“Rabid”, “obsessed”, and “frenzied”: Understanding Twilight Fangirls and the Gendered Politics of Fandom

Melissa Click / University of Missouri

Twilight fans at the Los Angeles movie premiere, November 2008

I have kept an AP story from my local newspaper in my office since July 2008. It describes the addition of 100 words to the Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary. The story, which finds humor in words like “pescatarian,” and “mondegreen,” drew me in for a laugh, but I stopped when I scanned the text box of selected terms and found “fanboy.” Merriam-Webster editor Peter Sokolowski justifies the addition of the words by suggesting that it is only when words are found to be “used without explanation, translation or gloss” that they become legitimate parts of the American vocabulary. I wondered why “fanboy” fit that category and “fangirl” did not. I keep the article not because I am having trouble getting past Merriam-Webster’s omission, but because I believe the inclusion of fanboy (and exclusion of fangirl) resonates with my work as a feminist media scholar who studies fans.

The feminist critique of cultural studies’ treatment of girls, and the media they enjoy, developed in part with McRobbie and Garber’s critique of subculture scholarship, which they suggest positioned boys as resistive to mainstream culture and rarely discussed girls at all. Arguing against the assumption that the omission of girls in these accounts indicates that girls are uncritical consumers of mainstream culture, McRobbie and Garber insist that “Girls negotiate a different leisure space and different personal spaces from those inhabited by boys. These in turn offer them different possibilities for ‘resistance’ …”1. Despite three decades of influential feminist research, scholars continue to fight the persistent cultural assumption that male-targeted texts are authentic and interesting, while female-targeted texts are schlocky and mindless—and further that men and boys are active users of media while girls are passive consumers. For instance, Driscoll argues that feminist cultural studies scholars must address the “tendency to represent and discuss girls as conformist rather than resistant or at least to study them almost exclusively with reference to that division.”2 Putting Merriam-Webster, McRobbie and Garber, and Driscoll together: fanboys have greater visibility in popular culture because their interests and activities have become an unspoken standard. Fangirls’ interests and strategies, which do not register when positioned against fanboys’, are ignored—or worse, ridiculed.

Nowhere is this more prevalent than in the current treatment of the Twilight Saga, the wildly popular franchise built upon Stephenie Meyer’s Young Adult book series. The series, based on the romantic relationship between human Bella Swan and vampire Edward Cullen, includes Twilight (2005), New Moon (2006), Eclipse (2007), and Breaking Dawn (2008). Together, the four books have sold more than 85 million copies worldwide, been translated into 37 languages3, and spent 143 weeks on the New York Times best-seller list.4 The Atlantic suggests that the “four books are contenders for the most popular teen-girl novels of all time.”5

