TV Finales: On-Demand Endings

Casey McCormick / McGill University

When Netflix released a full season of House of Cards in 2013, the online streaming company paved the way for a major shift in how TV gets made and watched. Of course, this was not the first time that TV viewers had access to the entirety of a season (or even series): on-demand technologies such as VHS, DVD, PVR, and streaming, had made TV compilation relatively common by 2013. But it was the first time that a series had been crafted with this method of distribution in mind, and the first time that the initial release of a series took the form of a full-season “dump.” Such on-demand native programming is becoming increasingly common, with Netflix’s $5 billion investment in original programming in 2016, and several other online distribution companies (e.g. Amazon, Hulu, CraveTV) all producing their own series—and in almost every case, releasing entire seasons at once.

The full-season dump model departs from the traditional industry logic of offering viewers a slow drip of content, hyping appointment viewing, and using distribution gaps and hiatuses to generate anticipation and demand for more “product.” These financial imperatives trickle down into the formal structures of television, affecting plot and character pacing, season and episode length, and expectations regarding narrative resolution. Before on-demand technologies, viewers were at the whim of programming schedules, and TV series could wield that narrative power in delightful and/or frustrating ways. Indeed, one of the recurring themes in accounts of on-demand technologies center on the idea of increased viewer control over when and how we watch content. While I agree with the fact that VOD shifts the power dynamics of media consumption, we need to interrogate more fully the repercussions of this shift—particularly when it comes to understanding our narrative desires. Therefore, I’m interested in two questions: how do on-demand native series take advantage of their distribution format to tell stories in new ways? And how does on-demand viewing change our experience of serial television, especially with regard to endings?

In 2015, TV critic Todd VanDerWerff wrote about how “Netflix thinks more in terms of seasons than episodes,” quoting chief content officer Ted Sarandos’ claim that “The first season of Bloodline is the pilot.” TV critic Alan Sepinwall has bemoaned such storytelling structures, arguing that many of these series have “no interest in differentiating one episode from the next, and just offe[r] up 13 amorphous hours of… stuff.” Sepinwall’s criticism is rooted in a deep loyalty to the television medium and an aversion to TV positioning itself as “like” literature or film. VanDerWerff, on the other hand, recognizes the Netflix model as a “new art form” that will “require a fair amount of trial and error.” The proliferation of Netflix original programming over the past two years has certainly given creators the opportunity to experiment with this storytelling form, and so the growing library of Netflix originals invites us to think about what I’m calling “Netflix poetics,” a specific set of tools and tactics for creating meaning in televisual narrative. [1]

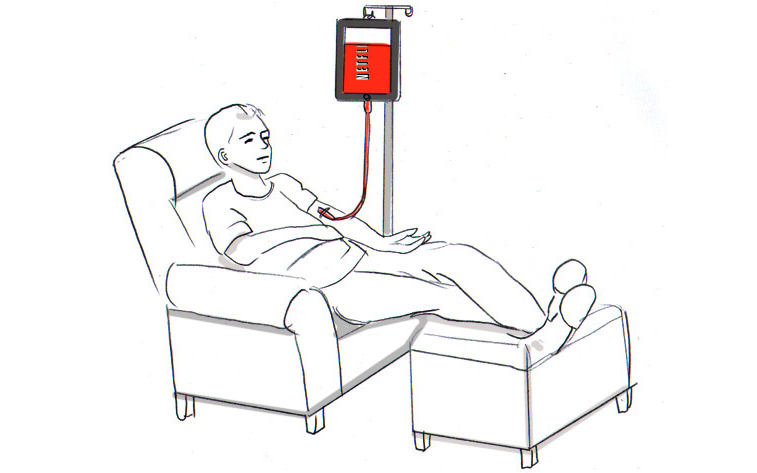

In addition to variations in episode and season structures, Netflix poetics include thematic and stylistic consistencies across programming genres. In my experience of watching *a lot* of Netflix originals, I’ve found that they tend to be particularly metafictional, or self-conscious about storytelling. Many include narrators (Narcos, Jessica Jones), some of whom are able to break the fourth wall (House of Cards, A Series of Unfortunate Events), while others emphasize storytelling-as-such (The OA, Bloodline). Several Netflix originals also feature addiction plots, which, as I’ve argued elsewhere, can be understood as thematizations of the binge-viewing process. Stylistically, Netflix originals share similarities with what many have called “quality TV,” such as higher production values, darker colour palettes, and more “cinematic” camera work. In addition, these series typically assume a dedicated viewer who watches each episode closely, so they do away with many of the recapping strategies typical of broadcast TV, and they don’t use cliffhangers to manufacture hype. Fuller House and The Ranch notwithstanding, Netflix original series seem to be attempting to offer stories that aren’t often told on television.

