Robots in Popular Culture: Labor Precarity and Machine Cute

Anthony P. McIntyre / University College Dublin

In August 2015, Hitchbot, a robot developed by academics at McMaster and Ryerson Universities in Canada, was vandalised beyond repair in Philadelphia just 4 days into its mission to travel across the US depending on the kindness of strangers. A video promoting the robot’s earlier successful hitchhiking adventure across Canada introduces Hitchbot’s developers by cheerfully announcing that “Usually it’s humans that are scared that robots will take over the world, well these guys flipped that idea on its head.” [1] However, later events would of course undermine the vision of benign human robot collaboration that informed the road trip experiment. While the true motive behind the vandalism that cut short Hitchbot’s journey is impossible to know for sure, the whole episode is evidence of the highly ambivalent positioning of robots in popular culture, and a suspicion of these technological marvels. This ambivalence, I argue, is compounded by the affective responses generated by cuteness, one of the main aesthetic paradigms for the representation of robots. Cuteness, in the view of some theorists, with its aestheticization of weakness or powerlessness, also generates feelings of suspicion and exploitation that can trigger violent responses. [2] In addition to the demise of Hitchbot, we may also consider the “Burning Elmo” videos posted on YouTube, [3] where the lovable cute talking toy is burnt, while often continuing to talk as exemplary of this phenomenon.

Cuteness was initially theorised by ethologist Konrad Lorenz, who in 1943 developed a kindchenschema, or ‘child schema’ that posited features such as large eyes, pudgy extremities and clumsy movements as common to infant humans and animals alike. Lorenz ‘s belief was that such features triggered nurturing behaviours in adults and were part of an evolutionary step to ensure caregiving for the young of a species. Many contemporary theorisations of cuteness contest some of Lorenz’s more rigid views on the links between cuteness and an instinctive nurturing response, with psychologists Gary D. Sherman and Jonathan Haidt, for instance, suggesting that the response elicited is more often one of play rather than protection. [4] Machine cute exists within a constellation of both visual and behavioural traits that overlap with but also go beyond Lorenz’s kindchenschema. The main features of machine cute are (a) overt indicators of vulnerability, such as clumsiness; (b) a lack of bodily integrity; (c) limited linguistic capacities; and (d) a naivety or cognitive neoteny. Examples of machine cute can display several of these features, but not necessarily all, as I shall demonstrate.

If we consider recent examples of robots that emerge in contemporary popular culture, BB8 in Star Wars: The Force Awakens, (2015) Baymax in Disney’s Big Hero 6, and Chappie the eponymous robot from Neil Blomkamp’s 2015 violent action adventure film, we can see differences in how machine cute manifests. All three of these robots, as well as, of course, Hitchbot, demonstrate key features of machine cute to a greater or lesser extent.

With Hitchbot, for instance, we see in his ultimate demise evidence of his lack of bodily integrity. The robot had limited linguistic capacities and was a less than robust entity, commonly requiring reassembly on his travels, even before he met a violent end. In Chappie, although the robot was originally built as part of a generic squad of humanoid police robots, from the beginning of the film this particular robot is portrayed as vulnerable to attack, signified visually by a prominent replacement bright orange ear. This aspect of machine cute marks the seeming opposite of the impenetrable robot impervious to human attack common to dystopian sci-fi narratives, a type perhaps best represented by Gort from the classic 1951 sci-fi The Day the Earth Stood Still.

Chappie’s cuteness really emerges with his “birth” scene, briefly shown in the trailer below, with the robot displaying the cognitive neoteny of a human infant in its early years, although considerably accelerated. Chappie’s linguistic development improves quickly also but for most of the film his grammar is imperfect, with the robot referring to himself in the third person, using tenses clumsily, saying lines such as: “Chappie got stories” and “Chappie got fears.” This demonstrates how the depiction of robots as cute on the basis of linguistic incompetency works similarly to the aesthetic process that cute-ifies animals as demonstrated in the iconic “I can haz cheezburger” meme.

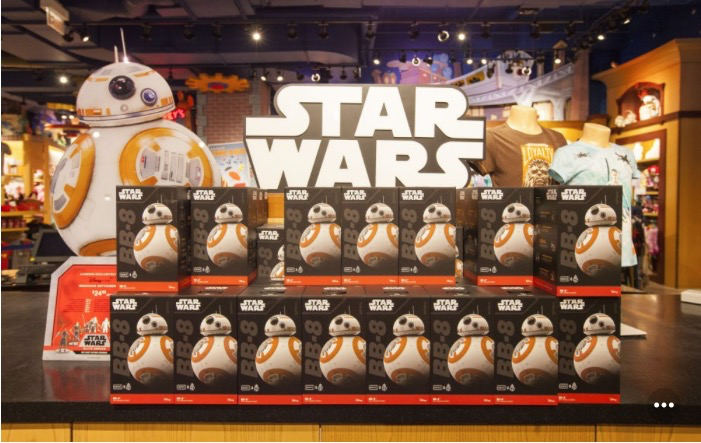

Prior to the release of Star Wars: The Force Awakens, a toy version of BB8, the cute round robot that assists the central characters just as R2D2 did in the early movies, hit the shops. BB8 both as character in the film and as a toy, demonstrates key features of machine cute. The video below of the BB8 toy designer providing a demonstration also suggests the pedagogic role such material objects perform [5] .