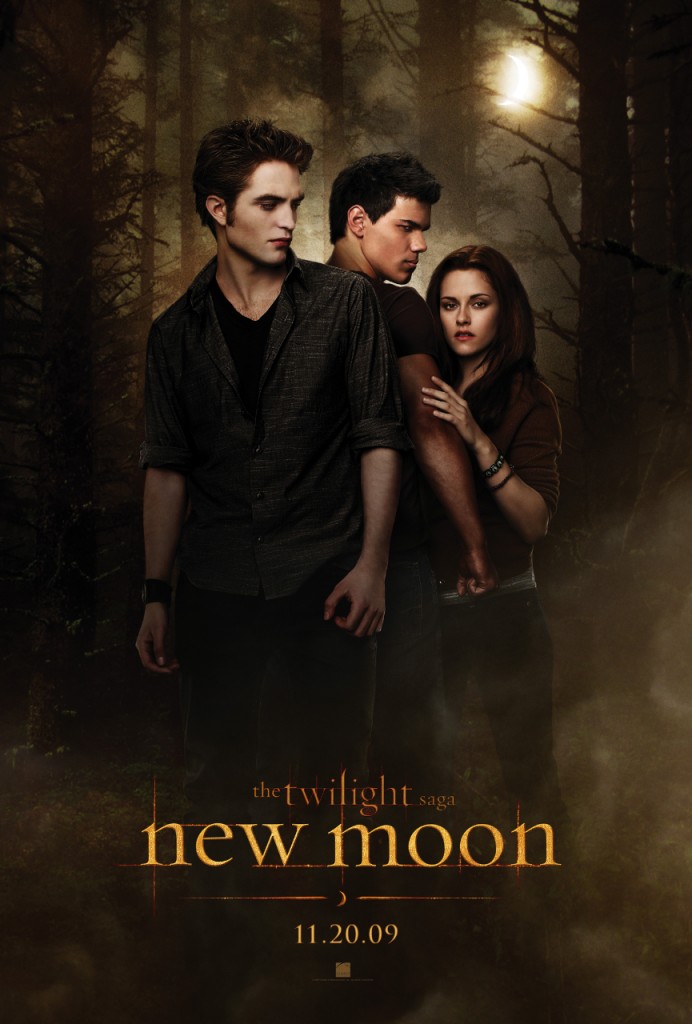

Promotional poster for 2009’s New Moon

In November 2008, Summit Entertainment released the film version of Twilight, which earned $35 million in its opening day, nearly recouping its budget. Twilight’s first weekend sales brought $70 million and set a record for a female director.6 The New Statesman proclaimed that the film was “by far the most financially successful vampire flick of all time.”7 When the franchise’s second film, New Moon, opened last month, its midnight ticket sales ($26.3 million) broke the record set by Harry Potter and the Half-blood Prince in July 2009.8 In its first weekend, New Moon earned $140.7 million in North America, and an additional $118.1 million overseas. 9 New Moon’s opening was the third-biggest on record, displacing Pirates of the Caribbean: Dead Man’s Chest.

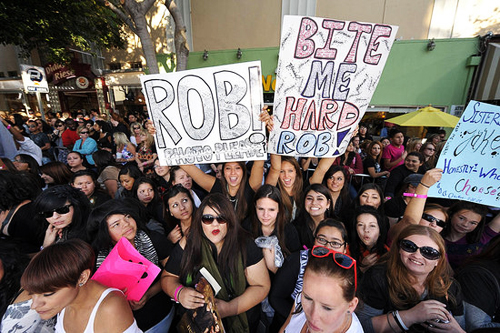

Robert Pattinson greets Twilight fans

Though the popularity of Meyer’s series is noteworthy on its own, the public reaction to Twilight has been striking: the popular press seems bewildered by the success achieved by a series targeted to female fans. For example, after Twilight’s big opening in November 2008, Maclean’s declared, “Twilight confirms there’s a powerful new demographic in play: the fangirl.”10 Daily Variety proclaimed, “A $70 million opening is generally reserved for family pics or fanboy fare”, and added that “conventional wisdom says female-driven properties aren’t always the safest bet.”11 The brouhaha over New Moon at Comic-Con 2009 sheds some light on why the popular press was perplexed by Twilight’s success: franchises and fan activities are for fanboys. Thus, the girls and women who showed up to support New Moon at Comic-Con “ruined” the fan convention.

While the public confusion over the Twilight Saga’s success is not altogether surprising, these comments position girls and women as unexpected and unwelcome media consumers, and deny the long and rich history of the relationships female fans have had with media texts and personalities.1213 On top of this, the media have belittled the reactions girls and women have had to the Twilight series and the actors who play their favorite characters, frequently using Victorian era gendered words like “fever,” “madness,” “hysteria,” and “obsession” to describe Twilighters and Twi-hards. The New York Times described Twilight fans as “on the rabid side”14 and USA Today portrayed fans as “ravenous” and “in a frenzy.”15 Entertainment Weekly reported that an appearance by Robert Pattinson (the actor who played Edward Cullen in the movie) sent “thousands of besotted girls into fits of red-faced screaming”16; The Boston Globe suggested that fans’ interest in the films’ stars is “enthusiasm bordering on hysteria.”17 These reports of girls and women seemingly out of their minds and out of control disparage female fans’ pleasures and curtail serious explorations of the strong appeal of the series.