So, how do Netflix poetics change our relationship to endings? In my previous Flow article, I discussed a pervasive ambivalence that we feel with regards to the ends of TV series. I was speaking particularly about series finales, but that ambivalence is often present in relation to season and even episode endings as well. While there have been relatively few series finales of on-demand native shows (itself a phenomenon in need of more attention), we can still draw some conclusions about the effect of Netflix poetics on our experience of endings.

When we reach the end of an episode on Netflix, the infamous “auto-play” function begins a countdown that gives us roughly 15 seconds to decide whether or not to keep watching. Auto-play is one of the ways that Netflix subverts the power of endings, instantly reminding us that there is more to be watched. Recently, Netflix has extended the reach of the auto-play function, so the closure (or lack thereof) of a season finale is immediately undercut by the start of the next season—if it exists. Anticipation has traditionally served as the central component of TV storytelling, but on-demand viewing limits the opportunities for a series to capitalize on this emotion. When a full season or series is available on Netflix, we control the temporality of endings: we can race to the finale, milk a season for all its worth, or skip right to the final episode. But even as we gain more control over viewing time, we are often so lured by the joys of narrative immersion that we give ourselves over to the addictive flow of a particular series. We binge because we can, but also because it feels good.

On-demand contexts like Netflix divorce endings from the paratextual hype and social buzz that accompanies most season and series finales. Sometimes, as a result of auto-play functions, we may not even realize that we’ve reached a finale. Most discussions about series finales position these episodes as “cultural spectacle[s],” emphasizing the social nature of endings and communal experiences of closure and finality. [2] While we certainly do sometimes watch Netflix with our partners and friends, the ability to personalize viewing temporalities means that, more often than not, Netflixing is a solitary act. We still discuss and share our experiences of a series with others, which is why I disagree with accounts claiming that on-demand viewing diminishes the social nature of television, but there’s no doubt that these technologies change the value and meaning of finales.

As I noted above, very few Netflix originals have ended their series runs. [3] Once we get a proper sample size, it will be interesting to see how Netflix series finales stack up against a history of TV endings. As for season finales, Netflix originals strike a balance between utilizing traditional closural gestures—answering season-spanning questions, setting up the conditions for subsequent seasons—and maintaining stylistic loyalty to the rest of the series. In other words, Netflix season finales don’t tend to stand apart from other episodes to the same extent that cable and broadcast finales do, and so the special pressures of finale storytelling come more from the viewer’s ingrained expectations than from structural narrative imperatives. Personally, I’ve found Netflix season finales less disappointing overall, but nonetheless underwhelming. I’m rarely angered by them, but I’m rarely satisfied. It seems that on-demand viewing emphasizes a drive towards finality by encouraging binge-viewing, but Netflix original series have yet to solve the problem of what it means to make a “good” finale.

Image Credits:

1. Author’s screen grab

2. Letterkenny is the flagship series of CraveTV, a Canadian video on demand (VOD) service3

3. Author’s screen grab

4. Author’s screen grab

5. Author’s screen grab

6. Kiersten Essenpreis’ Netflix Addiction

7. Author’s screen grab

Please feel free to comment.

- These changes in TV poetics are not limited to Netflix, or even to on-demand native series. As Sepinwall points out: “More and more […] dramas are being structured for marathon viewing, rather than the weekly schedule in which they originally air.” In Complex TV, Jason Mittell argues that “Compiling a serial allows viewers to see a series differently, enabling us to perceive aesthetic values traditionally used for discrete cultural works to ongoing narratives” and VanDerWerff notes that binge-viewing “changes everything” about our relationship to a series. In the context of this article, I’m using “Netflix poetics” to describe features of Netflix original series, though I believe that this poetic structure extends to all series that are put into on-demand context. [↩]

- Joanne Morreale (2000), “Sitcoms Say Goodbye: The Cultural Spectacle of Seinfeld’s Last Episode.” Journal of Popular Film and Television. 28.3. 108-15. [↩]

- Hemlock Grove ended after 3 seasons (a planned finale), and Marco Polo was cancelled after two (unplanned). [↩]

The connection between binge-watching and addiction themes in Netflix shows was not one that I had ever thought about. I’m definitely adding The Netflix Effect to my reading list!

Another thing I’m thinking about Netflix “endings” is that when there is no other episode or season available, Netflix will suggest other similar properties for you to watch (if I remember correctly, sometimes it will even start auto playing them). I personally dislike this because the suggestions are always poor and it doesn’t give me any room to experience and dwell on the ending. I’m not sure how others experience this.

Pingback: “HAVE YOU EVER TRIED TO UN-MAKE SOUP?” LEGION’S ROLLER-COASTER RIDE THROUGH THE SIXTIES by Tobias Steiner | CST Online

Pingback: CST Online | “HAVE YOU EVER TRIED TO UN-MAKE SOUP?” LEGION’S ROLLER-COASTER RIDE THROUGH THE SIXTIES by Tobias Steiner

Pingback: Streaming TV & The Future; Final Thoughts – Homework Paper

Thanks for all of this new information. I apricate it