Bundling Merch into the Comfort Economy

Alyx Vesey / University of Alabama

This is the third installment of a three-part series entitled “Making Music in a Crisis.” The first installment in the series can be found here, and the second can be found here.

Last May, I got tired of staring into the void. As remote meetings restructured my daily routine during the first few months of the pandemic, I fixated on the small details inside the closed frames of domestic life that colleagues, friends, and family composed for Zoom—bookshelves, curtains, plants, heirlooms, posters, green screens, ring lights. I also noticed that my makeshift dining room office was the only space in my home without wall art.

As a music fan with a house full of concert posters and an inbox full of tour postponements, I knew I wanted my pandemic-inspired interior decorating project to support a working musician. I quickly settled on two screenprints by Colombian artist Lido Pimienta, whose work was showcased in a merchandise roundup NPR Music put together after SXSW 2020’s cancellation. Pimienta originally planned to use the festival to launch her third album, Miss Colombia, a generative meditation on indigenous beauty I was excited to see interpreted onstage.

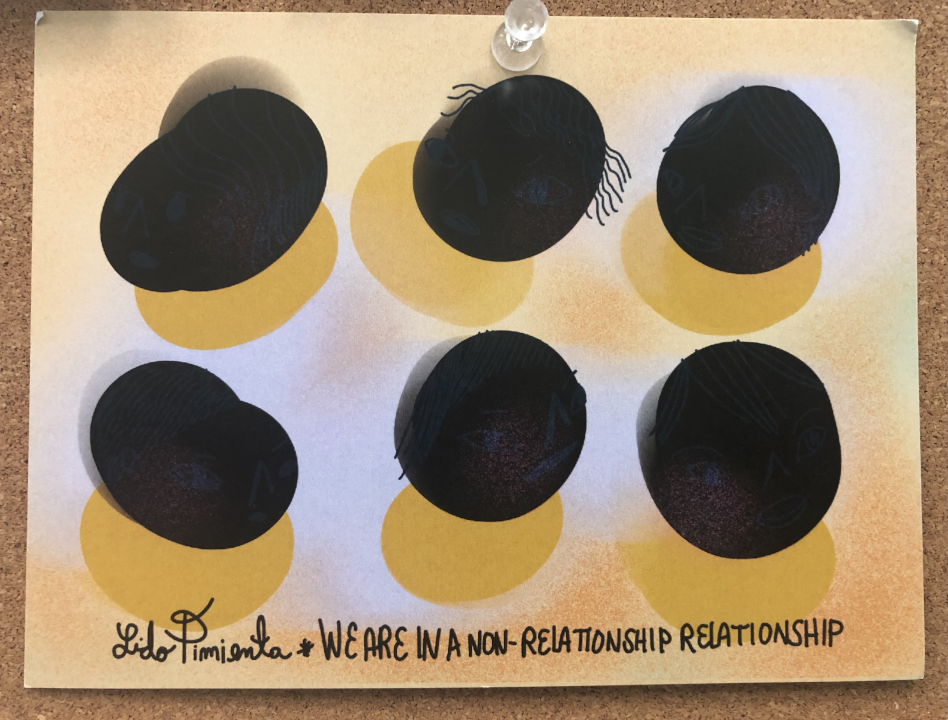

But while I was happy that Pimienta’s orange and turquoise flowerpot face prints brought some much-needed color to a corner of my home, and fortunate enough to be able to afford them, I was struck by what came with them. Pimienta included a thank-you note that proclaimed “[w]e are in a non-relationship relationship.” The phrase comes from her 2017 performance art piece, but it also encapsulates how music merchandise strengthens artists and fans’ parasociality. I don’t know Pimienta, but her art is part of my everyday life. Pimienta’s vivid art and clever packaging also demonstrates merchandise’s importance to musical entrepreneurship and its increased significance during the pandemic, when artists could not promote their work in person.

David Hesmondhalgh posits that entrepreneurship has long been a professional expectation for musicians, particularly in indie scenes, as artists shoulder financial risk or access generational wealth that allows them to invest in their work (1997). Thus, music merchandise not only serves as a way for listeners to wear their fandom. It also functions as a valuable revenue stream for touring musicians, a financial reality that Sleater-Kinney frontwoman Carrie Brownstein acknowledges in her memoir when she recalls how her band “scraped by on merch money” while touring at the beginning of the band’s career in the mid-1990s (2015, 113).

