“Scared Crazy” and Torture

Julia Lesage / University of Oregon

Since Law and Order uses “ripped from the headlines” scripts, I sometimes re-view episodes to see how the fiction develops, indeed structures, social issues I am concerned with. Recently, to study media presentations of torture, I looked again at a 2005 episode of Criminal Intent in which the script develops the issue of psychological torture in a prescient way. The episode is “Scared Crazy,” and in it, the perpetrator turns out to be a psychotherapist, Dr. Katrina Pynchon (Jennifer Van Dyck), who has driven an unstable young man to commit homicide because of her unorthodox therapeutic techniques.

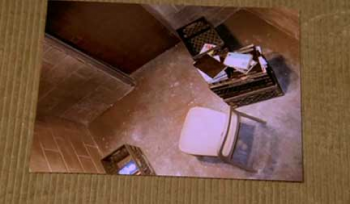

About midway through the episode, Detectives Goren (Vincent D’Onofrio) and Eames (Kathryn Erbe) search Dr. Pynchon’s apartment and find in her basement a locked cell that smells of bleach and urine. The isolation unit has just a plastic chair and a few milk crates inside, a timer outside to regulate strong halogen lights, and wires hanging from the ceiling indicating where speakers were. CDs of house music and babies crying sit in a crate on the floor. The young murderer, Robbie Boatman, spent his two weeks vacation in that place.

Goren and Eames then find out that Pynchon had been in the military as a SERE instructor at Fort Bragg, teaching soldiers resistance techniques to use if they were captured (SERE = Survive Evade Resist Escape). Upon discharge, she went to medical school, and later she was called up as a reservist, this time supervising interrogations at Guantanamo. In the episode’s climactic scene, the detectives make Dr. Pynchon fear they are going to torture her patient Robbie with the same stress techniques, especially loud music and blackout, that she’d used in her basement cell and earlier at Guantanamo. The detectives and Pynchon are together in the observation room next to Robbie’s interrogation room. Goren closes the blinds to cover the one-way mirror and Eames indicates she’s going to pipe loud house music into the room where Robbie is. In this scene, the scriptwriter, Diana Son, gives the detectives and Pynchon these telling lines:

Goren: The Hippocratic oath? How did that square with what you did in Guantanamo?

Pynchon: What do you know about that?

Eames: We know about your nightmares, your guilt…

Goren: … that you were torn between two loyalties, your oath and your country. They expected you to do things there that were against your medical ethics.

Pynchon: We are fighting terrorists…

Goren: … with terror. What does that make me? Is that what you asked yourself?

Pynchon: I set limits on the interrogations.

Goren: So it was your limits, your ethics, that were being pushed back. They were using you.

Pynchon: If I hadn’t been there, it would have been much worse.

Goren: They were using the position you were in as a doctor. The prisoners trusted you. They trusted their doctor.

Pynchon: They told me what they were afraid of.

Goren: And then you told the interrogators.

Pynchon: Yes, I decided how much noise, how much light and darkness to subject them to. I monitored their stress levels to maximize their terror. It was my job, my job.

This fictional summary of the work of military psychologists in Guantanamo’s BSCT teams (called Biscuits = Behavioral Science Consultation Teams) points to a real life struggle that was to take place inside the American Psychological Association (ASA) to have participation in interrogations prohibited as part of association policy. As with the American Medical Association, the American Pyschiatric Assocation, and the American Nurses Association, such policy decisions are important because membership in these associations is tied to state licensing and securing professional liability insurance. Significantly, the latter three organizations understood the power for abuse that working with the CIA and military in interrogations entailed well before the APA did and wrote broad policy statements prohibiting any kind of participation in abusive treatment of detainees.

Part of the reason for this battle for influence within the APA is that first the CIA and more recently the military have had a long-standing interest in drawing upon behavioral psychology as a tool for interrogation. There is an history and current practice of psychological torture, especially by the CIA, which is detailed in Alex Gibney’s excellent documentary, Taxi to the Dark Side, and in Alfred W. McCoy’s book A Question of Torture, which traces the development of an uniquely U.S. style of “no touch” torture through psychological means, particularly sensory deprivation, enforced lack of sleep, and forced standing or “stress positions.”

In contemporary times, in its everyday operation the U.S. military employs many behavioral psychologists and has a history of close ties to officials of the APA. In 2005, for example, the APA President responded to concerns about psychologists participating in abusive interrogation by setting up a panel on Psychological Ethics and National Security. Six out of the ten appointed panelists had direct ties to the military or U.S. government and of those six three had had command positions at places such as Guantanamo where abuses occurred. The panel concluded, in spite of the strong protests of some of its members, “It is consistent with APA Code of Ethics for psychologists to serve in consultative roles to interrogation and information-gathering processes for national security related purposes.” As a consequence, this APA panel’s report was later included along with the training manuals given to the BSCT teams.1

Such practices inside the APA have led to massive organizing efforts for a counter-offensive by progressive APA members, the running for APA President of an explicitly anti-torture candidate, and finally in the summer of 2008, the passing of a referendum putting a strict limit on how psychologists may work for the U.S. military or CIA. Now it is part of APA rules that psychologists may not work in settings where “persons are held outside of, or in violation of, either International Law (e.g., the UN Convention Against Torture and the Geneva Conventions) or the US Constitution (where appropriate), unless they are working directly for the persons being detained or for an independent third party working to protect human rights.” That is, they cannot work at Guantanamo or “black sites.”

