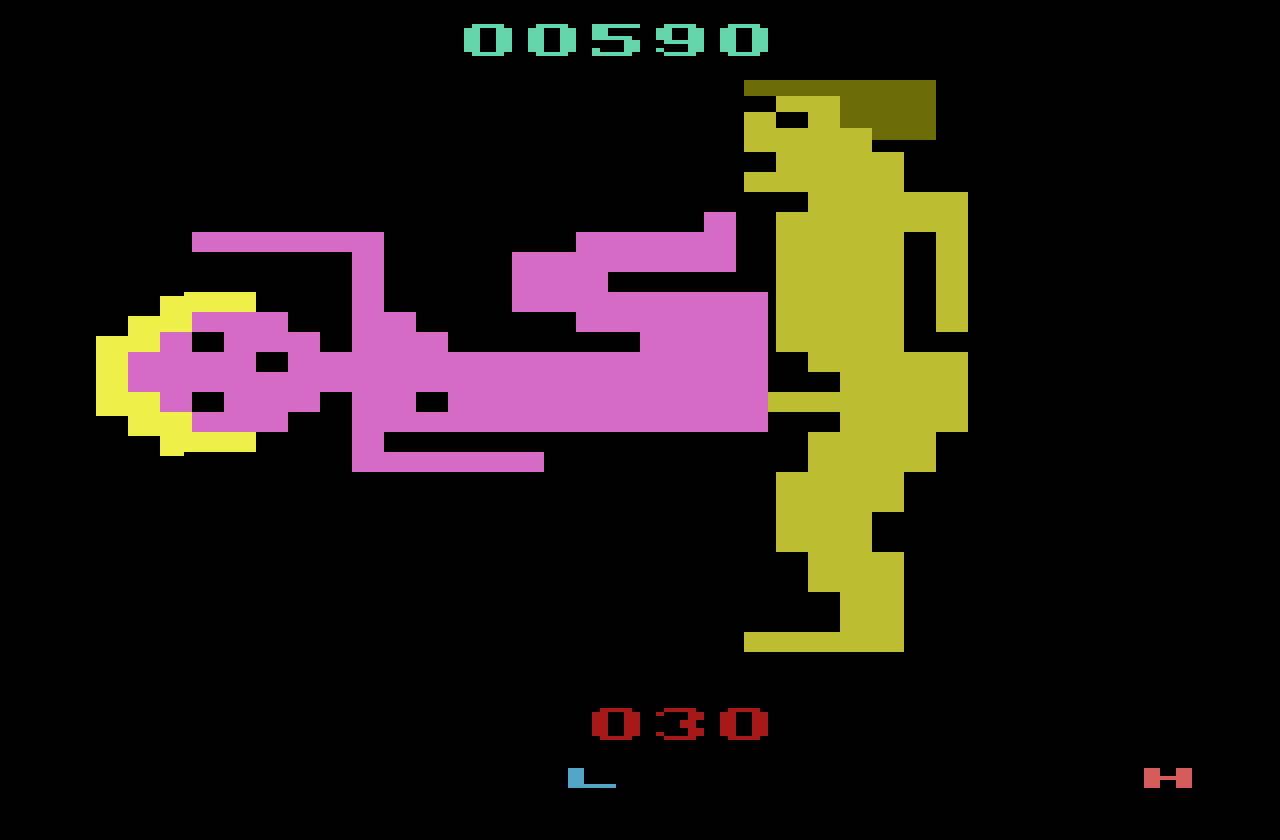

Screen shot from Custer’s Revenge

Mystique produced a number of adult video games for the Atari 2600 in the early 1980s. Formed in 1982 as an offshoot of the adult film company Caballero Control Corporation, and the parent company American Multiple Industries, Mystique’s games were sold under the “Swedish Erotica” banner, capitalizing on the brand attached to an already successful adult film series. Custer’s Revenge is perhaps the most notorious Mystique title. The player guides a rather erect General Custer (wearing only a cowboy hat, boots and neckerchief) across a desert screen; dodging a hailstorm of arrows, Custer’s goal is to reach a Native American woman tied to a post on the other side. After successfully navigating the onscreen obstacles and reaching the woman, the player frantically pushes the joystick’s fire button to score points for each time Custer penetrates her. The game prompted complaints from a number of groups at the time of its release; a product demonstration at the New York Hilton in October 1982 attracted protestors from the National Organization for Women, Women Against Pornography, American Indian groups, and the Racial Justice Committee of the National YWCA; the game received scathing criticism for denigrating women and offering rape as a reward. Not surprisingly, Atari sued Mystique over the game, claiming that its releases were tarnishing the brand; Atari argued that American Multiple Industries had failed to adequately disassociate itself from Atari and was capitalizing on the name and trademark. Learning from Atari’s mistakes, when Nintendo launched the NES system in the United States at the end of 1985, the company’s “lockout” technology placed significant restraints on third-party developers.

