The Beatles: Rock Band, A Revolution(?): Myth and Over-determined Discourse

Racquel Gonzales / FLOW Staff

The Beatles: Rock Band, the much anticipated and/or overhyped (depending on your stance) rhythm game by Harmonix was released September 9th, coinciding with the successful release of the band’s digitally remastered music catalogue. However, critical weigh-ins were starting before the game even came out. Since its development was first announced, there were numerous reactions about the game from thoughts of The Beatles “selling out” via video game media, issues of capital fetishizing of the music, to the ongoing condemnation that kids will not play instruments if they play Rock Band and Guitar Hero. Two voices sparked particularly polarizing discussions online: New York Times reviewer Seth Schiesel for his overtly positive game review and the critical blog response by video game scholar Ian Bogost—both receiving mixed commentary from responding posters and bloggers.

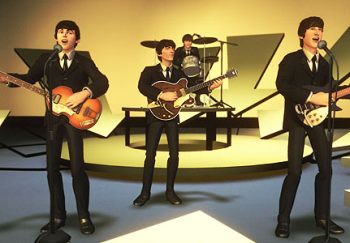

Schiesel lauded the video game for its ability to engage the baby boomer generation through the music of The Beatles and create an “intergenerational cultural resonance” that would allow parents and children to play together.1 This is notable because the industry is making attempts to break out of its connoted definition of a male, teen-centric sphere. He went on to equate the game’s cultural importance and impact, perhaps now infamously, to The Beatles playing on The Ed Sullivan Show in 1964. Furthermore, he declared the game “to be the most important video game yet made” while deriding most games as message-less, meaningless, and without cultural impact and resonance, much to the chagrin of the video game community. In response, Bogost counters that the game is simply baby boomer reminiscence and merely a fancy derivative of the Rock Band franchise. Furthermore, Bogost names The Beatles: Rock Band as “the apotheosis of boomer nostalgia,” packaged for and bought by those who want to reminisce about the greatness of the 1960’s—“the Greatest Generation for that generation children.”2 While he raises issue with The Beatles: Rock Band as marketing nostalgia, he reduces the game to essentially empty 60’s wistfulness while clearly demarcating a line between gamers and baby boomers as mutually exclusive (and arguably Beatles fans and gamers): “Must we appreciate The Beatles? Must we reminisce with the newly aged about their privileged lives as naïve youthful radicals, and then later as greedy yuppie centrists, and then finally as truculent conservative majority? Must we give them their final thrill in the medium we popularized, and which they spent decades not only failing to understand, but also deriding as useless and insolent?”

I (and others) find themselves caught between the polarization of Schiesel and Bogost’s opinions. While I applaud potential intergenerational connection through the game, that alone should not be the basis for Schiesel’s grand hyperbole of the game as the ultimate in video gaming history. Moreover, the assumption that the game and The Beatles are accessible to everyone is problematic, though the game’s promotion has been relying this very idea. And while I can’t deny that 60’s iconography and backdrop is heavy at work within the game, it is not the only cultural memory at work for players or even the creators. The Beatles music (and arguably, music in general) has the capacity to engage both with the band’s temporal cultural moment as well as listeners’ personal memories of engagement, which aren’t always at the prodding of baby boomer parents or desires to wax-poetic about a cool time we wish we’d existed. Rather their opinions help draw attention to how the discourse around the band cannot be separated from the critical discussion of the game itself. Arguably, it overshadows it.

[youtube]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=c-qt5szlQ_U[/youtube]

I can’t help but attribute this situation to the inescapable mythology of The Beatles, a myth reified by the game and its advertising (seen above). The Beatles: Rock Band is truly nostalgic, but for The Beatles themselves more than anything else. This may seem as if I am separating the band from their historical context. But The Beatles have come to be more than just a signifier for the 1960’s; their myth is that of the ultimate band and cultural force—creative geniuses, timeless art, international importance, and universal appeal. This is a myth that took shape in the 1960’s, but has been carried on, renegotiated, and reinstated by subsequent generations. This is not an attempt to erase the historical context, but point out how the group has already been mythologized outside of the 1960’s time-frame, acknowledged by the band members themselves. In a 1980 interview with Playboy, John Lennon reflects, “I don’t mean to belittle The Beatles when I say they weren’t this or they weren’t that. I’m just trying not to overblow their importance as separate from society.” And most recently, Paul McCartney observes of The Beatles: Rock Band game, “I think it reflects where the Beatles are at. We are halfway between reality and mythology.”3. Of course, the myth both hurt and helped The Beatles as a group and in their solo work. Moreover, they are one of the most successful brands in pop culture history as evidenced by their overwhelming Beatlemania fan memorabilia, successful re-releases of their recordings like The Beatles Anthology set and 1, the Cirque de Soleil Show Love, to The Beatles: Rock Band game. This sort of commodification is nothing new for the group who helped merchandise the way music fans connect to a band for better or worse. The Beatles: Rock Band is a product of the mythic associations we have with the band. As well, it will undoubtedly become another way the band’s mythos is delivered and over-determined for a new generation.

