I Am Woman, See Me Bleed: from Tampon Taboo to the Pro-Period Movement

Alexis Carreiro / Queens University of Charlotte

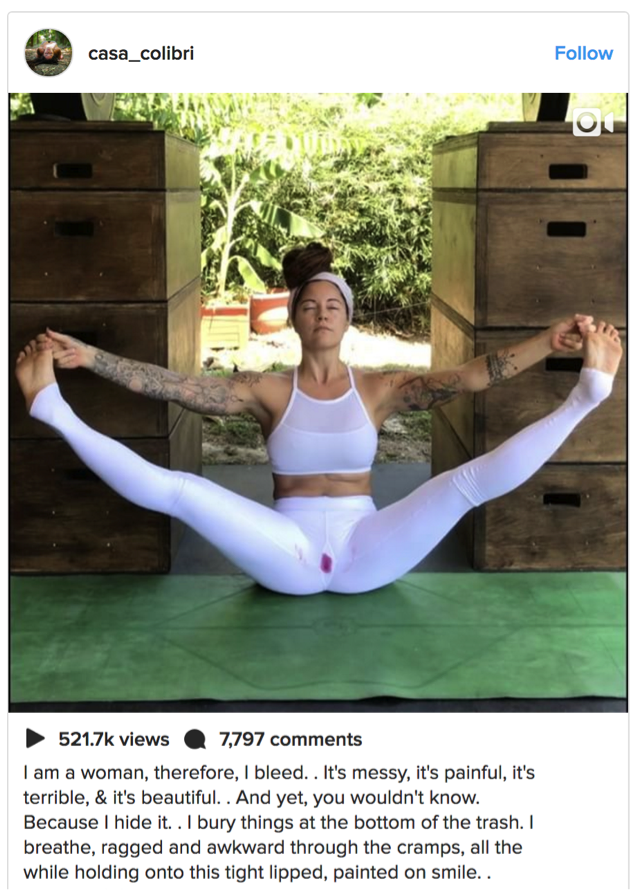

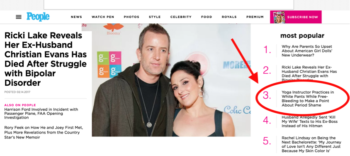

People Magazine isn’t exactly on the cutting edge of feminist sub-culture. In fact, it’s usually the opposite.[1] However, on February 14, 2017 it ran this story online (“Yoga Instructor Practices in White Pants While Free-Bleeding to Make a Point About Period Shame”) and posted the image above. Perhaps more shocking than the image itself is that, according to the homepage, it was the third most popular story that day.

The story features Steph Gongora’s Instagram video of her yoga practice while having her period. However, contrary to People’s headline, Gongora claims that she wasn’t free-bleeding and that it was “just a leak.” [2]

Free-bleeding refers to women who don’t use any menstrual products during their periods. Gongora, on the other hand, seems to imply that her product leaked during yoga. For some women, free-bleeding is a choice while for others, it’s not. In her original Instagram post, she highlights how millions of women around the world lack access to (or can’t afford) menstrual products and the negative impact it has on their lives. She directly relates that to her decision to post the video and encourages women to break free from the shame and embarrassment they feel about their bodies during menstruation. For Gongora, she posted the video of herself in solidarity with women who free-bleed—not by choice but—by necessity.

To date, the post has over 520,000 views and (almost) 8,000 comments that, not surprisingly, are not all positive. They range from supportive and celebratory to callous and contemptible. To put it mildly, the comment section, like the history of the tampon itself (and its history in popular culture), is a bit… messy.

In her article for The Atlantic, Ashley Fetters charts the history of the tampon from its origins in the late 18th and 19th century, and examines the various materials used over the years (like plants, paper, wool, gauze, and glycerin) to aid in absorption. [3] Over the last several hundred years, companies have improved the basic design and are now offering eco-friendly alternatives like “period proof underwear” (Thinx) and various menstrual cups designed to catch the flow, [4] but menstrual blood is still taboo to talk about and, even more so, to show or display on film or TV. For such an ordinary and daily occurrence, it’s largely and—more specifically—visibly absent within mainstream, American media. Or, when it is present, it’s traditionally seen as horrific, comical, or shameful. [5] According to Fetters, “the commercial tampon as we know it has been shaped and re-shaped by a myriad of invisible forces—like genuine concern for women’s wellness, certainly, but also sexism, panic, feminism, capitalism, and secrecy.” Part of what the pro-period movement attempts to do it remove that panic and secrecy. [6]

Over the last several years, all-things-menstruation have gained momentum and visibility outside of broadcast media. [7] People across the world have used social media to protest the “tampon tax” that categorizes menstrual products as luxury items. [8] Some people (women and men) have used social media to de-stigmatize the natural phenomenon. [9] For example, artist Rupi Kaur posted a photo of herself during her period on Instagram.

