Television’s Aesthetic of Dead-Ness

by: Dana Polan / New York University

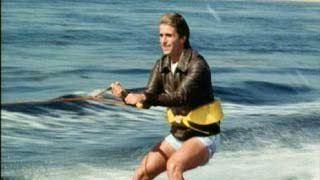

One of the ironies of the notion of “Jumping the Shark” is that it invokes imminent demise through an example that celebrates life. More specifically, the concept, as is well known, refers both to a scene from Happy Days in which the Fonz water-skies up and over dangerous sharks — an act of personal survival (however comically treated) — and to its consequences for the non-survival of the show itself. By winning out over death, the Fonz’s act seals the show’s own fatal spiral toward cancellation.

In fact, many television cases of “Jumping the Shark” appear to involve affirmations of life’s seemingly positive moments only to then lead inevitably into negation of the shows’ very being: you know that Darren and Samantha’s television presence will stop once they have Tabatha or that Maxwell Smart and 99 or Mork and Mindy will soon cease to exist if they decide to marry. The seemingly affirmative step forward seals eventual disappearance. Marry and/or have kids and you risk being cancelled. Only perhaps in the nostalgic netherworld of the rerun channels like TV Land or Nick at Nite or Trio (itself in danger of demise or, at the very least, of being re-purposed away from nostalgic reruns) do the characters gain an after-life, and in that case there can be something ghostly about seeing these figures from an increasingly distant past. (Likewise, the reunion show might seem a re-affirmation of the original world of a series — let’s bring these people back together and give them a new life — but it often has its own ghostliness in its revelation of the ravages of time: for example, the reunion for The Dick Van Dyke Show was filled with wistful flashbacks to characters whose actors had died, and much of the presentness of the show simply reminded one how much the surviving actors had aged.)

The way in which a TV couple’s consummation of love (for example, the case of Max and 99) signs a show’s death warrant is a bit different perhaps from the effect of such consummation in the narrative structure of classical Hollywood romance. The kiss, for instance, that ends the screwball film comedy and seals the destiny of two lovers who have been bickering all through the story is supposed to put all problems to rest and create an eternal present of love: it is true that the film ends, but we are supposed to imagine that the couple’s love will last forever beyond the credits. The film can come to closure because timeless romance has been achieved. In television, in contrast, the fading away of the narrative is often more downbeat or downright abrupt. (For insightful analysis of endings in television, see Jane Feuer’s critical reflection, “Discovering the Art of Television’s Endings” in Flow.)

Indeed, until The Fugitive in 1967 infamously tied up its narrative and enabled Richard Kimble to catch the one-armed man who had killed his wife, it was rare for television shows to even offer any satisfaction through closure. The cancelled shows would simply die, disappearing from one week to the next with their narratives unresolved. Television is often an art of frustration and fatality. (The Fox show Action, about the venality of Hollywood, played with the conventions in order to get back at the network for canceling it. In the last episode — in a season foreshortened by Fox’s abrupt decision to eliminate the series — the lead character dies unexpectedly of a heart attack and the announced time of death is a reference to the moment the producers learned of their project’s cancellation.)

I intend the title of this column to speak of the converse of that aesthetic of liveness that has so centrally been seen as part of the defining quality of the television experience. Just as the idea that television presents liveness is metaphoric, so too the dead-ness I am invoking is not necessarily literal demise (although television is in fact one of the primary sites/sights for the witnessing of fatality, from events around the Kennedy assassination to the Challenger disaster to 9/11 to daily images of warfare). Television finds the converse of live-ness when it takes things we have come deeply to care about away from us and thereby makes us participate in the tragedy of our own fidelities to our popular culture. Yes, television is about presence and plenitude (or about the mythified, constructed appearance of them), but it is also run through with a waning of story, ruptures of continuity, disappearance, a fading away of the images that flit seductively but evanescently before us.

Indeed, as Jeff Sconce notes in Haunted Media: Electronic Presence from Telegraphy to Television, his study of the entwinement of modern image technologies with the spectral and the supernatural, the otherworldly and uncanny quality of television was even reiterated in the cathode-ray period by the way in which the television screen would slowly go empty when turned off, the light gradually diminishing as it hovered between presence and fated absence. (HBO’s lead-in to its shows parodies this by mimicking a television screen turning on to cathode-era static but then enclosing that static within the letters that form the company name as if to say that the older cultural form is now being transcended by new media — “It’s not television, it’s HBO.”)

Certainly, television is about flow, an energetic continuity, a vitality, that goes beyond any one show to create a veritable life-force. HBO, for instance, runs promotional spots that use special effects to merge characters from one show with another as if to say that it’s all part of one big television universe where every experience bleeds into every other and where the spectator is engulfed within a limitless and unending plethora of pleasurable possibility. (However, that great cultural barometer, Mad Magazine, actually beat HBO to the punch, having its Sex and the City parody end with the women deciding there are no good men in Manhattan and going across the Hudson River to hook up with Tony Soprano and his gang. Mad has always mined the knowledge that we live immersed in a seamless popular culture.)

I would contend that discontinuity, interruption, frustration, and a reneging on narrative contract are often as much as plenitude the experience we have of our popular culture. (And, as Allison McCracken suggests in her Flow piece, “Lost”, we need in any case to be suspicious of the sort of plenitude and affirmative fulfillment that today’s culture can offer. Thus, McCracken nicely argues that television’s ongoing recognition of loss and disappearance has been given a veritably reactionary answer in shows that imply Godly redemption and restoration of presence through religiously resonant mythology.)