[youtube]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hoPWrooRSzY&feature=related[/youtube]

As for the game, it does a truly magnificent job at reiterating the mythic ideology of The Beatles as the perfect band, one that you get to play “with”, not play “as.” Never before heard studio chat is integrated into load screens to give players the feeling they listening into private conversations. Additionally, many critics note how the game rewards players with bonus content about the band in the form of photos, fact blurbs, and archival videos of behind the scenes interactions. Thus, allowing virtual music history and appreciation lessons to take place. Importantly, the end credits name The Beatles for “The Music and Inspiration” as the game does take liberates in maintaining the myth of the band and their music. There is no appearance or acknowledgment The Beatles’ history prior to 1963, so no mention of Stu Sutcliffe, Pete Best, or the band’s humble beginnings. There’s no virtual Eric Clapton on solo in the “While My Guitar Gently Weeps” studio/dreamscape background4 and definitely not any drug use (though some of the more psychedelic dreamscapes may be nods). Those studio dreamscapes are suppose to capture what it was like to record and what it was like to feel the music5. However, they function more as completely idealized musical realities without band disagreements or absences during recordings for particular songs. Really, the game delivers the nostalgic myth of the band: a whitewashed, idyllic history and image of The Beatles, one that perfectly reinstates and honors its already polished cultural image. However, it’s to be expected considering the very active, careful participation by typically exclusive Apple Corps, the surviving Beatles, the deceased Beatles’ wives as well as initial start up prompted by Dhani Harrison.

The Beatles: Rock Band criticism and reception is an advantageous opportunity for discourse analysis. The aforementioned critical polarity as well as divisions of “I love Beatles and…” or “I hate the Beatles, so…” has not or will not prevent meaningful discussion of the game, but can’t seem to break out of the already established ideology of The Beatles. How do we deal with the game while interrogating the myth? Roland Barthes notably grapples with the enormity of myth: “We constantly drift between the object and its demystification, powerless to render its wholeness. For if we penetrate the object, we liberate it but we destroy it; and if we acknowledge its full weight, we respect it, but we restore it to a state which is still mystified.”6. I am guilty of the very trend I discuss in this article, but admittingly, I am also a Beatles fan who waited outside on September 9th to pick up my reserved copy of the game. So is The Beatles: Rock Band a revolution? Perhaps the better question is how and why the question is posed in the first place.

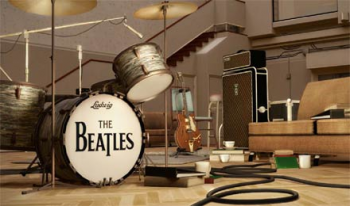

Image Credits:

1. Virtual Abbey Road Studio

2. The Beatles on The Ed Sullivan Show

3. The Virtual Beatles on The Ed Sullivan Show

4. “Here Comes the Sun” studio dreamscape

Please feel free to comment.

- Seth Schiesel. “All Together Now: Play the Game, Mom.” September 6, 2009. http://www.nytimes.com/2009/09/06/arts/television/06schi.html [↩]

- Ian Bogost. “Life Goes On Within You and Without You: On The Beatles: Rock Band. September 7, 2009. http://www.bogost.com/blog/life_goes_on_within_you_and_wi.shtml [↩]

- Original italics. Daniel Radosh. “While My Guitar Gently Beeps.” New York Times. August 11, 2009. http://www.nytimes.com/2009/08/16/magazine/16beatles-t.html?ei=5087&en=68e1babf436ab82d&ex=1265688000&pagewanted=all [↩]

- A photo fact for “While My Guitar Gently Weeps” mentions Clapton’s participation. Likewise, other photo facts reveal Keith Richard and Mick Jagger’s participation in “All You Need is Love” and Billy Preston on “Get Back” and “Don’t Let Me Down.” However, their participation nor the presence of Yoko Ono in later recording sessions are represented in the virtual backgrounds that occur within the game. [↩]

- E3 2009 Microsoft/Xbox 360 Presentation of The Beatles: Rock Band [↩]

