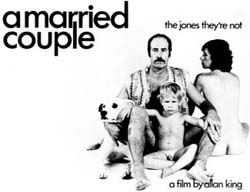

A Married Couple: Reality TV’s progenitor turns 40

Zoë Druick / Simon Fraser University

Allan King’s “actuality drama” about the life of an ordinary couple, A Married Couple, is 40. In the simplest terms, A Married Couple observes the relationship of a white, middle class couple in mid-life (he is 40, she is 30) with a young family. They wrestle with their intimacy and simultaneously with social gender roles in the nuclear family. Billy works in advertising; Antoinette works in the home. In place of plot, the film offers a compelling series of set pieces in which repetitious emotional scripts are enacted. Although the couple seems unhappy with the marriage most of the time, and many of the scenes are of fighting, they also seem ill equipped to resolve their difficulties. Or, put differently, the viewer is invited to see that awareness and even insight about problems doesn’t necessarily lead to change.

70 hours of footage shot over ten weeks was edited down to just over 96 minutes. Even those 70 hours represent but a fragment of the eight years Billy and Antoinette had spent together by the time the film was shot in the summer of 1968. Rather than see the film as a transparent window onto the Edwards’ relationship, King astutely labelled the film more generically as about a particular kind of relationship—marriage—and frankly acknowledged the effect of both camera and editor on the everyday performances filmed. As King put it, “One has to be very, very clear. Billy and Antoinette in the film are not Billy and Antoinette Edwards, the couple who exist and live at 323 Rushton Road. They are characters, images on celluloid in a film drama. To say that they are in any other sense true, other than being true to our experience of the world and people we have known and ourselves, is philosophical nonsense. There is no way ninety minutes in a film of Billy and Antoinette can be the same as the actual real life of Billy and Antoinette.”1

A Married Couple had an impact on the growing area of non-fiction drama and was cited as an inspiration by Craig Gilbert, producer of An American Family, itself often credited with being an inspiration for reality TV.2 Today, in an era characterized by the dominance of reality-based programming, the importance of the film as a pioneer in mobilizing observational media in personal spaces is inarguable. Yet, as time passes, the originality and insight of A Married Couple comes into even greater focus.

Although the idea of recording and exposing everyday life is arguably a foundational part of the documentary impulse, a corrective to the artificial fantasy of mainstream fiction perhaps, King’s version was entirely of its moment. In the late 1960s, traditional domestic and cinematic forms were both, in different ways, being brought under scrutiny. King’s concept of using observational documentary to explore the changing experience of the nuclear family was extremely timely. But its interactive form is perhaps its greatest innovation. The film is connected at once to practices of action therapy and avant-garde theatre.

Psychodrama’s emphasis on group interaction and “relationship-based psychotherapy” became a significant influence on the post-war self-help movement.3 According to this theory, acting out became a way of bringing the unconscious to the surface. At the same time as the theatrical was becoming a popular cultural idiom, practitioners of experimental and avant-garde theatre were questioning the conventions of the stage. The sentiment of avant-garde theatre of this period can be encapsulated by the following question: “How do we know we are watching theatre and not simply observing the world around us?” For many artists experimenting with theatrical practice, the answer was to place emphasis on the frame itself as the technology that created spectator and theatrical event alike. Groups such as the Living Theatre brought these questions to the fore, attempting to bring about revolutions in perception, which could be brought to bear outside of the theatrical experience. If perceptual patterns reinforced social norms—indeed were social norms—then interrupting perception at the artistic level could have an effect on other social regulations. The avant-garde’s ideas about the blurring of lines between art and life influenced the 1960s counterculture’s even looser ideas about be-ins and happenings.

Although not usually thought about in this context, observational cinema emerged in the same period and shared some features with post-war avant-garde theatrical theory and therapeutic discourse alike. Its lightweight hand-held cameras and tape-recorders were developed in order to allow for the capture of uncontrolled, spontaneous situations. Theatre could now take place anywhere. The sense of “being there” was an essential part of what lent this kind of filmmaking its sense of authenticity. Not only was the emphasis on authentic performance, but, as in the theatrical avant-garde, the observational cinema frame is clearly accentuated.

There was, on the part of some observational filmmakers, and likely film subjects as well, a direct engagement with the discourses of therapy. Ever since anthropologist-filmmaker Jean Rouch and sociologist Edgar Morin had encouraged people to talk in the presence of the camera in Chronique d’une été (1961), observational filmmakers had been open to the role of camera as provocateur. What was being captured on film were precisely the kinds of heightened performances the camera could elicit. While American observational filmmaking tended to emphasize public performance, another strain, including King’s, focussed on the private realm and the need for intimate communication and personal self-reflection. For this strand of filmmaking truth has a psychoanalytic resonance “because of the way the camera brings to the surface what is normally hidden or repressed in the subject’s social personality.”4 This psychological or therapeutic understanding was closely related to the relationship of the filmmaker to film subject. In a sense both were equally exposed and the interaction had to be an ethical one predicated on mutual trust.

