At the Scene of the Crime: Podcasting and Placemaking

Helen Morgan-Parmett / University of Vermont

…we have to drive back out to Woodlawn drive, turn onto Security Boulevard, which does have some big intersections you have to get through. Again, we’re trying to get to Best Buy, it’s still there today, in twenty-one minutes… We’re at seventeen minutes, we’re just crossing under the beltway… (Serial, Season 1, Episode 5: “Route Talk”)

Perhaps this quote reads familiar, if you, like me, are one of the 175 million listeners of the world’s most popular podcast, Serial. It is the episode where Sarah Koenig, Serial’s narrator, and her producer, Dana, drive the suspected route Adnan Syed drove on the day he supposedly murdered his ex-girlfriend, Hae Min Lee. Sarah and Dana drive the route to determine if the state’s timeline is possible. As listeners, we move through Baltimore County along with them, listening to the sounds of traffic and the hum of the car’s engine, as they make the turns necessary to arrive at their final destination—a Best Buy parking lot where Syed is suspected of committing the murder. Although I have not personally driven the route, apparently lots of other people have, and not just on their daily commutes, but in a purposeful attempt to recreate the route themselves as amateur sleuths or as tourists looking for a Baltimore excursion off-the-beaten-path.

Like Serial, many podcasts, especially (but certainly not limited to) the true crime genre, have a strong sense of and connection to place. The Gimlet produced Crimetown podcast, for example, has dedicated its two seasons to Providence and Detroit respectively. Studio recordings are supplemented with on-location work that details in multisensory fashion not only the stories of the cities’ crime histories, but also the cultural and social geographies that provide the contexts for those crimes. In the Dark’s second season takes us to Winona, Mississippi to investigate the possible innocence of Curtis Flowers, exploring a racist and classist criminal justice system inasmuch as how race and class biases manifest in the places essential to life in small-town America.[1] Similarly, the wildly popular S-Town, from the makers of Serial and This American Life, is ostensibly a character study of John B. McLemore, but undoubtedly the “shit town” for which the podcast is named, Woodstock, Alabama, is as much under study as McLemore.

I could name many other podcasts, both within and beyond the true crime genre, that work to produce a very specific and intimate sense of place for listeners. Yet little scholarship has addressed podcasting’s production of place. Instead, most scholars emphasize the space- and time-shifting capabilities of the medium, as it enables listeners to download and listen when and where they want.[2] A core component of this discourse ties podcasting’s mobility to its potentially democratizing and empowering capabilities, as it “puts the onus on the listener, whose jurisdiction over the when, where and how of podcast engagement…suggests a highly liberated, even democratized consumer experience.”[3]

This understanding of podcasting’s relationship to space and place follows a well-trodden discourse of media space, which overwhelmingly theorizes media as a space-compressing or despatializing technology.[4] However, as I have argued elsewhere, this view obscures the ways media produces both symbolic and material spatialities. Although podcasting does produce space- and time-shifting, these shifts are less a matter of compressing space or evacuating place than they are a means of creating new relationships to place and new forms of emplacement.

