The Voices of Viki: Considering Fansubbers as Linguistic Gatekeepers

Amanda Halprin / University of Texas at Austin

According to a survey conducted in 2014 by the Korea Creative Content agency (a South Korean governmental agency that “oversees and coordinates the promotion of the Korean content industry”), an estimated 18 million Americans enjoy watching Korean dramas. In the three years since that survey was conducted, Korean dramas have grown in popularity, with large streaming platforms such as Netflix and Hulu adding a number of new Korean programs to their content libraries and specialized streaming platforms such as DramaFever seeing significant subscriber growth. The majority of these U.S. viewers are not fluent in Korean, meaning they rely on screen translations when they watch Korean dramas. Of the two main forms of screen translation (dubbing, where a text’s original audio is replaced by audio in a new language, and subbing, where a text’s original audio is preserved and subtitles are provided on screen), American viewers of Korean dramas typically rely on subbing.

When considering the role of subbing in the viewing experience, it is imperative to remember that the translation process is (somewhat) subjective. While there has been debate on the extent of translation’s subjectivity, this column takes up a viewpoint on translation put forth by Susan Bassnett and André Lefevere in their preface to Lawrence Venuti’s The Translator’s Invisibility: Translation is manipulation. Specifically, they argue, “Translation is, of course, a rewriting of an original text” and “Rewriting is manipulation.” [1] This argument raises an important question: Who are the manipulators? Answering this question is pertinent not just to the translation industry, which has seen rapid changes with the rise of online distribution methods, but also to global media consumers.

