OVER*FLOW: The Oscar’s Slow Lurch Toward Relevance and Diversity

Shawna Kidman / University of California San Diego

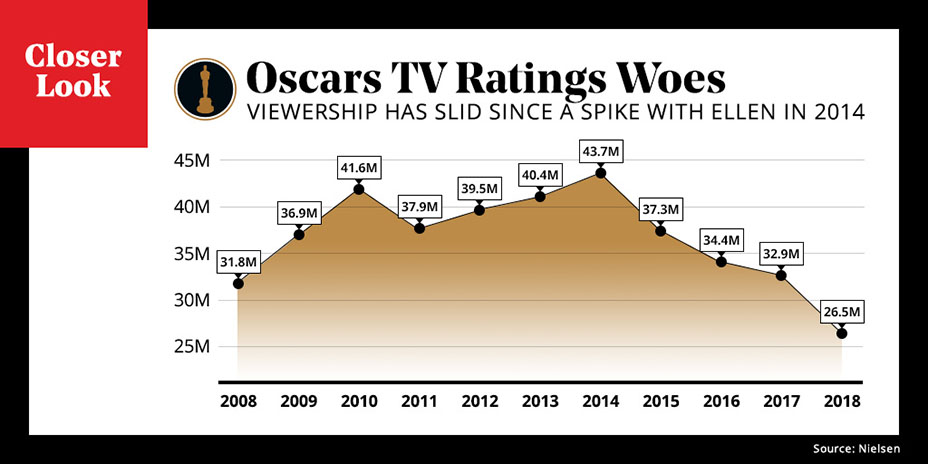

The Academy of Motion Pictures was on a mission to save the Oscars this year. First up was the awards’ well-established popularity problem. Ratings for the telecast were at an all-time low in 2018, with only 26.5 million viewers, down dramatically from 43.7 million just a few years earlier. But numbers weren’t the only issue; the Academy is increasingly perceived as being deeply out of touch with the moviegoing public. Nominees tend to be small films (low in budget, low in box office take) that few Americans have seen, or sometimes, even head of. The Academy has been trying to solve this problem since at least 2008, when they expanded the Best Picture category from 5 to 10 films; Dark Knight Returns had failed to receive a nomination, and seemingly as a result, the ratings took a hit. This year, looking to further expand the range of films recognized, the Academy leadership floated the idea of a whole new category for best “popular” film. Like their other ill-conceived announcements, including pushing cinematography and editing awards into commercial breaks, the proposal was basically dead on arrival with exasperated Academy members. Also of concern for the last several years has been the Oscars’ considerable diversity problem. In response to #OscarsSoWhite campaigns in both 2015 and 2016 (when not a single non-white actor or actress was nominated) and steady criticism for its tendency to snub films made by or about people of color, the Academy invited nearly 1000 new members this year. The explicit goal was to open its doors to more diverse voters.

At first, these efforts seemed to be paying off. The list of nominees included some very popular films—Bohemian Rapshody, A Star is Born, and Black Panther—as well as some very diverse films, including BlacKkKlansman, If Beale Street Could Talk, and again, Black Panther. And in the end, ratings went up, by 12%. But it remained the second-worst rated Oscars ever, and the Best Picture win went to Green Book, a film criticized for being a simplistic racial reconciliation tale. A throwback to prior disheartening winners (e.g. Crash or Driving Miss Daisy), the movie reminded everyone that the Oscars’ hoped-for-changes, if they come at all, are likely to materialize very slowly. There’s also the not-so-small fact that the Academy can only give Oscars to films that actually get made (and have enough support from their distributors to receive massive awards-season marketing campaigns).

For this reason, Black Panther stands out to me as a particularly intriguing Oscar contender. As an incredibly popular and genuinely diverse film, it was everything the Academy wanted and needed this year. But back in early 2016, when Disney, Marvel Studios, and producer Kevin Feige hired Ryan Coogler to direct the film, they likely weren’t thinking of racking up Oscars. They had plenty of other reasons to greenlight the project though, which had been in and out of development since the mid-1990s. Marvel was facing condemnation for, among other things, its failure to build a superhero film around anyone other than a white male; around the same time, DC responded to similar criticisms by finally prioritizing Wonder Woman, which also proved very successful both critically and financially.[1] As Marvel tells it then (or at least as their PR machine claims), this was a relatively easy decision on the part of producers. What’s more interesting and perhaps surprising, then, is the fact that the young and extremely talented Ryan Coogler agreed to sign onto the film. Ava DuVernay had already turned down the job (she decided instead to make A Wrinkle in Time, also for Disney). And Coogler, whose debut Fruitvale Station became a Sundance darling, and whose critically acclaimed Creed had just passed the $100 million mark, had an enviable position in Hollywood and the power to pick his next project.