A medium such as television becomes caught in fraught tension between fulfillment and disappointment. For instance, the example of The Fugitive aside, so much of the viewing experience of classic television was in fact about its frustrating failure to adhere to the goals set out in its narrative premise: the amnesiac Man Called Shenandoah or the guy muttering “Coronet Blue” would never get to recover their memory, a soldier who was Branded and “marked with a coward’s shame” would never get to clear his name, David Vincent would not bring the Invaders to defeat, and so on. The stories that have come and gone on television speak of a vulnerability and dis-continuity, of promises made and broken that are central to the experience of culture.

“Not Italy is offered, but proof that it exists,” wrote Theodor Adorno and Max Horkheimer in “The Culture Industry,” in the context of a discussion of the ways lotteries grip popular consciousness through their simultaneous offer of reward and tough reminder that only a lucky few will in fact win the announced prize. Culture promises, but it also falls short of satisfactory delivery. The planned obsolescence that is so central to the ongoing marketing of goods, including cultural goods, means that capitalism is always promoting something new but also always reiterating that it will always brutally take the old things away.

In this respect, I see my argument as complementary to an essay that came out just as I was beginning to formulate these reflections for Flow: an analysis of the global marketing of the French-Canadian television show Highlander by Shawn Shimpach in the current issue of Cultural Studies (full disclosure: I was an outside member of Shawn’s dissertation committee and am a big supporter of his work). Shimpach begins his essay with a declaration that might seem at first glance the converse of my assertions about the fatality and broken promises of popular culture: “On television,” he says, “immortality seems the rule rather than the exception.” In Shimpach’s analysis, the very subject of Highlander — a man gifted with immortality who travels throughout the globe and across the centuries — is an apt and seductive rendition of an unfettered cosmopolitanism that seeks home and sanctuary everywhere in the world, and it serves thereby as an allegory for ever-expansive flows of capital that themselves seem endlessly renewable and “immortal.”

But capitalism’s liveliness comes often at the expense of ordinary citizen’s livelihood. In the 1950s, anxieties about ways in which the new worlds of suburbia and 9-to-5 white collar labor were turning the worker into an other-directed “organization man” were given metaphoric form in such films as The Incredible Shrinking Man. Today, however, the metaphor turns literal and is lived in one’s very being as the threat of “downsizing” or, in that striking British term, of being made “redundant.” Culture dramatizes this, as much as it promises escapism from it.

Film, television, and media studies may have been doubly hampered by the seductive dominance of French Marxist Louis Althusser’s model of ideology in which the ideological operates to secure reproduction of the means of production by making the worker want to continue to invest in the productive system. On the one hand, although Althusser actually provided little description of the actual mechanics of ideology’s operations, it was easy for fields that dealt with culture’s representations to imagine that ideology was a matter of theme and message — that films or television shows operated ideologically by transmitting affirmative messages about current social configurations. Ideology, in other words, as a sort of civics lesson.

On the other hand, the very emphasis on ideology as the reproduction of production through the securing of a labor force might miss the extent to which, in the flexibilized, casualized mode of production that is late capitalism, it is as important that production not always be reproduced — that, for instance, not every company or subsidiary survive, that workers be vulnerable to downsizing. Television’s ideological functions here might be multiple: the work of ideology might not be to offer civic lessons of rewards for good behavior so much as to remind citizens that the world is too cut-throat for such rewards to be democratically available (hence, the reality shows that make people fight among themselves to serve as survivors or apprentices of the system); it might set up the world not as endless promise or reward but endless cancellation (“you are the weakest link, goodbye”).

And I don’t mean to suggest that television is alone in this. Mass culture in general is necessarily not just a pedagogy about good things, but also the bad. Television is far from the only site in which we are made to play out our own vulnerability to the vagaries of the market and the strictures of work under late capitalism. Thus, in my experience, a theme park like Disneyland can be the offer of fun and sensational thrills but it is also a training in how to live with disappointment — agreeing to wait over long periods of time for meager reward; being disciplined into patterns of line-up obedience and sheepishness; learning that time-management is a frantic business in which immediate gratification may have to be deferred until later in the day; accepting the frequent frustration of not getting, or getting to, everything you were promised; and so on.

In a recent issue of Flow, Derek Kompare spoke of the need for television studies to find passion in its engagement, and it might seem that my estimation of the negativity in popular culture is a form of downbeat bleakness. But critique can itself be passionate. As Antonio Gramsci asserted, “Pessimism of the intellect” (awareness, that is, of the quite historically determined failures of our social world) is always to be balanced by “Optimism of the will” (invocation of a future beyond the promises that are reneged upon). In several of his essays on popular music, Adorno — so often thought of as an embittered sad sack who found popular culture a total closing off of spaces of resistance — suggested that cultural fads, the cynical replacing of one trend by another for purposes of renewing the market, might breed a comparable cynicism among consumers, a bitter awareness that the culture industry is exploiting their desires. Viewed pessimistically, such cynicism at the point of consumption might be another twist in the culture industry’s control of its audience — we seem often to be living in an age where systems of power can freely admit their contempt for ordinary citizens and democratic process and yet still gain the adhesion of those very citizens – but it can also optimistically suggest resistance and rejection of top-down models of cultural flow. But we then need to be clear about what culture gives us but also what it endlessly seems to take away, and about what we can consequently do regarding all the broken promises around us, ones that come to us from culture but also from broader configurations of social power.

Links

Jumping the Shark: Chronicling the Moments When TV Show Go Downhill

Homepage of the Hunted: Unofficial Website of the Fugitive

Image Credits:

1. Fonz Jumps the Shark

2. TV Skull

Please feel free to comment.