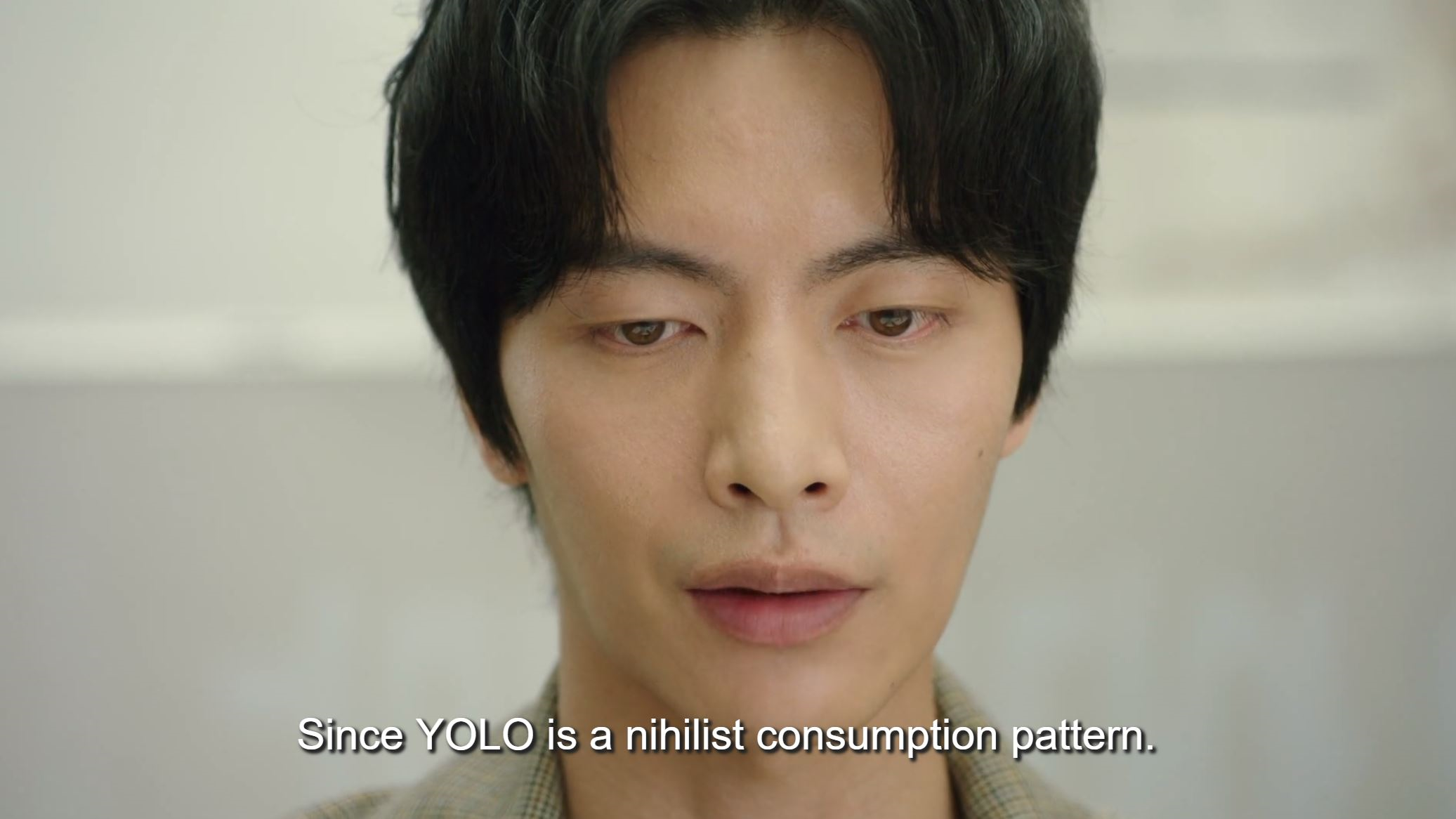

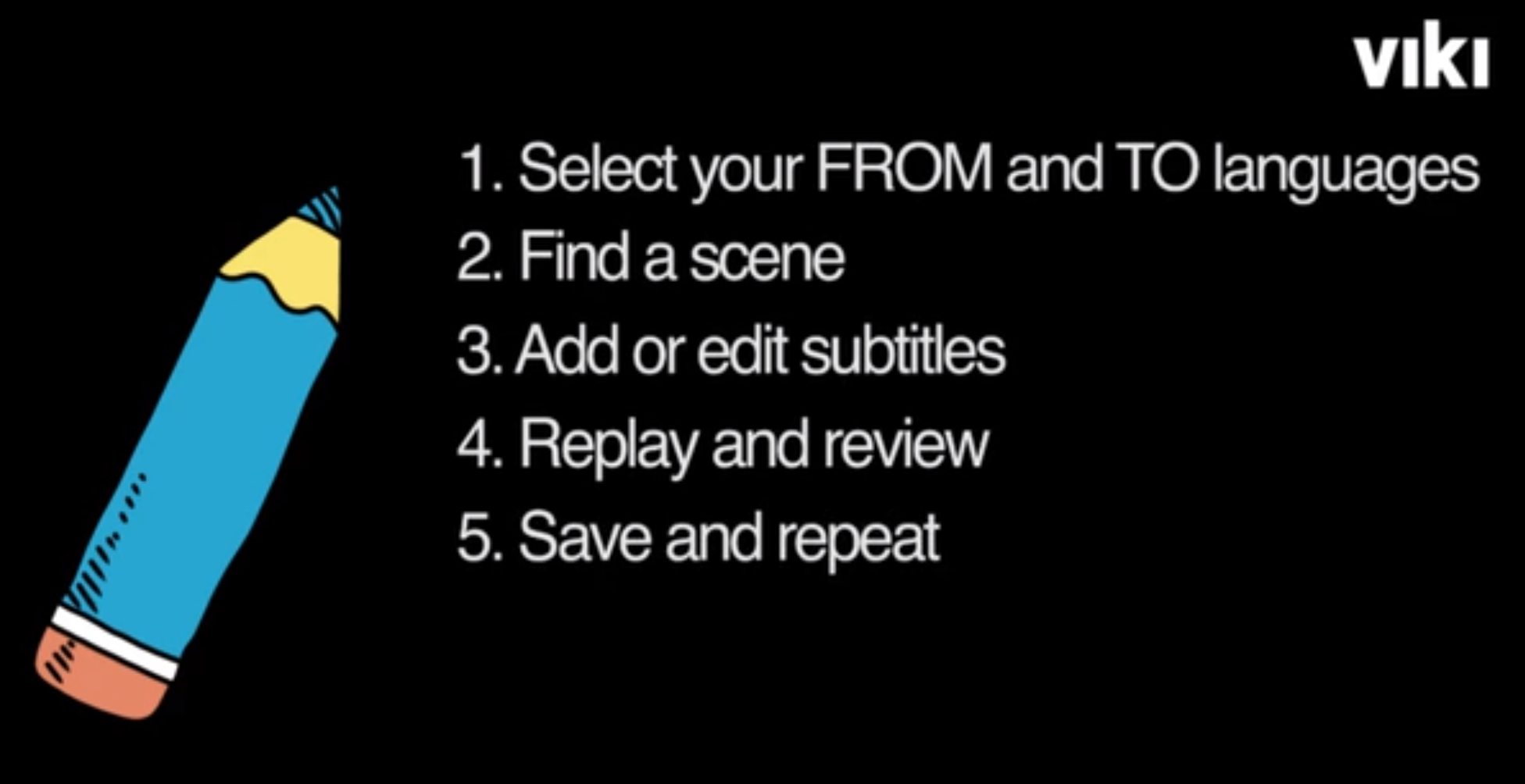

Through the rise of streaming platforms, more and more audiences have begun to consume content foreign to them. However, to fully understand how audiences receive foreign texts, it is important to understand how these foreign texts are presented. As I explored in my previous Flow column, the same source text can yield multiple translations. In the example I used, the same line was translated as “Hey, don’t you dare sing a loud English song! I’m going to kill you then!” by Viki (another specialized streaming platform), “Don’t you dare sing a loud English song!” by DramaFever, and “Hey, if you sing an English song, I will kill you. Got it?” by Netflix. The difference in translations is due to the difference in translators. While DramaFever is less explicit about its subtitling methods (the last time they publicly asked its users to sign up as subtitlers was in 2014; since then, the site has emphasized that its subtitles are written by “professionals”), Netflix uses a combination of firms hired to translate content and translators recruited using a publicly available online test [2] to write subtitles for its content. Of the three sources used in this example, Viki is the most open about its translation process. Each show on Viki has a subtitling team made up of five components: the channel manager, moderators, editors, subtitlers, and segmenters. The channel manager is responsible for overseeing all translation activity for a show. Moderators are appointed to supervise a specific language’s subtitling process (e.g., the English moderator oversees the English subtitles, while the Spanish moderator oversees the Spanish subtitles). Additionally, the moderators recruit subtitlers to write the show’s subtitles and editors to check the subtitler’s work. Finally, segmenters are responsible for dividing video into timed segments so subitlers can work on writing subtitles in pieces (as opposed to subtitling a whole text at one time). [3]

The fan-sourced model utilized by Viki presents an interesting intersection between fan and translation studies; additionally, it represents a growing trend in the distribution of online content. Although fan-produced subtitles (known as “fansubs”) have been around for decades, [4] online tools have made the practice more accessible to a larger number of fans. While fansubbing began as a way for fans to navigate around hurdles put in place by the corporate sphere that prevented them from sharing and accessing content, [5] members of the corporate sphere are now incorporating