Despite Atari’s lawsuit, Mystique produced several more titles before going out of business during the video game crash of 1983. Playaround, a spin-off company that continued the adult game line, acquired the rights to the Mystique games. In addition to manufacturing double-enders, or extra-long cartridges of Mystique titles that had a different game on each end, Playaround created re-gendered versions of several games, reversing the gender roles of the central characters, presumably in an attempt to attract male and female game players to parallel titles (while minimizing redesign costs). Philly Flasher redressed Mystique’s Beat ‘Em and Eat ‘Em, Bachelorette Party complemented Bachelor Party, and General Retreat tied Custer to the stake while the female character traversed the screen avoiding enemy cannonball fire. Playaround also produced its own internal pairings, releasing the dual demographic combinations of Knight on the Town and Lady in Wading as well as Burning Desire and Jungle Fever. In one of the company’s titles, Gigolo, players enter the seedy yet exciting world of prostitution. Players assume the role of a female prostitute, and wander from house to house, running from the police, as they look for clients; the goal is to find and service a paying client and then to run back to the pimp’s house to cut the earnings. In Cathouse Blues, the player’s role is altered, but the gendered dynamics remain the same; the player assumes the role of a male client, and wanders from brothel to brothel looking to get serviced.

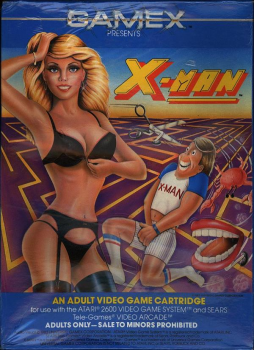

A third company, Universal Gamex released only one title, X-Man, in 1983. The game’s box describes the action: “Coming at you are the ‘Crabs’ with their claws ready to tear your privates apart. Next come the ‘Scissors’ whose sharp blades can cut off your manhood. And last are the ‘Teeth’ who snap with a vise-like grip that will leave more than just marks! Get the picture?” The goal of this maze game is to reach the screen’s center, where a “’Sexy Blond’ with a body that doesn’t quit is waiting behind the door to satisfy your every fantasy.”

In a May 2006 Computerworld news column on new disc formats, Lucas Mearian suggests “Just as in the 1980s, when the Betamax and VHS video formats were battling it out for supremacy, the pornography industry will likely play a big role in determining which of the two blue-laser formats—Blu-ray Disc and HD-DVD—will be the winner in the battle to replace DVDs for high-definition content… The pornography industry, which generates an estimated US$57 billion in annual revenue worldwide, has always been a fast leader when it comes to the use of new technology… .”i While the case for the porn industry is undoubtedly overstated in such reports (VHS succeeded as a less costly open format, while Betamax was proprietary, owned by Sony; and in the current format wars, vertically integrated entertainment companies, movie studios, and hardware manufacturers are also major players), the analysis, picked up by Reuters, rightly acknowledges the historical foundation of such claims. In the 1980s, the advent of home video revolutionized the adult film industry, which was quick to respond to changes in the media landscape and capitalized on the move to a more intimate viewing format (it had everything to gain as titles began to circulate into the home market). And it is not surprising that adult entertainment companies began to explore gaming in the early years of the decade, as video game consoles had been installed in nearly 15 million American homes and formed part of a $7-billion-a-year gaming industry. In a 1982 report, the market research organization International Resource Development, estimated that home video games would prove a significant threat to Hollywood box office receipts by 1984.ii

Companies such as Mystique and Playaround seemed to acknowledge the interpretive powers of their adult audience. Such a gesture may have been necessary, for the gaming graphics themselves do not invoke transparency; falling far from the codes of classic realism, the games seem to consciously address hypermediacy as they attempt to recoup the only pleasure possible—one of a glaring self-reflexivity that borders on the absurd. Consider their awkward repurposing and perhaps defamiliarization of the console (used in a solitary masturbatory fantasy) and the pixel, and the pointed example supplied by the threat of castration writ large in the Gamex title X-Man. The jarring disjuncture between realistic box art and rudimentary game art was an all-too common experience in the world of 8-bit gaming. How many kids were disappointed once they got beyond the package of Raiders of the Lost Ark or E.T. to experience the barely recognizable icons of two-dimensional game play?