If we apply the criterion of limited linguistic capacities, it seems congruent with the case of BB8 with its complete lack of intelligible words and reliance on affective-digital sounds that indicate mood. In addition, we see vulnerability inherent to the little robot, both on account of its diminutive size and its tendency to dismantle easily with the head popping free of the body in instances of minor collision. Finally, we might consider the concept of labour as articulated by the robot engineer. His various statements bear analysis. While acknowledging the existing fears about robots (he’s careful to distance the robot from notions of surveillance), he makes the contradictory remarks that it’s not there to do anything and later suggests the toy constitutes “the first step to people being used to having robotic companions,” for which we should also read, perhaps, robotic labour.

In effect, this robot, and the many similar toys and devices that flooded the market in its wake are there as pedagogical instruments. So, much in the same way that Joyce Goggin, building on the material cultures work of Daniel Miller, describes the Liddle Iddle Kiddle dolls she played with as a child and collects as an adult as providing a means of teaching “how to perform gender in a very essentialized … way,” [6] the BB8 robot seems to be facilitating interaction with a robot companion while simultaneously alleviating the fears that would surround such technologies.

If Hitchbot, Chappie and BB8 are a far cry from the haptic sensuality of what many associate with cuteness, such as the furry softness of puppies and kittens, there are also examples of machine cute that align with these features. Writing on plush toys in his analysis of cuteness as a commodity aesthetic, essayist Daniel Harris (2000) describes “… a world of soothing tactile immediacy in which there are no sharp corners or abrasive materials and in which everything has been conveniently soft-sculptured to yield to our importunate squeezes and hugs.” It is such a world that Baymax, the robot star of Big Hero 6 clearly belongs to. Of all the robots I consider, the medical robot from this movie is perhaps the most “classically” cute. His softened and rounded body constitutes an extreme end point in animated figurations of cuteness. His soft features also contribute to the robots clumsiness (see gif) (another key element feature on the machine cute schema). I ’m not sure how much further you could go in terms of soft lines and rounded features without losing discernibility. This over-determined cuteness, I argue, functions in one way to obfuscate the very real threat presented by robotic labour to large swathes of the working population.

It has been widely predicted that as robot costs decline and technological capabilities expand, robots are expected to replace human labour in a wide range of low-wage service occupations. In an Atlantic article, “The Fastest-Growing Jobs of This Decade(and the Robots That Will Steal Them),” for instance, the author notes that the low-wage sector is the area where most US job growth has occurred over the preceding decades and in fact many people had been shifted down to such jobs as higher paid employment shrunk as a result of automation. [7] This means that many low-wage manual jobs that have been previously protected from technological developments such as automation could diminish over time, leading to large-scale expulsions from the labor force and increased numbers living in poverty. In addition, many studies predict that highly skilled jobs such as those related to healthcare face a similar threat from automation and robotic labour. [8] In Baymax, we have a fictional medical care robot who can perform the functions of a physician and a personal care aid — two of the professions indicated as being under threat. The suggestion that Baymax was inspired by developments in “soft robotics” [9] attests to the bi-directional influence that fictional and real life robots exert on one another, and while such robots are demonstrably a long way off, technologies providing similar services are not too far away.

As Annalee Newitz notes in her book Pretend We’re Dead: Capitalist Monsters in American Pop Culture (in which she argues that robots are one such example of capitalist monsters) considerations of labour relations are rarely the main focus in popular film, yet often “lurk in the background, shaping the narrative.” [10] In Big Hero 6, this is certainly the case, but with Neill Blomkamp’s short film Tempbot (2006) we have a not entirely successful attempt to examine the potential impact of robotic supplantment of human labor. [11]

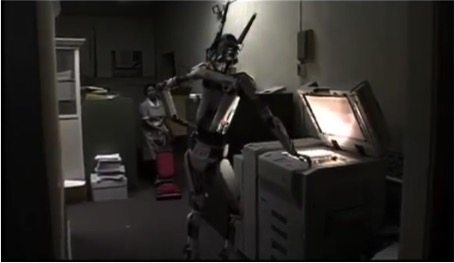

Tempbot, as the title suggests, concerns the eponymous machine (an earlier version of the robot that would appear in Chappie) which is, brought into a cubicle office environment as a temp worker, where it is largely ignored by the rest of the mostly disaffected workforce. The short film is somewhat uneven and the cringe humor it attempts is heavily indebted to Ricky Gervais and Stephen Merchant’s comedy The Office (2001-03). The vulnerability of the robot in this film is primarily figured through his romantic infatuation with a recently hired female manager and consequent inability to navigate the complex rules of (human) inter-personal intimacy.

