Person to Person and Home to Home: TV News in the Pandemic

Deborah L. Jaramillo / Boston University

There has been some discussion in the trades of the innovations cable news has adopted to enhance coverage of the 2020 pandemic. Of concern is whether the news channels will retain these innovations in order to sustain their higher-than-usual ratings after this coverage gives way to something else. The idea of an “after” for a crisis of this magnitude and the coverage that has benefited from the horror of it all recalls, in crass terms, the scrambling that occurs when a channel has ridden high on a hit and must contemplate the follow-up. Television news has a hit on its hands when things go horribly wrong; it then proceeds to organize the disarray and process it through different personalities and program types throughout the day. Flow, which I’ll touch on in just a bit, is a key factor in the weight of a TV news narrative, and in the case of the pandemic, so is emotion.

News coverage of COVID-19 has flocked to micro-level stories. The unequal distribution of the virus across the country has made this not just one global or national story but an agglomeration of many different local stories made visible and televisual by homemade media. Selfies and video diaries of healthcare workers and other workers deemed essential made regular appearances on the news in the early days of the pandemic, as anchors and hosts ceded time to the people with exclusive access to the unfolding disaster.

From March through May of 2020, at the height of the first wave of the virus in the U.S., we saw samples of intimate self-disclosures in response to the violence perpetrated by politicians and systemic failures. We heard private feelings in stolen moments in cars, hospital corridors, and offices. Without a doubt, this was free content that added drama to a newscast. As media artifacts, though, they were not just one thing with one implication. They function in a few fascinating ways. They expanded the range of expression permitted on the news to include tearful seriousness—an acute and emotional awareness of the crisis and its consequences. They linked that emotion to the expertise of medical professionals, many of them nurses. And they demonstrated the accumulation of frustration and pain that cable news has embraced via flow.

If we can even begin to talk about the “after” of the programming event that is the pandemic, then that “after” has to be located within an assessment of the current state of television news. In other words, the imposition of an “after” butts up against what I have observed to be a shift in the mode of reporting on cable news. This shift is really in some ways a return to the early experimental format of the Satellite News Channel, described by Margaret Morse as “constant[ly] breaking and ever-changing.”[1]

Early and important work by Mary Anne Doane characterized television news programming as an “endless stream of information, each bit (as it were) self-destructing in order to make room for the next.”[2] Recently I have argued that in the Trump era, cable news flow departs from early formulas of repetition and fragmentation. It doesn’t repeat so much as it dwells. If repetition is about reminding, dwelling is about remembering. Flow on cable news, then, is “about memory and magnitude—not the resolution of but the accumulation of politically charged information, crises, and catastrophes across the day and, as we are seeing, across all days.”[3] Coverage of the recent protests in Minnesota, for example, never strayed very far from the context of COVID-19. Images of masked protesters, as well as reporters’ anxieties about social distancing in a crowd, reminded viewers of the damage done to black and brown bodies by the police, systemic racism, and the virus.

My work on news flow focused on politics, but as we have seen, the order of the day is the intertwining of politics and public health. There will be no “after” for this news event. Flow, as we now know it within this genre, will drag the events of this month into the next and the next, highlighting the consequences in the long, post-2016 narrative. But remember that there are the events themselves, and the way the events have been organized and communicated. In many ways, cable news has organized this intertwining of politics and public health for us by amplifying an emotional center located in private spaces and personal expressions.

This turn to the private and personal marks a noteworthy (though not absolute) rupture in TV news history. Traditionally, news has been regarded as a space for dispassionate discussions of public—not private—affairs. The rise of so-called opinion journalism eroded the “dispassionate” part, but the long-standing association of news with public affairs has coded it as a masculine genre, which is at odds with the medium associated so closely with women and domesticity. Consequently, it has been difficult for women to occupy positions of authority in news programming. Consider the treatment that Meet the Press creator and moderator Martha Rountree received from one viewer, who wrote in the early 1950s that Rountree “cluttered up” the show and that “this man’s job” should be filled by “a full size man.”[4]

Although women were mostly excluded from the manufactured seriousness of TV news, the visual conventions of news made their way into women’s programming. For example, Arlene Francis included a news-style “bulletin” segment in her NBC daytime show Home (1954-1957). In one surviving episode, Francis, seated in an elaborate chair behind a tastefully appointed desk, reports on women’s clubs activities and is interrupted by a producer, who hands her a breaking news bulletin about Egypt and the United Nations. Donning the most fantastic glasses you’ve ever seen, Francis reads the bulletin, ad libs a response, and ultimately tosses to Lucille Rivers for some sewing tips. In many ways a model for what would become the “soft news” space of network morning shows, the Home clip takes the trappings of a news anchor—a desk and a chair—and dresses it in femininity and domesticity, exposing the construction of staid news conventions.