Despite the warranted concern about the conflicted gender politics of most of the adult titles produced during the 1980s, the early years of the decade do illustrate the potential for gaming prior to licensing restraint, and the liberatory possibilities of such a gesture—taking gaming out of the hands of children and understanding play as a necessary component of adulthood (though still something that can be colonized by the culture industries). As a distinct axis of convergence, adult and childhood fantasies could be ritualistically played out on the same system. The adult entertainment industry responded to a decided shift in the media landscape at a time when gaming was a more open playing field. In more recent years, adult content has been relegated to the producers of more centralized industries, as hardware developers have taken back control of their platforms, perhaps acknowledging the vitality of adult players looking for both sex and violence, and sex has become one trademark offering of diversified content developers who produce titles across ratings categories. In the early eighties, the concept of the supersystem was just gaining momentum. In the face of several nascent transmedia enterprises, a new paradigm of intertextual possibilities was emerging, though it had hardly been perfected. As a case in point, despite the box office success of E.T., the Atari cartridge of the same title was a commercial and critical failure—though perhaps the result of the company’s own mismanagement of the property. My goal in revisiting the erotic games of yesteryear is to open up a dialogue about the potential of an incoherent supersystem, of a console in crisis, in search of narrative synthesis. The plot lines of most of the adult titles created for the Atari 2600 follow a simple trajectory; the player must overcome duress to achieve momentary sexual satisfaction, only to return to a state of duress. This process is acutely aligned with the Freudian master plot, the game of “fort/da”, which seems to bind the game play of both age groups and can also be applied to the meta-narrative that describes the rise and fall of competing systems.iii Loss is a powerful phenomenon that may lurk beneath even the most whimsical of pursuits. And we must be suspicious of the moments where its possibility is sealed over, where the hack or infringement is rendered obsolete. It is in this latter state, when the supersystem has successfully coalesced, that narrative openness has been delimited, and loss has given way to economic security and ideological fixity. Atari’s origin story is often written as a series of annual reports, tracing the company’s financial demise—a tale of changing ownership and managerial missteps; but the more interesting tale is found in the deceptively simple narratives that played out on its consoles in family rooms across the nation.

Image Credits

Custer’s Last Stand box art: atariage.com

X-Man box art: atariage.com

Screen shots courtesy of the author.

Notes

i. Computer World article

ii.Aljean Harmetz, “Home video games nearing profitability of the film business,” The New York Times (Late Edition, East Coast) October 4, 1982, A.1

iii. Marsha Kinder, Playing with Power in Movies, Television, and Video Games (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1991), 20.

Please feel free to comment.

Wow, the pictures are great! Very entertaining article … although I think they completely missed their market with “X-Man.” That is a game that would do great in certain lesbian circles!

I was intrigued by the comment that the gaming system companies learned from this experience with Atari so that they locked down their consoles from playing unofficial, third-party games. It got me thinking about how we’ve got Tapscott and Williams, in Wikinomics, telling us that for companies to survive in the 21st century they are going to have move towards an open model that takes advantage of resources from outside the company. I’m wondering what is the delicate line between learning, growing, and improving from capitalist competition or from wikinomics type collaboration? With the gaming companies constantly trying to develop the next best way to make more robust, faster, etc., gaming systems and more complex games…might we see this model starting to play out there? And how will “alternative” audiences and markets like pornography and education factor in?

Thanks for ideas to think about!!

Pingback: Nerdcore — Atari 2600 sex’d

Pingback: +PositiveCurfew » Blog Archive » 8-bit porn

I like it!

it would be really super if the game makers mad a porn game and lots of them for the ps2&ps3&all of that

Great flash from the past. You should do a write up of some of the adult titles they made for other early systems like the Commodore 64.

Pingback: Harry, der Fensterputzer | Superlevel

How about the recent hot water that Rock Star Games got into over the hidden sexual content (Hot Coffee) inside of there most popular title, GTA?! Makes you wonder how many games might have super hidden content.

Pingback: Episódio 12 - The Internet is 4 PORN! « WeRgeeks.net

Pingback: We’re Riding On The Internet

Pingback: It’s Time for 8-Bit Porn | SlashUp

I’ve found a modern 8-Bit Porn Game — check this out:

http://www.pornbb.org/8-bit-er.....75307.html

Fack great!!