What interests me about the “Scared Crazy” episode is how it places the key political argument, later taken up within the APA, by using the words of that argument as the drama’s climactic lines. In this episode, a position counter to the one Goren articulates is relegated to a few early lines by the Captain, that what goes on in Guantanamo probably isn’t a factor to consider here since, after all, “war is hell.” In 2005, only a minority of viewers knew about the BSCT teams. For this reason I think it’s rare to find a TV episode where the issues are put so clearly and are, in effect, the last word.

Image Credits:

1. Dr. Katrina Pynchon – Author Screenshot of Criminal Intent

2. Pynchon’s patient, Robbie Boatman – Author Screenshot of Criminal Intent

3. Forensic photo of cell where Robbie was held – Author Screenshot of Criminal Intent

4. Forensic photo of halogen lights in ceiling of Robbie’s cell – Author Screenshot of Criminal Intent

5. In the observation room, Pynchon can no longer see Robbie and fears for his sanity. – Author Screenshot of Criminal Intent

6. Goren shows emphatic emotion when he talks to her about her work at Guantanamo. – Author Screenshot of Criminal Intent

7. Front Page Image

Please feel free to comment.

- see letter of APA members in opposition at http://www.counterpunch.org/apa06072007.html [↩]

I found this article to be really rather interesting from a number of points, but I would like to highlight two.

First, while the tag line “ripped from the headlines” has been deployed by the various iterations of “Law and Order,” I have found some of the “artistic license” taken by the writers to be eerily prescient. In other words, while the writers work from a core story concept taken from a cultural cue, they will often develop the underlying issues to such an extent that they predict the logical outcome of such issues (i.e. torture, child abuse, sex traffiking, and school violence have all been issues that have allowed L&W to both explore the present and predict future trajectories). I found this aspect of your article to be well-thought out. Are you planning on expanding this?

The second issue that emerges is the underlying anti-intellectual and anti-professional underpinnings of many of these shows, in large part reflective of current cultural attitudes. This is far from the only episode in a L&W show to posit a psychologist as a villain. College professors, lawyers, stockbrokers, and many other professionals are often the ultimate villain, after the requisite misdirection toward a more middle or working class suspect. This seems to be in concert with a mistrust of authority that ranges from Scientologist questioning the legitimacy of psychiatry to those who question evolution, global warming, and the government’s role in 9/11. It is but a small reflection of an overall anti-rationalist sensibility that currently pervades culture in the US. The one group, particularly on prime time television, that is immune from this is law enforcement, whose reason and logic solve crimes and are perceived as “useful.”

Great article.

Erik, thanks for your observations. I am writing about torture and film, but about documentaries. Of great interest to me in your comments is the idea that past media on social issues become interesting to us to the degree that they predict future trajectories. There is so much documentation surrounding the torture sponsored by the US Government that people use documentaries, newscasts or talk shows as summary media. Fewer people dig into the many good books on the subject or the primary documents.

In the case of feature length documentaries or docudramas — Taxi to the Dark Side, Standard Operating Procedure, Torturing Democracy, Ghosts of Abu Ghraib, and Road to Guantanamo — a 90-minute viewing gives a viewer the needed summary, and in the case of these films it is quite a good summary. The films vary in style, effect, and artistic quality as well as in the specific aspects of the problem that they emphasize. But in retrospect, they will probably also be judged by their predictions. As a matter of fact, we are also now going back to Judgment at Nuremberg or Battle of Algiers for the same reason, to get an historical perspective on governments, individuals, and torture; we look at these films from the past in a new light, searching them for their predicative ability.

Most independent documentarists take a number of years to produce a film and another to distribute it, so they have to try to give it “long legs.” I suspect that many writers for the Law & Order franchise, knowing they want to take up a key social issue, also write with the future in mind. Interestingly, creating a good web site can bridge the gap between the spectatorial experience and the need for information and activism, and of all the films I listed above, only the film Torturing Democracy (a documentary with less “art” than the others) did that. It has a web site with a footnoted transcript of the film, a streaming video presentation of the work, and a large, annotated, updated archive of primary resources.

Thank you for bringing to my attention the ideas of prediction and an imagined future. It was that aspect of the episode Scared Crazy that made me want to return to it.

Regards, Julia Lesage