“Twi-hards” get excited

This is not to argue that Twilight has no faults—it certainly does, and with colleagues Jennifer Stevens Aubrey and Elizabeth Behm-Morawitz, I am editing a collection of essays (Bitten by Twilight, Peter Lang, 2010) that investigate the Twilight Saga’s messages, fans, and industry impact. But I do wish to stress that media scholars should find Twilight’s success—and the public dismissal of its success—worthy of discussion, if not study. What does Twilight’s success mean for a media industry that favors male-targeted franchises, why is the female-targeted franchise not taken seriously, and why are Twilight fans screaming, blogging and writing fan fiction? Research on other groups of energized female fans offer some clues. Ehrenreich, Hess, and Jacobs, writing about Beatles fans, suggest that girls’ screams give them power: “When the screams [of Beatles fans] drowned out the music, as they invariably did, then it was the fans, and not the band, who were the show.”18 Douglas, writing about Spice Girls fans, offered “When adolescent girls flock to a group, they are telling us plenty about how they experience the transition to womanhood in a society in which boys are still very much on top.”19 Thirty years after McRobbie and Garber’s “Girls and subcultures,” the Twilight Saga presents an opportunity to disrupt the persistent stereotypes about girls, the media they enjoy, and their cultural activities. With at least two films left in the Twilight Saga, there are ample opportunities to enter the public dialogue about fangirls’ preferences and practices. Cultural studies scholars have been fighting these stereotypes for too long to let the gendered mockery of Twilight fans continue unchallenged.

Image Credits:

1. Fans at Los Angeles movie premiere

2. New Moon poster

3. Robert Pattinson greets fans

4. “Twi-hards”

Please feel free to comment.

- McRobbie, A., & Garber, J. (1991). Girls and subcultures. In A. McRobbie, Feminism and youth culture: From Jackie to Just Seventeen (pp. 1-15). (Original work published 1978 [↩]

- Driscoll, C. (2002). Girls: Feminine adolescence in popular culture and cultural theory. New York: Columbia University Press [↩]

- Adams, G., & Akbar, A. (2009, November 24). The world’s richest BLOODY franchise. The Independent (London). Retrieved December 6, 2009 from Lexis Nexis database. [↩]

- Grossman, L. (2008, 5 May). The next J. K. Rowling? Time, 171, 18. Retrieved April 2, 2009 from EBSCOhost database [↩]

- Flanagan, C. (2008, December). What girls want. The Atlantic, 108-116 [↩]

- Johnson, B. D. (2008, 8 December). Twilight zone. Maclean’s, 121, 48, 53-54. Retrieved April 2, 2009 from Academic Search Premier database [↩]

- Jackson, K. (2009, 2 February) There will be blood. New Statesman, 50-51. [↩]

- Fritz, B. (2009, November 21). ‘New Moon’ eclipsing two box-office records. The Los Angeles Times. Retrieved December 2, 2009 from http://www.latimes.com. [↩]

- Barnes, B. (2009, November 23). ‘Twilight’ dawns bright at the box office. The New York Times. Retrieved December 6, 2009 from http://www.nytimes.com. [↩]

- Johnson, B. D. (2008, 8 December). Twilight zone. Maclean’s, 121, 48, 53-54. Retrieved April 2, 2009 from Academic Search Premier database. [↩]

- McClintock, P. (2008, 24 November). Almighty ‘Twilight.’ Daily Variety, p 1+ [↩]

- Douglas, S. (1994). Where the girls are: Growing up female with the mass media. New York: Times Books. [↩]

- Ehrenreich, B., Hess, E., & Jacobs, G. (1992). Beatlemania: A sexually defiant consumer subculture. In L. A. Lewis, (Ed.), The adoring audience: Fan culture and popular media (pp. 84-106). New York, Routledge. [↩]