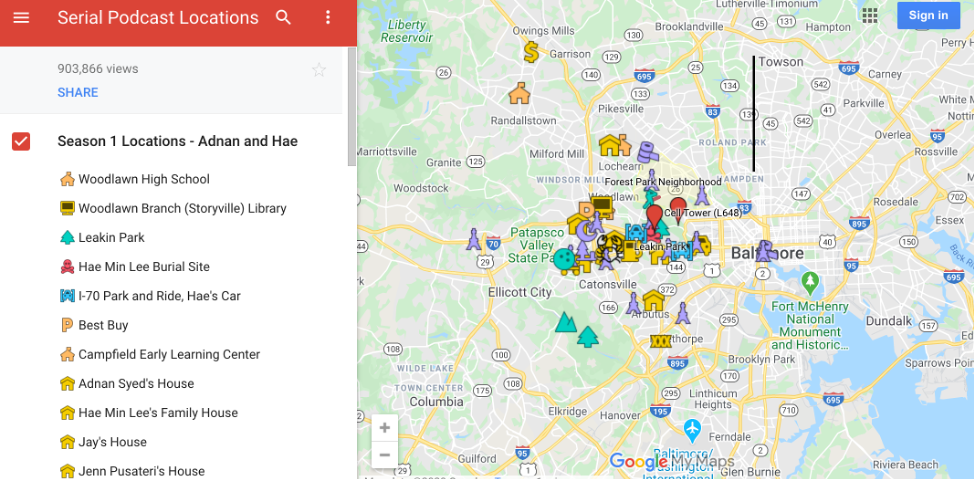

Podcast emplacement is especially constituted through its sensorial, affective intimacy in conjunction with its multiplatform convergences. For example, while Serial’s popularity demonstrated some of the core aspects of the time- and space -shifting potentials of the medium, the podcast was also inconceivable without its deep ties to the spaces and places of Baltimore County, giving listeners an intimate feeling of “being there.” As Sarah and Dana drive the route, the on-location recording affectively connects the past of the crime to Sarah’s and Dana’s present through a soundscape that brings listeners to the site of the crime. Aural cues are accompanied by other sensibilities of place that can be accessed through multi-modal, interactive, and convergent media, whether through social media and endless Reddit threads that meticulously map and annotate the crime scene, Serial’s website’s maps and documents, YouTube videos of fans driving the infamous route, taking your own tour or following someone else who did, amongst many, many other intermediations of the podcast. Some scholars have argued that podcasting’s intimate and deep listening creates a detachment from the place of listening, arguing, for example, “It would be difficult to navigate city streets, or busy traffic, and not fall into ‘rabbit holes.’”[5] But listening to the podcast at the place of production and at the site of the narrative—a kind of media pilgrimage[6] —can actually increase intensity in ways that further connect the listener to place, rather than disconnecting them. The podcast is the map that guides the listener’s navigation of the city street rather than the rabbit hole.

Although emplacement might be an unintended effect of most podcasts, there are also more explicit attempts to use the sensorial, affective, and convergent capabilities of podcasting as a purposeful means for connecting listeners to place. In the case of the performative podcast Wandercast, artist Robbie Z. Wilson “invites listeners to take it on a wander. It employs podcasts’ portability and aural intimacy to unearth playful affordances inherent in our surroundings and to encourage enaction of those affordances as a means of rediscovering one’s environment.”[7] This performative playfulness depends on a lack of site-specificity on the part of the narrator, but their displacement is aimed to provide an embodied and site-specific experience for the listener.

In addition to performance art, community journalism is an area ripe with podcasts whose explicit aim is to connect listeners with place-based communities. Brave Little State, a podcast produced by Vermont Public Radio in my own place in the state of Vermont, enjoins listeners to pose topics related to Vermont that they are interested in investigating, and all listeners get to vote on what topic they want the podcast to explore.[8] The listener who posted the question then joins with the host to investigate, on-location, the answers to their question. Topics include questions like “Why is Vermont so white?” and “Those aging hippies who moved to Vermont…where are they now?”

I contend podcasting produces a kind of “atlas of emotion,” what Guiliana Bruno refers to as a haptic mapping and a “phantasmatic structure of lived space and lived narrative; a narrativized space that is intersubjective.”[9] Bruno is referring to cinematic mapping, but there is much to be gleaned about podcasting from her groundbreaking work on cinematic history and its production of new forms of “emotive, embodied and visceral engagement with space.”[10] While podcasting’s intimacy and connectivity is often theorized as an effect of its space compressing or mobile practices that collapse distances between producer and listener, I suggest we might instead consider how podcasting’s connectivities and intimacies are forged out of the production of emplacement in a variety of forms. We then might explore how podcasts, in their multisensorial, convergent engagements produce new forms of interacting with, embodying, living, understanding, and navigating the spaces and places of our everyday, mediated lives.