He chose Black Panther, a franchise film with blockbuster potential. Although tellingly, he did not approach it like a typical comic book film. Coogler selected a mostly African and African-American cast and a diverse creative production team with experience from the indie world. It included two women of color, Ruth E. Carter and Hannah Beachler, who ultimately won Best Costume Design and Best Production Design in two of Oscar night’s most gratifying moments. As far as the film’s creative process, when Coogler describes its conception, it’s almost always in terms of his cultural identity, his background in Oakland, and his ancestral roots in Africa. Although we can assume he researched old comics before writing the film, in interviews, he always chooses instead to point to his more significant preparation, an exploratory trip to Sub-Saharan Africa, which helped him better understand the region’s traditions, landscapes, and struggles. In the end, he made a political film, with a progressive message about colonialism and about black life in the U.S. and abroad. Of course, as a comic book movie, Black Panther is also action-packed, visually dazzling, and brimming with witty one-liners.

In the past, we may have expected to see a creative team like Coogler’s—filmmakers with a distinct vision and clear message—assemble around a movie in a more traditionally respectable genre (perhaps a literary adaptation or a war film), or in other words, conventional Oscar-bait. But if they had, nobody (at least outside of LA or NY) would have seen their vision or heard its message. The serious-minded mid-range films of the past, movies like Dances With Wolves (1990) and Silence of the Lambs (1991), that won both awards and audiences, have largely disappeared; they’ve become the exception instead of the rule. The studios gradually turned instead toward tentpoles. And then, beginning in the early 2000s, they doubled-down on the strategy, building up on private equity-funded slate financing, transmedia storytelling, and IP-based franchises. Comic book films moved to the center of a new multimedia mode of production in Hollywood and they remain there today.[2] Meanwhile, the awards shows have been left to lower-budget “indie” films, a space that’s been relatively easy for companies like Netflix and Amazon to break into (despite an ever-evasive Best Picture win). But if a filmmaker is interested in reaching big audiences and big buzz, Netflix cannot get them there. Comic books and franchises are the only way to access the masses, largely because they’re the only products Hollywood studios will put the full weight of their considerable machinery behind. That Black Panther was the very first comic book film nominated for Best Picture shows how out of touch the Academy is, not only with the American public, but with Hollywood itself, which, as an ecosystem, has come to depend on the lifeblood of superheroes.

In the future, we’re likely to see more comic book movies on Oscar night. But this won’t be because the Academy itself is transforming (even if it does, ever so slowly, lurch toward the future). It will be because more gifted and capable filmmakers like Ryan Coogler and Patty Jenkins will choose audiences over awards, bringing their significant talents to big IP-based franchises—movies too big for the Academy to ignore. It’s a little ironic actually. Despite its blockbuster status, Black Panther was Coogler’s first significant showing at the Oscars; both Fruitvale and Creed were overlooked, with only the latter receiving a nomination, for the performance of Sylvester Stallone. I wonder how much that 2016 snub impacted Coogler’s decision not to chase a traditional awards film as his next project. It’s yet another reminder that if the Academy fails to fully transform and recognize diverse talent, it will make itself and the kinds of films it has historically supported even more irrelevant.

Image Credits:

1. The Hollywood Reporter on Oscars’ Declining Ratings

2. Twitter Reacts to Chadwick Boseman Reacting

3. Hannah Beachler’s Lovely Acceptance Speech on ABC

- There are volumes of blog posts, comment sections, and online articles from 2014 and 2015 (and also before and after that window) that make these critiques as well as track Marvel and DC’s responses to them. See, for example, Jeet Heer, “Superhero Comics Have a Race Problem. Can Ta-Nehisi Coates Fix it?” The New Republic, Sept 22 2015 and Monika Bartyzel, “White Spider-Man and Marvel’s Diversity Deflection,” Forbes, Jun 23 2015. Marvel announced Chadwick Boseman’s attachment to the role in Oct 2014 and Ryan Coogler’s involvement in Jan 2016. [↩]

- Jay Epstein, Thomas Schatz, and Harold Vogel all discuss facets of this structural transition. See Jay Epstein, The Hollywood Economist (Brooklyn: Melville House, 2012); Thomas Schatz, “The Studio System and Conglomerate Hollywood,” in The Contemporary Hollywood Film Industry, ed. Paul Mcdonald and Janet Wasko (Blackwell Publishing, 2008), 13-42; and Harold Vogel, Entertainment Industry Economics (Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2015). I also discuss this transformation, and the rise of comic book films, in my forthcoming book, Comic Books Incorporated (Oakland: UC Press, 2019). [↩]

I watched the series, it is awesome concept.

Pingback: CST Online | Call for contributions: “Over*Flow: Responses to Breaking TV & Media News”