Margaret Cho’s Televisual Trajectory: From All-American Girl to The Cho Show

Jane Park / University of Sydney, Australia

Margaret Cho’s “semi-scripted” reality series, The Cho Show, which aired on VH1 in the 2008 fall season, opens with the comedian introducing herself against a backdrop of rapidly edited clips from her stand-up routines. In the voiceover Cho positions herself within and across a number of cultural binaries – as “a comedian who yo-yoed between skinny and fat”; as the star of the first Asian-American sitcom who was deemed “too Asian for Hollywood and not Asian enough for Asian audiences”; and as a Korean-American performer caught between listening to the messages of her “traditional parents” and those of the entertainment industry. The opening credits end with Cho on stage declaring, “Now it’s time for me to do it my way. It’s my show now” to the applause of her proud parents. As she takes a bow in characteristically flamboyant dress, Cho invites us to see how far she has come since the cancellation of All-American Girl, her first television show, in 1994.

The new show promises to deliver a campy, diva-esque version of the Asian-American celebrity that more closely mirrors her stage persona as a polymorphously perverse “fag hag” who spits sharp critiques of sexism, racism, homophobia, and fatism using risqué humor and wry, well-timed observations of popular culture. In contrast to the family-friendly sitcom, All-American Girl, the tongue-in-cheek pseudo-reality format of The Cho Show seems to offer a televisual space more conducive to the transgressive jokes and self-reflexive irony that define her stand-up comedy. It also gives Cho a second chance at TV stardom, this time, with more life experience and creative control.

The Cho Show, then, can be seen as the pinnacle of Cho’s comeback, beginning with her successful 1999 one-woman show, I’m the One that I Want, in which she brilliantly critiques both the normative ideologies of (thin, white) beauty endorsed by Hollywood and the culturally essentialist notions of authenticity prescribed by the Asian-American community. Deftly mixing pain and humor, Cho recounts the trauma she experienced as an idealistic young rising star forced to undergo dangerous dieting measures to play herself on the small screen and to bear what cultural scholar Kobena Mercer has called the “burden of representation” for a highly critical Korean-American audience.1 A groundbreaking first for television and the Asian-American community, All-American Girl remains the only U.S. sitcom to focus on an Asian-American family using an all-Asian cast.

That said, it was riddled with flaws. While the show was based on her immigrant family, Cho was the only actor of Korean descent in the cast, and the writing and production team was entirely Anglo-American except for one Chinese-American writer. The producers did not bother to do the research necessary to effectively target its Asian-American audience, and in their effort to garner high ratings, tried to target too many demographics at once. As a result, the show suffered from narrative clichés and underdeveloped characters: the actors often self-orientalized, performing their Asianness as a gimmick, which could have been quite funny except that these performances were almost always played straight. Ideologically, All-American Girl also reinforced the banal binary of assimilation (“American”) versus tradition (“Asian”), tellingly embraced by both politically correct white liberals and culturally conservative people of color. In doing so, it lost the opportunity to explore the provocative and often entertaining experiences that arise from having a culturally hybrid identity – experiences that would have been recognizable to many second-generation Asian Americans and perhaps compelling to viewers of other ethnicities as well.

Commercial failure might have been inevitable, however, given the historical and industrial contexts of the show’s airing. All-American Girl was situated awkwardly in a period when television was moving toward but had not yet entered the post-network era. As television scholar Amanda Lotz notes, Horace Newcomb and Paul Hirsch’s concept of television as a “cultural forum” – or a mediated public sphere bringing together multiple, heterogeneous viewers – began to dissolve in the mid-eighties as more Americans subscribed to cable and satellite TV and as new networks Fox, the WB and UPN competed with the original three.2 These developments were part of a larger cultural shift in the U.S. toward niche-marketing, which interpellated members of historically marginal groups as consumer-citizens. We see the culmination of this shift in such programs as Showtime’s Queer as Folk and The L Word, which target queer audiences and UPN’s Girlfriends and Everybody Hates Chris, which target African-American ones.

Like these shows, The Cho Show is pioneering insofar as it renders visible identities and groups that have had little and/or stereotypical presence on television and insofar as it gives members of these groups the power to tell their own stories. At the same time, however, the shows must tell those stories using the neoliberal terms of the media industry and dominant culture that, one could argue, their very presence critiques. As well, the audiences are often self-selected based on the branding and programming strictures of the particular channels on which they air. Given these restrictions, what kind of political or cultural work do such shows perform? For instance, we might ask: how and to what extent does The Cho Show differ, ideologically, from All-American Girl?

I would answer: not much. The eight episodes that comprise the first (and final) season of The Cho Show highlight different aspects of Margaret’s life as a Hollywood celebrity who spends most of her time hanging out with her parents (who live with and seemingly off her), vivacious little person personal assistant and conventionally fab entourage of gay male stylists. Most of the material focuses on issues of beauty, celebrity, consumerism, gender and sexuality. In one episode, Margaret tries to court the paparazzi by making a sex tape and cutting a pop single; in another, she considers undergoing plastic surgery to combat the aging process; and in yet another, she gets a g-shot followed by a colonic, to exorcise the ghost that she is convinced is haunting her vagina and giving her writer’s block (ok, this is kind of funny …). In these episodes, the topic of ethnic identity tends to be relegated to her parents’ anecdotes comparing Korea and the U.S., which provide the show with some of its most hilarious and evocative moments and which, sadly, are reduced to quirky tag lines.

While the role of the ethnic other, then, is projected onto and embodied by her parents in the episodes that are supposed to represent the star’s quotidian life, Margaret’s ambivalence about being Korean-American, strikingly (and literally) frames the series; it is spectacularly showcased in the first episode when she accepts the KoreAm “Korean of the Year” award and in the last, when she is honored with her own day in San Francisco. In both episodes Margaret is forced to recall painful memories of being unable to fit the “model minority” role typically assigned to Asian Americans. Rather unsurprisingly, she makes peace with these bad memories when the communities that once rejected her publicly acknowledge and applaud her success. Much like her character in All-American Girl, the older Margaret of The Cho Show epitomizes the American immigrant dream, in which one gains cultural citizenship by conforming to certain ideological norms. In her first show, that norm was a sitcom version of assimilated “All-American” identity; in the second, it is a reality TV version of “post-racial” Hollywood fame.

Yet there has been a shift. Whereas in All-American Girl racial and ethnic difference was a political burden to be borne, in The Cho Show it has become an affective (and effective) ornament to complement – and celebrate – one’s celebrity. While this shift does not necessarily reflect larger cultural developments in the U.S. around issues of “race,” it certainly seems to speak to them.

Image Credits:

1. Margaret Cho.

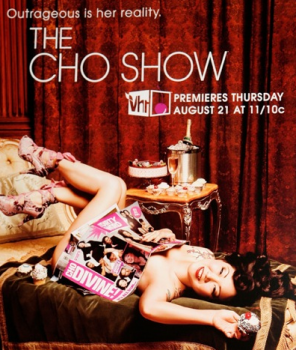

2. Cho in control.

3. All-American Girl: pressures of identity and assimilation.

Please feel free to comment.

Thanks for the insightful column. I think you bring up a lot of important issues to consider when discussing how star images navigate certain identities.

Thanks Kit. I’m working it into a longer essay – so looking forward to suggestions and critique from readers :)