Image Credits:

- Serial highlights the places that are central to the narrative in this crime scene photo overlain with Serial’s logo.

- The Best Buy parking lot, pictured here, has become a tourist site of sorts after the Serial podcast and was featured as one of many series-related locations in The Guardian to give fans a better idea of what these sites looked like. Many other media outlets along with fans on social media participate in sharing these kinds of images as well.

- Reddit users produced numerous maps of the locations in Baltimore County central to Serial, including this comprehensive map that identifies sites on the map for reader-listeners to visualize distance, how places interconnect, and connect to the state’s timeline and theory of events.

- Logo for Vermont Public Radio’s Brave Little State podcast, which connects listeners to a sense of local community.

- Interestingly, in Episode 2, listeners are enjoined to explore the route, much like in Serial, Flowers allegedly walked the morning of the murders. [↩]

- See, for example, Berry, Richard. “Will the IPod Kill the Radio Star? Profiling Podcasting as Radio.” Convergence: The International Journal of Research into New Media Technologies 12, no. 2 (May 2006): 143–62. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354856506066522; Funk, Marcus. “Decoding the Podaissance: Identifying Community Journalism Practices in Newsroom and Avocational Podcasts.” International Symposium on Online Journalism 7, no. 1 (Spring 2017): 67–87; Llinares, Dario, Neil I. Fox, and Richard Berry. Podcasting : New Aural Cultures and Digital Media, 2018. Jan Lauren Boyles case study of how digital news in post-Katrina New Orleans created fields of care that facilitated urban attachment is an exception, as they explore various podcasts that connect people of New Orleans to each other and who use podcasting as a means of digitally connecting to place and constituting place identities. However, Boyles’ exploration is less about podcasting per se and more about digital journalism more broadly, though I am interested in how these insights about urban attachment might speak to the specificity of podcasting’s spatial practices. See Boyles, Jan Lauren. “Building an Audience, Bonding a City: Digital News Production as a Field of Care.” Media, Culture & Society 39, no. 7 (October 2017): 945–59. https://doi.org/10.1177/0163443716682073. [↩]

- Llinares, Dario. “Podcasting as Limited Praxis: Aural Mediation, Sound Writing and Identity.” In Podcasting : New Aural Cultures and Digital Media. Palgrave MacMillan, 2018, 127. [↩]

- See, for example, Harvey, David. The Condition of Postmodernity: An Enquiry into the Origins of Cultural Change. Oxford [England]; Cambridge, Mass., USA: Blackwell, 1989. [↩]

- Hancock, Danielle, and Leslie McMurtry. “‘I Know What a Podcast Is’: Post-Serial Fiction and Podcast Media Identity.” In Podcasting : New Aural Cultures and Digital Media. Palgrave MacMillan, 2018, 90. [↩]

- Couldry, Nick. The Place of Media Power Pilgrims and Witnesses of the Media Age. London; New York: Routledge, 2001. [↩]

- Wilson, Robbie Z. “Welcome to the World of Wandercast: Podcast as Participatory Performance and Environmental Exploration.” In Podcasting : New Aural Cultures and Digital Media. Palgrave MacMillan, 2018, 274. There are numerous other examples of podcasts aiming to either connect listeners to their surroundings, direct them as tourists, or explore the idea of the sense of place. [↩]

- Brave Little State was influenced by a very similar podcast out of Chicago, titled Curious City. [↩]

- Bruno, Giuliana. Atlas of Emotion Journeys in Art, Architecture and Film. New York: Verso, 2011, 65. [↩]

- Mazumdar, Ranjani. “The Mumbai Slum: Aerial Views and Embodied Memories,” Mediapolis, Vol 4(3), https://www.mediapolisjournal.com/2019/11/the-mumbai-slum/. [↩]

Pingback: Convocatorias en publicaciones científicas – FACSO Educación Virtual