Music merchandise arguably predates phonography. In their work on opera singer Jenny Lind, Steven Waksman and Jennifer Stoever present her popular branded sheet music as evidence of her rise to stardom in the 1840s (2011; 2017). Furthermore, sponsorship has been a part of the concert-going experience since the days of vaudeville. However, music merchandise solidified into an industry during the second half of the twentieth century. Fan clubs included lapel pins in their membership packages during the post-war era. Over the next two decades, venues used music merchandise to appeal to young concertgoers. Two conventions emerged during this time. First, labels like Motown began signing artists to 360 deals that entitled executives to a percentage of profits from “non-musical” goods. Second, clubs installed merch booths so fans could show their support with buttons, posters, and t-shirts. Concert tees gradually became an integral part of music fans’ wardrobes during the 1970s, resulting in merchandise conglomerate Winterland earning over $100 million a year in t-shirt sales by the end of the next decade (Harrington 1989). While hardcore groups like Fugazi rejected music merchandise as emblems of corporate excess during the 1980s, intrepid acts like DEVO and Public Enemy seized upon its artistic and economic merits by supplementing merch staples with specialty items like 3D glasses and bomber jackets that fans could buy through mail order. By the turn of the 21st century, hip-hop artists collapsed merchandise and branded fashion by launching their own clothing lines.

Brownstein also recognizes how bespoke music merchandise became after the 1990s by noting that “really savvy artists” now sell their fans branded “dog sweaters, bibs, keychains, laser pointers, and limited-edition coffee” (113). Her point about savviness speaks to how, as I noted in my previous column, entrepreneurial musicianship has accelerated and intensified during the early 21st century due to streaming’s transformation of the recording industry. Elaborate merchandise is a byproduct of this acceleration. Anyone can sell you a t-shirt. In the Before Times, canny musicians distributed customized wares on tour and in their e-shops and Hello Merch pages as a meaningful form of creative self-expression and product differentiation. Before the pandemic, Mitski nodded to her Japanese heritage with Hilo soup spoons and Dessa highlighted her songwriting talent by selling pencil bags to promote their latest albums.

Bundling, or the practice of folding merchandise into album purchases, has been the subject of much recent attention within the recording industry. It has also problematized the album’s commercial value in an era defined by convergence and disaggregation. What is an album now? Is it a 12” vinyl record? Is it a playlist? Is it an “experience”? Billboard spent most of 2020 trying to uncouple merchandise from its albums and singles charts. In January, it ruled that artists had to sell bundled and unbundled versions of their albums and mark up bundles by at least $3.48—the trade magazine’s minimum qualifying cost for an album. By July, it changed its ruling so that artists were required to disclose bundling as an add-on cost for album purchases. By October, it disallowed artists to claim sales generated by merchandise.

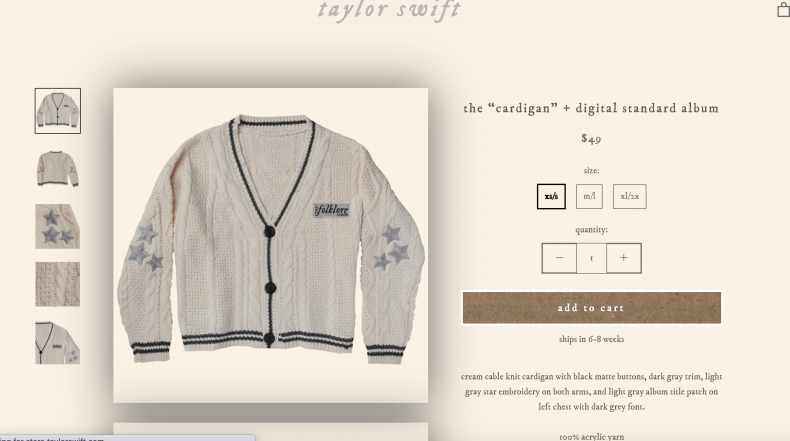

However, cunning institutionalist Taylor Swift outmaneuvered Billboard by releasing 2020’s best-selling album, folklore, as multiple bundles. For many, folklore was a definitive Pandemic Statement Album. It was recorded entirely under quarantine. It represented Swift’s pivot to indie folk maturity that paid off with her third Album of the Year Grammy. It was also her first album unaccompanied by a blockbuster world tour, which allowed the prodigious singer-songwriter to release evermore in time for the winter holidays. Even her merchandise reflected quarantine’s gently informal dress code. To promote the release of folklore’s lead single, “cardigan,” Swift supplied her merch shop with a version of the star-dotted cable-knit sweater she wore in the video for fans willing to spend $50 on winter clothes in July. But by the time her Capital One “Cardigan” ad made it to air in November, the item was sold out long enough for Swift’s closet full of pillowy cream cardigans to register as a joke, possibly on Billboard.