fansubbing practices into their distribution models. Of the companies utilizing fansubbing practices, Viki is perhaps the most aggressive in its incorporation of the model. The company’s “About Us” page exclaims, “Together with its fans, Viki removes the language and cultural barriers that stand between great entertainment and fans everywhere.” This corporatization of subtitling practices has allowed more fans to get involved in the subbing process. While the company does not release the number of community users actively involved in the subbing process, these fan-produced subtitles have been estimated to reach 40 million people a month. [6]

Viki claims its fansubbers have translated over one billion words in over 200 languages to viewers in 195 countries. [7] Considering the scope of Viki’s reach, the question “Who are the manipulators?” seemingly becomes more significant. The fans involved in Viki’s subtitling process are responsible for translating video for millions of viewers. Examining Viki’s fansubbers through the lens of Bassnett and Lefevere’s claim that translation is manipulation, the fansubbers appear to be gatekeepers controlling the flow of content to international audiences.

As previously mentioned, Viki’s fansubbing process utilizes five types of laborers: channel managers, moderators, editors, subtitlers, and segmenters. On Viki’s message boards, fans involved in the subtitling process have debated the difference in value between these roles, as well as the scope of these roles. One such post claims, “It’s a little known fact, but English language editors are the most important members of a team for the ‘other’ language moderators. Not the CM [channel manager]. Nor the Kor-Eng [Korean-to-English] subbers. The editors.” The poster justifies her stance by noting that the majority of non-English language subtitles on Viki are translated from English instead of the text’s source language. For example, when a Korean drama is subbed in Spanish, the subtitlers usually translate the show’s English subtitles into Spanish instead of translating the Korean audio into Spanish. The poster argues that the English editors are the most important role (as opposed to the English subtitlers) because they ensure the subtitles make sense. Another post poses the question, “What is needed for a good edit?” Exploring the nuances of the editor’s role, the original poster continues, “I am aware that some people think that you need to ‘respect’ the translation of a subber to correct a sentence till the editor ‘bleeds’…Do I need to respect a subtitle that is studded with mistakes?”