It was part of a larger photography project her visual rhetoric college course. Instagram originally banned it but later reversed their decision after the outcry on social media. It was in 2015, however, when former M.I.A. drummer Kiran Gandhi ran the London Marathon without a tampon that the movement really gained legs. [10]

She did it for several reasons—one of which was physical comfort and the second was to raise awareness about the relationship between economic oppression and period stigma. According to Gandhi, “My run was about using shock factor to create dialogue around menstrual health and comfort, so that women can start to own the narrative of their own bodies. Speaking about an issue is the only way to combat its silence, and dialogue is the only way for innovative solutions to occur.” [11] And create dialogue, she did. This story was picked up and covered by Buzzfeed, The Daily Mail, The Telegraph, The Huffington Post, The New York Times, Mashable and more. In fact, it helped push the movement so far forward that National Public Radio called 2015 “the year of the period” [12] and Cosmopolitan referred to it as “the year the period went public.” [13]

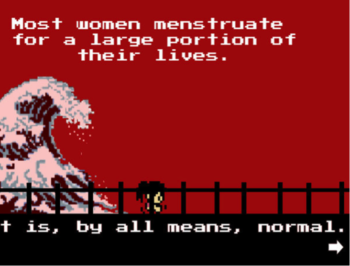

Women, however, aren’t the only ones contributing to the movement. Two teenage girls created a video game called Tampon Run that also went viral and eventually landed them a book deal. In the game, the player has to “collect tampons, shoot them at your enemies, and don’t run out of them before your moon cycle is over.” [14]

Of those whose bodies who are capable, roughly 25% of the female population are menstruating at any given time; that means approximately half the population are bleeding from their vaginas about a quarter of the time. Therefore, there is nothing inherently strange or weird about the biological process. Yet, culturally, it is shrouded in mystery, largely invisible in mainstream media, and remains taboo. This is exactly what Tampon Run is trying to resist. According to the developers, the goal of the game is to “normalize tampons in video games where guns would have been acceptable otherwise.” [15]

And this, to me, highlights the central problem; we live in an era where it is more acceptable to see dead victims of police brutality (on TV or in the news) than it is to see menstrual blood; the menses is more shocking than the murder—and the blood more shocking than the bodies. It is a striking example of how something so ordinary and mundane is actually shocking—and how something so shocking has become so ordinary. [16]

The pro-period movement, with its diverse members from across the world, is only working to solve one part of that problem and, more likely than not (similar to the debate about breast-feeding in public), it will never completely go away. So the question we need to ask ourselves is: whose blood, and in what circumstances, is the most difficult to look at? And, what does that reveal about us as a culture?

Image Credits:

1. Image for “Steph Gongora Free Bleeding Yoga,” People.com.

2. Author’s screenshot; People.com, February 14, 2017

3. Image for “The History of the Tampon,” The Atlantic, June 1, 2015, credited to “ SASIMOTO / Shutterstock / Kara Gordon / The Atlantic.”

4. Rupi Kaur, Artist’s Website.

5. From Kiran’s “modern period piece” on Medium.com.

6. Screen shot from Tampon Run, Fast Company, September 5, 2014.

Please feel free to comment.

- They, like many celebrity publications, often use the words “flaunt” and “showing off” when describing women who are simply in public. Running errands. Going to wok. Playing at the beach with their children. That language perpetuates the idea that women exist to be looked at — and dress as objects for other people rather than subjects in their own lives. [↩]

- You can see the full video and text here. [↩]

- https://www.theatlantic.com/health/archive/2015/06/history-of-the-tampon/394334/ [↩]

- It seems fitting to discuss this topic in a journal called Flow. [↩]

- For a quick overview of film and TV shows from the last 25 years that feature menstruation, see this and this. And, for a great satirical sketch about men’s role during women’s menstruation, see Key & Peele’s Menstruation Orientation. [↩]

- This pro-period movement, of course, isn’t new. This 2015 Bustle article explains the recent history of the movement which most people seem to date back to a 2004 blog post and then chart through 4chan’s 2014 “Operation freebleeding” hoax. [↩]

- Some of the most popular hashtags related to this are: #padsagainstsexim #freebleeding #notaxontampons #justatampon #PeriodsAreNotAnInsult #realmensupportwomen. [↩]

- Larimer, Sarah. “The Tampon Tax, Explained.” Washington Post. January 8, 2016. [↩]

- See Jose Garcia, Instagram, 2015. [↩]

- Here is her first-hand account of the experience. [↩]

- Madame Gandhi Blog. Sisterhood, Blood, and Boobs at the London Marathon 2015. [↩]

- Gharib, Malaka. NPR.org. December 31, 2015. According to this article, “But social media’s been awash with the p-word, and when we checked the number of times the word “menstruation” was mentioned in five national news outlets, it more than tripled from 2010 to 2015, from 47 to 167.” [↩]

- The 8 Greatest Menstrual Moments of 2015. October 13, 2015. [↩]

- Brownstone, Sydney. Fast Company. September 5, 2014. The game creators are not the only females to fling tampons or sanitary products as a form of protest. See A Brief History of Tampon Throwing and A Short History of Women Throwing Their Tampons at You for more information. [↩]

- Brownstone, 2014. [↩]

- International artist Elone is also tackling this concept in her work. [↩]