Born into Failure: Disrupting Narratives of the WNBA Through Remembrance of the abl

Dafna Kaufman / University of North carolina at Chapel Hill

During the 1990s, David Stern, the all-powerful commissioner of the NBA, led the American basketball sphere to global prominence. Stern used the 1996 Olympic Games and the hype around the women’s basketball team as a test-marketing assessment for a potential women’s basketball league. Capitalizing on the correct mix of cultural popularity and commercial backing, Stern used NBA funds and connections to help launch the WNBA. By 1997, the NBA-sponsored WNBA began its first season.

However, Stern and the WNBA were not the first to enter the women’s basketball scene. The American Basketball League (ABL), another women’s league, began months before the WNBA. Many saw the ABL as a misconceived fantasy in competition with the monolith that would be the WNBA—even when the WNBA was simply an idea in Stern’s head. As we celebrate 25 seasons of WNBA basketball, I ask why the ABL was born into failure? Why, before the WNBA even existed, did the media and many players see the ABL as failure-bound? In this commentary, I suggest that exploring the ABL and its accomplishments and its failures can aid in a recontextualization of the current state of women’s professional basketball.

Exploring failure can offer distinct rewards and forms of knowledge production. In The Queer Art of Failure, Jack Halberstam defines success as a function of “heteronormative, capitalist society.”[1] Halberstam asserts that while society may think otherwise, “failing, losing, forgetting…unbecoming…may in fact offer more creative” ways to experience life.[2] Not only can failure create the conditions of possibility for new and different ways of being in the world, but it also permits an escape from the disciplining norms that control our behavior. Following Halberstam, how can thinking through the ABL’s history and “failure” unsettle assumed knowledge regarding women’s basketball in the present day? And most significantly, does the “winner” represent the best option for female athletes? Revitalized narratives of the ABL can perhaps offer a model of rupture for the current state of women’s professional basketball.

Even in texts written before the ABL’s demise, writers presented the ABL as a pipe dream clashing against the powerhouse of the NBA-sponsored WNBA. The ABL, a women’s basketball league organized by a group of independent owners, scheduled its games for fall and winter (the traditional basketball season) and paid players an average of $80,000 per year including medical insurance.[3] The ABL celebrated its independence as a league solely focused on women’s basketball. Their slogan—“It’s a Whole New Ballgame”—touted their autonomy. While the ABL reveled in their self-sufficiency, the WNBA played their games in the summer, so as not to coincide with the NBA season, and to maximize their TV exposure by taking advantage of the lack of men’s sports occurring over the summer. The WNBA also paid its athletes much less than the ABL ($30,000 to $35,000 per year) and provided fewer benefits. Yet, with NBA patronage, the WNBA obtained “marketing, sponsorship and broadcasting of which the ABL could only dream.”[4] The WNBA managed powerful corporate sponsors allowing for a much more polished, commodified presentation than their ABL competitors.

While in its first year, the ABL seemed to be a great success, a cloud always existed above the league’s head. Haunted by the Women’s Basketball League (WBL) and its attempts to present women’s basketball as approachable and indisputably heterosexual, the ABL “would be a ‘player’s league,’” that made no compromises when it came to image.”[5] As Jennifer Azzi, one of the first Women’s Olympic players to sign with the ABL, stated, “[w]e don’t want to be a sideshow to the men.”[6] Yet, even with such promise and potential, the ABL could not keep up with the WNBA’s media power. Sylvia Crawley, an ABL player, argued, “[w]e really got little respect …When I told people I played for the ABL, they would tell me just to work hard and one day I could play in the WNBA. They didn’t realize the ABL had more depth and higher salaries. That was the power of the media.”[7] As the WNBA capitalized on their network connections and sponsorships, the ABL lost TV contracts and could not sign major sponsorship deals, which lead to the league ending and filing for bankruptcy during the 1998-1999 season.[8]

As the ABL faltered, press surrounding the league’s demise constructed a reality where the ABL could never have endured. Richard Sandomir, a New York Times reporter, wrote “[t]he failure of the American Basketball League was foretold almost from the beginning.”[9] In a piece from the following year, Lena Williams states, “[t]he commonly accepted account of the A.B.L.’s collapse is that the league…ran into the buzzsaw of the WNBA…The A.B.L., by this account, didn’t have a chance.[10] Beth Morgan, an ABL player, echoes these thoughts in a piece for a local newspaper. Morgan asserts, “(The ABL) lasted almost three years…People never gave them that chance. They came from nothing and had the best players in the country.”[11] Seen by the media as the WNBA’s inferior sister, the ABL was marked by failure from its beginning.

Even though the ABL could not maintain financial security, the league created new conditions of possibility for female professional athletes. When the ABL ended “players and coaches mourned the passing of a league that put women’s basketball front and center.”[12] The ABL did not produce heteronormative, capitalist visions of success, but it succeeded in offering a different vision of women’s professional sports. While the media presented the ABL as failed from its nascence, that very failure became reality through the actions of (i) the NBA, who wanted sole custody of the women’s professional basketball sphere and (ii) media sponsors who wanted the promised success of a women’s league owned and governed by men. Studying the world the ABL created and left behind reveals practices that treated players with dignity, paid for their labor, and celebrated their own forms of athleticism. Through a recuperation of the ABL–its history, its practices, and its failures—we can see more vividly the shortcomings and patriarchal structuring of the “more successful” WNBA.