If we examine the screenshot below we see an example of how cuteness, as I argued in my previous Flow column, functions in proximity to subordinated groups. Tempbot suggests that there is complacency among those at a more senior positions in the workplace hierarchy, while the ethnic-minority depicted cleaners — here warily watching as Tempbot continues working long after his colleagues have departed for drinks — are those most aware of the threat posed by the new workplace paradigm the robot constitutes.

At the end of the film, the office is shown completely staffed by Tempbots and, given the evident unhappiness of most of the human workforce depicted in the film, it is unclear whether this is to be interpreted as a happy ending or not. One strange aspect of the film is the dual function of Tempbot who both functions as metaphor for alienated labour and the increased pressures of post-Fordist working conditions, what Melissa Gregg has termed “workplace affects in the age of the cubicle” as well as the threat roboticized labour presents to employees in such disaffected workplaces [12] . The lack of clear interpretation is quite fitting given the ambivalence of cute robots in general, which both move us emotionally through their vulnerability but also are indicative of very real threat to many livelihoods.

Image Credits:

1. Facebook

2. Courtesy of the author.

3. Youtube

4. The Guardian

5. ibid.

6. Giphy

7. Screenshot from Tempbot (2006) courtesy of the author.

Please feel free to comment.

- “https://www.facebook.com/greatbigstory/videos/1610167969285630/“ [↩]

- “Ngai, Sianne. Our Aesthetic Categories: Zany, Cute, Interesting. Cambridge, Mass. and London: Harvard UP, 2012. Print.” [↩]

- “https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NKTlVIKd6hw“ [↩]

- “Sherman, Gary D., and Jonathan Haidt. “Cuteness and Disgust: The Humanizing and Dehumanizing Effects of Emotion.” Emotion Review 3.3 (2011): 245–51.” [↩]

- “Gibbs, Samuel, and Richard Sprenger. “Meet BB-8, the Star Wars Droid You Can Take Home as a Toy – Video.” The Guardian. Guardian News and Media, 03 Sept. 2015. Web. 22 Feb. 2017.” [↩]

- ” Goggin, Joyce. “Affective Marketing and the Kuteness of Kiddles” in The Aesthetics and Affects of Cuteness, ed. Joshua Paul Dale, Joyce Goggin, Julia Leyda, Anthony P. McIntyre and Diane Negra. New York: Routledge, 216-34.” [↩]

- “Thompson, Derek. “The Fastest-Growing Jobs of This Decade (and the Robots That Will Steal Them).” The Atlantic. Atlantic Media Company, 28 Jan. 2014. Web. 22 Feb. 2017.” [↩]

- “Susskind, Richard, and Daniel Susskind. “Technology Will Replace Many Doctors, Lawyers, and Other Professionals.” Harvard Business Review. N.p., 31 Oct. 2016. Web. 22 Feb. 2017.” [↩]

- “Ulanoff, Lance. “‘Big Hero 6’ Star Baymax Was Inspired by a Real Robot.” Mashable. Mashable, 07 Nov. 2014. Web. 22 Feb. 2017.” [↩]

- “Newitz, Annalee. Pretend We’re Dead: Capitalist Monsters in American Pop Culture. Durham: Duke UP, 2006. Print.” [↩]

- “Swedish TV series Äkta människor (trans. “Real Humans,” 2012-14) and its UK/US remake Humans (2015–) have recently taken a more sustained look at the issue. For an analysis of cute robots that examines specifically female-gendered and sexualized robots and analyzes these series, see Julia Leyda, “Cute Twenty-First-Century Post-Fembots” in The Aesthetics and Affects of Cuteness, ed. Joshua Paul Dale, Joyce Goggin, Julia Leyda, Anthony P. McIntyre and Diane Negra. New York: Routledge, 151-74.” [↩]

- “Gregg, Melissa. “On Friday Night Drinks: Workplace Affects in the age of the aubicle.” In The Affect Theory Reader (2010) ed. 250-267″ [↩]

i am always surprised what will happen to work of Humans once Robos come into human life

Very unorthodox real life rollercoaster ride of comedy at its finest yet weirdest 😶🤔😝

Pingback: Am I a New Medium? – SoPHIA'S REAL LIFE