Dominant attitudes about the separation of public and private affairs have not been specific to television. The discussion of private matters on early radio advice shows was once regarded by the FCC as point-to-point communication; they argued the delivery of advice to individual listeners did not satisfy the intention of broadcasting. Private matters were for the telephone. In the pandemic, the smartphone intervenes and bridges news and personal narratives.

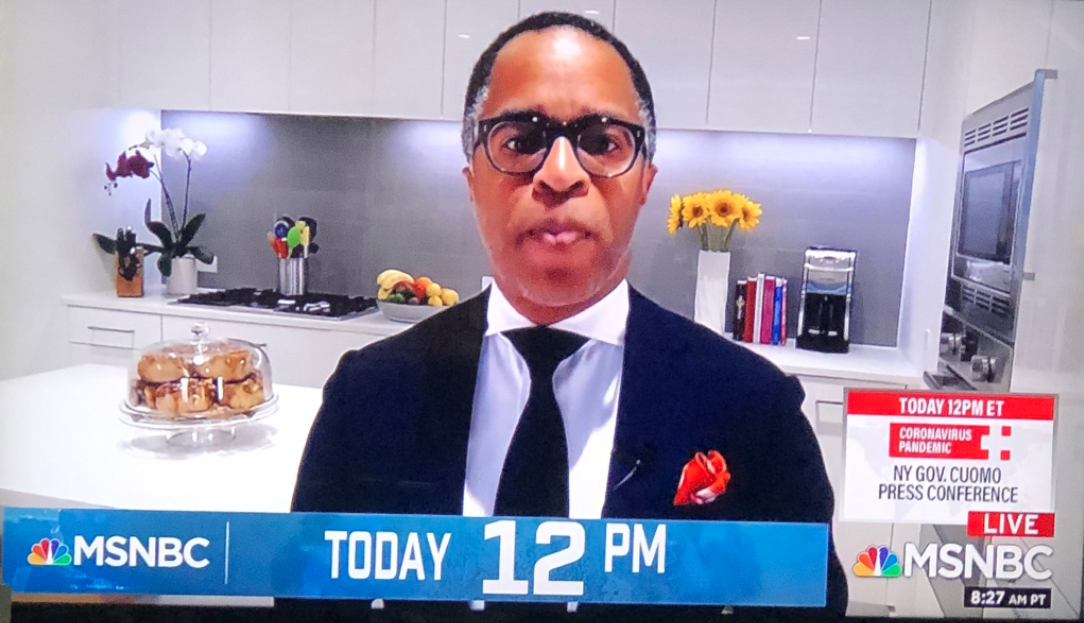

Audio-visual evidence of workers’ personal anguish in the face of a public health emergency evaporates the distinction between emotion and rationality. It’s also a very public acknowledgement that heartfelt emotion—the type of emotion associated with women—is worthy of TV news. At the same time, we’re seeing our usual TV news talking heads at home, mostly in front of bookshelves but also in living areas and kitchens. (Shout-out to Jonathan Capehart’s immaculate kitchen, pictured at top.) These glimpses into homes bring together private spaces and public affairs and chip away at the construction of professionalism as a masculine ideal that exists in a studio or in front of a bad stock image of a city skyline. What remains to be seen is if this peculiar narrativization of politics and public health, operating in and through private spaces and feelings, moves ahead in concert with relentless news flow.

Image Credits:

- MSNBC’s Jonathan Capehart broadcasting from home (author’s screengrab)

- Arlene Francis on NBC’s Home (author’s screengrab)

- A wider photo of Arlene Francis on NBC’s Home, capturing her desk and flowers (author’s screengrab)

- Morse, Margaret, “The television news personality and credibility: reflections on the news in transition,” in Studies in Entertainment: Critical Approaches to Mass Culture, ed. Tanya Modleski (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1986), 73. [↩]

- Doane, Mary Ann, “Information, crisis, catastrophe,” in Logics of Television: Essays in Cultural Criticism, ed. Patricia Mellencamp (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1990), 224. [↩]

- Jaramillo, Deborah Lynn, “Twitter Watchers: The Care and Feeding of Cable News Flow in the Age of Trump,” in A Companion to Television, 2nd ed., ed. Janet Wasko and Eileen Meehan (Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.), 248. [↩]

- Donald F. Hynes to NBC, May 8, 1952; Folder 44-3: National Broadcasting Company, New York, N.Y.; Box 61; RG 173; National Archives at College Park; College Park, MD. [↩]

Thank you for this insightful article!

Test

Thanks for your sharing insightful article!

Thank you very much for sharing informative post here.