Despite Billboard’s efforts to unbundle merchandise from music in its charts data, music fans hungered for ephemera during the pandemic. Such behavior speaks to the rise of pandemic purchasing as a consumerist response to societal collapse. Atlantic contributor Amanda Mull argued that this phenomenon was a way for people “to help those in need” and remember “our pre-COVID-19 freedoms” by “b[uying] souvenirs of the year we went nowhere.” Some independent record stores have benefitted from this impulse, or at least avoided closure during the pandemic. For example, 2020’s Record Store Day sales outperformed the previous year’s earnings. When asked about it as part of Billboard’s ongoing series about Madison-based record store Strictly Discs, owner Angie Roloff hypothesized that independent record stores benefitted from a “comfort economy” centered on customers buying things “that make them happy at home.” These things vary among music fans, with some people buying merch in place of physical music and others collecting both. How and where they shop varies as well. For example, I bought Pimienta’s art from her store, but I purchased Miss Colombia on Bandcamp.

On March 20, 2020, Web-based music distributor Bandcamp waived its revenue share and donated that day’s sales directly to the artists using the platform. This gesture of corporate benevolence became Bandcamp Fridays, which take place during the first Friday of each month. In many ways, Bandcamp remediates the merch booth. Its artist-centered interface allows musicians to set their own prices and sell merch with their music. Bandcamp Fridays have been more helpful to working musicians than Spotify’s “COVID-19 support” button, a feature that allows users to tip artists but has had minimal impact on musicians’ earnings on the platform.

It has also been interesting to see how musicians use merchandise to respond to the pandemic. For many artists, face masks replaced or enhanced the concert tee as a way to turn fans into billboards. They also serve as a poignant reminder of many artists’ precarious existence and how many musicians we lost to COVID. Face masks will likely still be necessary to wear during this summer’s outdoor festival season as the United States struggles to reach herd immunity due to vaccine hesitancy. Venues have also created branded merchandise as a fundraising tool.

But pandemic-themed and -adjacent music merchandise also informed some of the music artists were promoting. 2020 was a breakout year for indie singer-songwriter Phoebe Bridgers, who released her sophomore album, Punisher, last June. Much like folklore, Punisher’s elliptical anthems about grief and displacement resonated with many people. It also culminated in Bridgers’ Best New Artist Grammy nomination. Like many contemporary artists, Bridgers was shrewd about the album’s branding by using skeletons as the album’s unifying visual motif. She poses in a skeleton costume for the album cover as a nod to the imagery in “Halloween” and “Savior Complex.” She wore skeletal designs for all of her major promotional appearances, including SNL and the Grammys. She also translated Punisher’s goth aesthetic into merchandise by supplying her store with skeleton sweatpants, a branding decision that highlighted the album’s listless tone and capitalized on athleisure’s spiking popularity. Bridgers is scheduled to play a handful of tour dates in the next few months to support an album she recorded in the Before Times but may forever be associated with the pandemic, a year that many of us spent by trying to find solace in accumulation. We’ll be unpacking what we lost for a long time.

Image Credits:

- Lido Pimienta’s Flowerpot Face screenprints. (author’s personal collection)

- Lido Pimienta’s “We Are in a Non-Relationship Relationship” postcard. (author’s personal collection)

- Sleater-Kinney’s Dig Me Out tour t-shirt.

- Winterland Productions’ co-founder Dell Furano.

- Mitski’s “Feed the Cowboy” soup spoon.

- Taylor Swift’s folklore cardigan.

- Taylor Swift’s “Cardigan” ad for Capital One.

- The Bandcamp Fridays banner.

- Phoebe Bridgers’ Punisher Sweatpants. (author’s screengrab from Phoebe Bridgers’ online store)

Brownstein, Carrie. Hunger Makes Me a Modern Girl: A Memoir. New York: Riverhead, 2015.

Harrington, Richard. “The Selling of Rock on the Megabucks Music Circuit.” Washington Post (September 24, 1989): G1, G11.

Hesmondhalgh, David. “Post-Punk’s Attempt to Democratise the Music Industry: The Success and Failure of Rough Trade.” Popular Music 16, no. 3 (1997): 255-274.

Stoever, Jennifer. The Sonic Color Line: Race and the Cultural Politics of Listening. New York, New York University Press, 2016.

Waksman, Steve. “Selling the Nightingale: P.T. Barnum, Jenny Lind, and the Management of the American Crowd.” Arts Marketing: An International Journal 1, no. 2 (2011): 108-120.