These discussions call for further exploration of the fans working to create subtitles. While previous scholarship has examined fansubs, [8] this scholarship primarily considers the practice from a macro-level, looking at its place in the global media landscape. I propose building on this scholarship by examining fansubbing practices on a more micro-level, focusing on the dynamics between the laborers involved in the fansubbing process, as well as the relationship between the laborers and the texts they work to subtitle. This type of examination would allow scholars to better understand the people involved in translating programming for international audiences, which provides insight into global flows and audience consumption practices.

A 2017 Forbes article titled, “Viki.com Is The Most Innovative Streaming Video Service You Haven’t Heard About,” observed, “Unlike the solitary ‘lean back’ experience offered by Netflix, Hulu, and Amazon, the giant ‘utilities’ of the U.S. over-the-top (OTT) content realm, Viki offers an engaging, community-oriented, lean-forward approach that has become wildly popular among young entertainment consumers…[it] distinguishes itself from the OTT utilities by encouraging subscribers to interact with the programs it offers, and with each other, to heighten the viewing experience for all.” While Viki’s current place in the streaming market is unique, the translator tests previously offered by DramaFever and Netflix suggest other services are experimenting with participatory engagement in the subtitling process. Similarly, as smaller streaming services continue to navigate their place within the streaming industry, more may begin incorporating fan labor into their business practices, particularly since fan labor is usually unpaid. [9] Viki serves as an especially useful starting point for examining fansubbing practices due to its vast scope and labor transparency. As audiovisual content continues to transcend linguistic borders, scholars should study translation sites in their examination of the evolution of global media and global audiences. To understand how audiovisual content is being shared and received worldwide, we must first understand what is being shared.

Image Credits:

All images used in this article are the author’s screengrabs from Viki’s website.

Please feel free to comment.

- Bassnett, Susan and André Lefevere. Preface. The Translator’s Invisibility: A history of translation by Lawrence Venuti. Routledge, 1995, p. vii. [↩]

- However, at the time of this writing, the Hermes website notes that this test has been closed “due to the rapid popularity and response from applicants all over the world,” putting the service at “capacity for each one of the language tests.” [↩]

- “Community.” Viki, 2018, https://www.viki.com/community. Accessed 18 June 2018. [↩]

- Leonard, Sean. “Progress against the law: Anime and fandom, with the key to the globalization of culture.” International Journal of Cultural Studies, vol. 8, no. 3, 2005, p. 282. [↩]

- Ibid. [↩]

- Dwyer, Tessa. Speaking in Subtitles: Revaluing Screen Translation. Edinburgh University Press, 2017, p. 166. [↩]

- It is worth noting that the “195 countries” statistic could be scrutinized by some, as most governmental organizations (including the CIA and the United Nations) currently recognize that the world is comprised of 195 countries, meaning that this statistic includes viewership in North Korea and Syria, two countries which U.S.-based streaming platforms (such as Netflix) cannot operate in due to U.S. government restrictions. However, as Viki is owned by Rakuten, a Japanese conglomerate, it is subject to different restrictions. [↩]

- Examples include Jorge Díaz Cintas and Pablo Muñoz Sanchez’s article “Fansubs: Audiovisual Translation,” Hye-Kyung Lee’s article “Participatory media fandom working on the disjuncture of global mediascape: a case study of anime fansubbing,” and Luis Pérez González’s article, “Fansubbing Anime: Insights into the ‘Butterfly Effect’ of Globalisation on Audiovisual Translation.” [↩]

- Viki does not pay members of its subtitling teams, noting, “On Viki, people who are passionate about the content – whether they want to collaborate with others, learn a new language, or practice their translation skills – join together to help translate shows into multiple languages.” However, they offer “special additional perks” to volunteers who contribute enough to qualify for “Qualified Contributor” status. [↩]

great post!!

Thank you for sharing.

Pingback: From K-Pop to the latest Fashion Trends: How the Korean wave became a global phenomenon – FLHS News