In order to fully understand the WNBA’s present-day secondary status in American professional basketball, it is worth considering structural and societal factors which have allowed for the rather poor treatment of WNBA athletes. The WNBA, created with a shorter season than the men’s league, became a part-time job for many players, rather than an all-year career. Due to this shorter summer season, many professional women’s basketball players travel abroad to play overseas after the WNBA season ends. This dual career not only complicates the athlete’s lives, but also does not allow them to rest between seasons producing many routinely hobbled and exhausted players.

While this international labor issue still haunts the WNBA, the most obvious area in which the NBA preserves the WNBA’s secondary status manifests through pay inequity. While NBA players receive some of the highest paychecks in the sporting world, WNBA players receive a fraction of such compensation. For instance, during the 2019-2020 season, NBA players earned on average $7.7 million, while WNBA contracts for the same year averaged around $116,000.[13] This lower pay is often justified through television ratings which normalizes “women’s secondary status within…mainstream sports media.”[14] Yet, the pay inequity between the NBA and WNBA goes beyond television ratings. The WNBA, following the NBA, sustains and maintains ideals of capitalism, commodifying and objectifying the players for profit.

Therefore, until the WNBA creates profit at the same rate as the NBA, WNBA players are not deemed worthy of a better organized season, safer labor practices, significant compensation, or media representation. This logic remains flawed because until the NBA and media outlets appreciate the WNBA as the NBA’s equal, there is no way for the WNBA to change. After 25 years, the WNBA cannot bring in the same sorts of profits as the NBA because the league was designed to be the second-tier of professional basketball in America. As an NBA- produced entity, the WNBA is consistently compared to its male predecessor and found deficient. A circular logic of patriarchy and commerce maintains the power of the NBA over the popularly understood insignificant, second-class citizens of the WNBA.

While the ABL may be forgotten or deemed failed due to its inability to produce certain economic value, the league’s history and “failure” is worth remembering, affirming, and presenting now. The ABL was not perfect, nor is the WNBA, but perhaps by centering the ABL as a prominent piece of women’s basketball history, we can generate a different kind of thinking that pays productive attention to this historical league that attempted to center its powerful female players.

Image Credits:

- The 1996 U.S. Women’s Basketball team celebrates their Olympic victory.

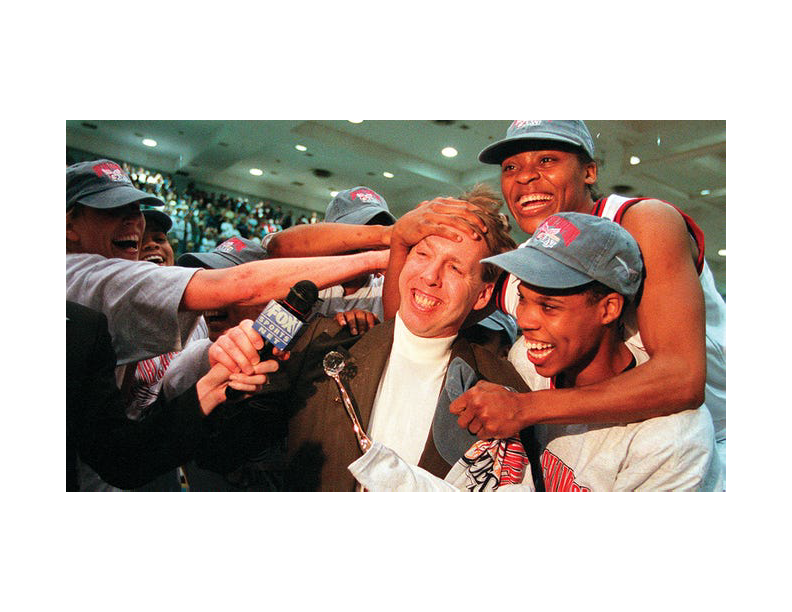

- One of the most successful ABL teams, the Columbus Quest, won both championships held by the league.

- Dawn Staley, current coach of the University of South Carolina’s Women’s Basketball team, showing her physical prowess as a member of the ABL team, the Richmond Rage.

- Jack Halberstam, The Queer Art of Failure, (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2011): 2. [↩]

- Halberstam, Queer Art, 2-3. [↩]

- Pamela Grundy and Susan Shackelford, Shattering the Glass: The Remarkable History of Women’s Basketball, (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2005), 225. [↩]

- Grundy and Shackelford, Shattering, 226. [↩]

- Sara Corbett. Venus to the Hoop: A Gold-Medal Year in Women’s Basketball, (New York: Doubleday Publishing, 1997), 49. [↩]

- Grundy and Shackelford, Shattering, 225. [↩]

- Grundy and Shackelford, Shattering, 228-229. [↩]

- Grundy and Shackelford, Shattering, 229. [↩]

- Richard Sandomir, “Too Few Dollars, No Real Exposure,” New York Times, Dec. 23, 1998. [↩]

- Lena Williams, “Former Team Official Recounts the A.B.L.’s Dizzying Descent,” New York Times, Apr. 02, 1999. [↩]

- Rick Woelfel, “ABL end surprised Morgan,” South Bend Tribune, Jan. 05, 1999. [↩]

- Grundy and Shackelford, Shattering, 225. [↩]

- Christopher Garcia, ““Betting on Women”: A Feminist Political Economic Critique of Ideological Sports Narratives Surrounding the WNBA,” The Political Economy of Communication 8.1 (2020): 35. [↩]

- Garcia, ““Betting,” 36. [↩]

nice post