- Rafferty, T. (2008, November 2). Love and pain and the teenage vampire thing. The New York Times. Retrieved April 2, 2009 from http://nytimes.com. [↩]

- Memmott, C. (2008, July 31). Meyer unfazed as fame dawns. USA Today, 1d. Retrieved April 2, 2009 from EBSCOhost database. [↩]

- Valby, K. (2008, 14 November). Robert Pattinson. Entertainment Weekly, 1020. Retrieved April 2, 2009 from General OneFile database. [↩]

- Gorov, L. (2009, November 15). As Jacob Black in the new ‘Twilight’ film, Taylor Lautner is ready for the attention and the hysteria. The Boston Globe. Retrieved December 6, 2009 from Lexis Nexis database. [↩]

- Ehrenreich, B., Hess, E., & Jacobs, G. (1992). Beatlemania: A sexually defiant consumer subculture. In L. A. Lewis, (Ed.), The adoring audience: Fan culture and popular media (pp. 84-106). New York, Routledge. [↩]

- Douglas, S. J. (1997, August 25/September 1). Girls ‘n’ spice: All things nice? The Nation, 21-24. [↩]

Pingback: Links for the New Year « Celebrity Gossip, Academic Style

Pingback: What if female fans matter? Taking a Bite of Twilight Backlash « Professor, What If…?

Pingback: Why “Vampires Suck” Doesn’t Totally Suck : Ms Magazine Blog

the media loves to find yet more reasons to mock women and teen girls, so when they find something, how ever sexist and plain misoginist to latch onto all the world can do is mock the feebly minded-ness of the fans and the books.

I think in my case it’s because I expect so much *more* of my sex. I remember blokes staring at me blankly when I’d tell them I liked reading classics.. few people (in my admittedly limited experience) are silly enough to dismiss great literature by women like Pride and Prejudice, Frankenstein, To Kill a Mockingbird, etc.

Twilight’s major theme is getting your man and keeping him, while other epics generally have a lot more going on in them (here I indulge in using Lord of the Rings as an example).

This being said, I find Star Wars, Spiderman, and X-Men fanboys to be just as pathetic when they devote too much of their lives to it.

Great column Melissa. Guillermo Del Toro was promoting his new vampire novel on the Colbert Report and directly contrasted it with the “sparkle” vampires. They both joked about the differences between Twilight vampires and the old school vampires. They seemed pretty smug.

http://www.colbertnation.com/t.....o-del-toro

I think a large part of this is not sexism but a new tangent line coming from the “nerd-core” culture. It could be that those circles, which included females, that read Tolkein and watched Star Wars repeatedly were inundated by the grouping together with the (targeted) “tween” demographic of Twilight. Dissention would be expected because of the simple culture clash between the two distinctly different group, not to say there isn’t any overlap.

Pingback: Little Red Riding Hood Makes Twilight Look Like a Masterpiece. : Ms Magazine Blog

Pingback: Little Red Riding is no Twilight « Seduced by Twilight

Pingback: What if instead of trying to jump on the Twilight bandwagon, Little Red Riding Hood opted for a feminst re-envisioning of the tale? « Professor, What If…?

I’m really interested in hearing more about the legitimacy of “things girls like” vs. “things boys like”. I suspect that forms of media like comic books and video games don’t receive the stamp of legitimacy because of their “childishness”, while things like romance novels only miss the mark because they are things females like. Is trash media for men trashy because it’s childish, rather than because of their maleness? I’d argue yes.

On the other hand, I can’t stand Twilight. I only read it for science.

Pingback: Breaking Dawn OR How A Smart, Independent, Educated Woman Learned to Love Twilight « girls like giants

So they took out their fire arms, and the suspect was shot in the foot.

” This is directly from Lewis Carroll’s “Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland. But the one prize they still seek is the one most valuable to Voldemort: Harry Potter.

Pingback: Session #2 – summary – Carla Salvatore

Thanks, Julio Toomer for flowjournal.org

Pingback: Blog Post #6 for INFO 200: Issues your information community may face on an international scale – Book Nest