- Roland Barthes. Mythologies. Trans. Annette Lavers. Hill and Wang: New York, 1984. http://www.artsci.wustl.edu/~marton/myth.html [↩]

I too was dismayed by Schiesel’s and Bogost’s commentary about TB:RB mostly because both authors participated in the forecasting frenzy, attempting to call first the importance (or over-commercialized nostalgic unimportance) of a much anticipated AAA title. What will be far more interesting to observe and discuss in the coming months is how people are actually responding to and playing TB:RB. While MTV, Harmonix and Apple Corps may have hoped that Beatles/60s nostalgia would sell the game to an “untapped market” of baby boomer gamers, I have yet to see any convincing research (academic, marketing or otherwise) that 1) baby boomers don’t ALREADY play video games and that 2) those who don’t would be compelled to play THIS game. Seems to me (based on available research and years on WOW) plenty of baby boomers play MMORPGs, and if you don’t like music games, TB: RB may be a hard sell. Will the start up costs of all those peripherals deter potential Beatles fans who could drop about $100 less on the remastered CD box set instead?

Video game as documentary is an interesting claim that Schiesel proposes, though not an original one (several sources come to mind, namely J. Raessens, PopComm, 2006, v.4, n.3 and Cindy Porema at shinyspinning.com). Like any documentary or any remediation of an event, it is a carefully crafted construction. Of course the drugs and the band infighting won’t be highlighted. The retail expectations of the game developers and publishers preclude the less sellable aspects of the Beatles history. Watch the promo videos from Harmonix featuring creative director Joshua Randall and you can get a peek at some of the production decisions made that clearly expunged some of the Beatles history. (Best example: The making of the Revolution game video during which the protest aspects of the song were toned down in the animation).

Yes, we can think about TB:RB as hype, branding, commercialization, selling-out, etc. etc., but lest us not forget it is also a music game by one of the (if not THE) most influential groups in pop music history. They fab four wrote an unbelievable amount of music in 10 years and created many of the now cliche riffs, bridges, melodic, harmonic and rhythmic patterns which remain staples of contemporary music. Obviously I’m a fan of the Beatles and the game, and my pleasure playing TB:RB comes from surrounding myself with the music – good music – and imagining that I can play Octopus’s Garden alongside Ringo. Gaming, and perhaps especially music gaming, is so much about the pleasure (and frustrations) of performance. How will this over-determined discourse about TB:RB actually inform the playing pleasure of gamers is a discussion I can’t wait to hear.

Thank you Nina for really great thoughts!

I completely agree with your opinion about the line Bogost demarcates between baby boomers and gamers, which I find quite problematic if not a bit ageist. Personally, I come from a family of gamers from my grandparents (yes, my grandmother plays video games) to our youngest generations, so I found it a quite broad essentialization of gamers. Both Schiesel and Bogost generalize TB: RB as a game and its potential audience to a large degree, which seems to be the theme with the advertising as well.

I am intrigued by this discussion of video games as documentary because “documentary” connotes for many “truth” or “objectivity,” without attention to the active construction as you pointed out. I think the assumption that the public will know the game isn’t really showing the *whole* truth is completely undermined or at the very least muddled by the attention surrounding the game as interactive music history. Of course, the issue of history and History (with that big “H”) and construction is one that is constantly shaped and negotiated, especially in the case of The Beatles. I learned that Let It Be has yet to be released on DVD in part because of the squables and tensions depicted between the four during recording and how unfavorable it reflects upon the band. What I find fascinating is the idea that these are deemed unsellable aspects to The Beatles when I find that many Beatles fans are drawn to these little ruptures and moments of reality that don’t seem to quite fit, moments that juxtapose the ongoing myth of the band itself. The desire to see what’s behind the curtain is not just attached to The Beatles in our culture either. Furthermore, there is an interesting tension between those who want to know and those who don’t want the myth destroyed. I would argue the game makes an even more “perfect” version of the band since Yoko is nowhere to be seen and therefore cannot break up the band as the story goes.

“How will this over-determined discourse about TB:RB actually inform the playing pleasure of gamers is a discussion I can’t wait to hear.” I think you addressed my personal underlying curiosity and what thrusted me to write the article in the first place. How much of the issues around the game and The Beatles affect a player’s relationship with the game? Can and do non-Beatles fans like the game? Furthermore, how and why we play games and music games specifically should be entered into this conversation as well, since there still is an ongoing assumption that X people play Y games for Z reasons. And likewise, this is a discussion I want to hear and be a part.