Reality-based media are now central in mainstream culture, of course. Their production and analysis would certainly be enriched by attention to historical predecessors such as A Married Couple. For instance, today, with a preponderance of reality-based programming on television, aspects of the idea of everyday performance have become commonplace. The fact of ordinary people performing for the camera has become an increasingly common aspect of both everyday amateur media usage and large-scale entertainment. Questions of authenticity are routinely invoked. Yet the social analysis mobilized by 1960s practitioners and theorists of observation, performance and theatricality is often lost. Frequently, truth is conflated with the technological means of reproduction. The avant-garde idea of using media experimentation to challenge social norms and frameworks of perception is lost. Gone too are ideas of the heightening of experience in front of a camera to enhance participant insight. If anything, today’s reality television naturalizes rather than questions the Social Darwinism of competitive capitalism and the governmentalized social context of neoliberalism that it exposes.5

The proliferation of reality-based TV today makes a re-examination of A Married Couple all the more astonishing. How might reality TV question the social order rather than reproducing it? How might film and videomakers work with their subjects to craft interactive hybrids such as the “actuality drama”? King, who died last year, said: “I thought it would be fascinating and illuminating to stay with the couple and observe… Most particularly, I was concerned with a marriage in crisis and wanted to observe the kinds of ways in which a couple misperceive each other and carry into the relationship anxieties, childhood patterns, all the things that make up one’s own personality and character. But these inevitably distort the other person and make true intimacy or true connection difficult. … It puzzled me that people always seemed to get less from marriage than they wanted.”6

Four decades on, A Married Couple still shows how reality-based media might operate to propose questions and spark engagement from participants and viewers alike.

Image Credits:

1. A Married Couple

2. A Marriage in crisis

3. Allan King

Please feel free to comment.

- Alan Rosenthal, “A Married Couple,” in Alan Rosenthal, ed. The New Documentary in Action: A Casebook in Film Making (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1971), 32. [↩]

- Jeffrey Ruoff, An American Family (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2002), 12.

[↩] - Paul Wilkins, Psychodrama (London: Sage, 1999), 12. [↩]

- Michael Chanan, The Politics of Documentary (London: BFI, 2007), 215. [↩]

- Mark Andrejevic, Reality TV: The Work of Being Watched (New York: Rowan and Littlefield, 2004); Laurie Ouellette and James Hay, Better Living Through Reality TV. Oxford: Blackwell, 2008. [↩]

- Alan Rosenthal, “A Married Couple,” in Alan Rosenthal, ed. The New Documentary in Action: A Casebook in Film Making (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1971), 23.

[↩]

Zoe,

I really appreciate your bringing “A Married Couple” back into focus, as I had forgotten where it stood chronologically in relation to “An American Family” and other reality TV progenitors. I also like that you highlight King’s differentiation between the on-camera and “real-life” couple, which seems to be an extremely important distinction.

On the other hand, I guess my question remains whether this documentary, and others that followed it, have an inherent value beyond the spectacle of viewing? My impression of watching this film for the first time did affect my view of relationships, particularly the patterns that couples get into when fighting. Is there a way that we can repatriate this positive (and perhaps therapeutic) aspect of observational works?

It strikes me that it is too easy to generalise when it comes to this sort of topic as no two people are the same and it is a case of compatabilty.

I believe that there are too many reality shows and if you have seen one you have seen them all. Ussually families depicted in these reality shows are very different to the average person take for example Sharon and Ozzy Osborne.

As a “very young” account executive I worked with Billy Edwards at McLaren Advertising in Toronto in the 1960’s and dined at his house several times. The film was a very realistic examination of the marriage dynamic between Billy and Antoinette. The film has often been the subject for my examination of the absurdity of censorship in movies. As I recall, and the details might be a little sketchy, the Ontario Film Censor, Mr. Silverthorne I believe, refused to allow the film a certificate for exhibition in Ontario because the word “fuck” was used too many times by the couple. When Allan King and Silverthorne met to discuss this issue, the number of times the word “fuck” was used seemed to be the issue, not the word itself. When King asked for advice as to which uses of the word needed to be removed, Silverthorne apparently responded that he did not care which, as long as the number was substantially reduced. … At least that is how I remember the story; perhaps it is described more accurately in Alan Rosenthal’s book on the film.