TV Finales: Breaking Up is Hard to Do

Casey J. McCormick / McGill University

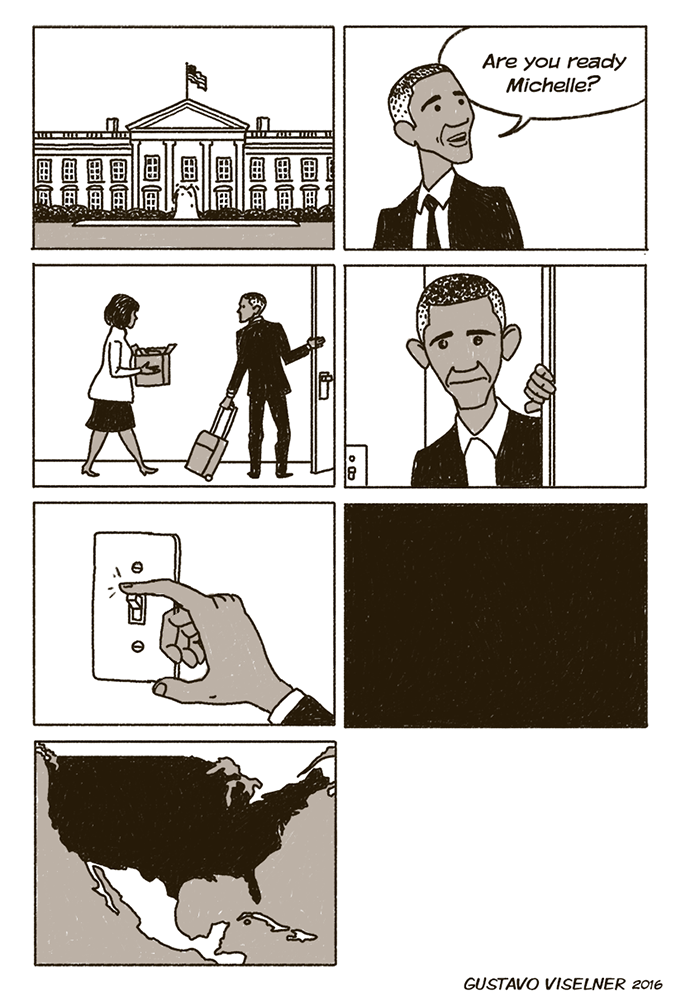

Last week, President Barack Obama delivered his Farewell Address, and many viewers expressed emotional reactions to the broadcast via social media. I was fascinated by the number of tweets comparing the event to watching the finale of a fictional TV series. While some of these comments were clearly sarcastic, in many cases, the comparison between this political address and fictional finales expressed a deep emotional experience — one of loss, heartbreak, and grief. Similarly, the above comic strip uses a familiar TV finale trope (turning out the lights on an empty sitcom set) to convey the existential darkness of a Drumpf America. This response to #ObamaFarewell shows that our engagement with longform storytelling can impact how we structure other parts of our lives — in particular, how we resist endings and manage loss.

The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air, “I, Done, Part 2” (1996)

The numbers show that audiences care about TV endings. Super Bowls (“finales” of the NFL season) and series finales of fiction-based programming make up the vast majority of most-watched TV broadcasts in US history. [1] Even floundering or failing shows often see an increase in viewership for their series finales, with viewers who have otherwise divested themselves from a show tuning in just to see how things turn out. And popular shows usually see an uptick in live viewership, highlighting our desire to experience finality as a viewing community and, more practically, to avoid spoilers. Meanwhile, finales are some of the most criticized episodes of TV, with “disappointment” and “anger” being two of the dominant responses to this category of episode. Over the past few years, I’ve been working on a dissertation project that examines TV finales from historical, formal, and experiential perspectives. Here, I’d like to share some of the key points from my research regarding why finales matter, and how audiences express an ambivalence regarding the ends of longform TV storytelling.

In 1957, a review of The Nat King Cole Show finale stated: “From now on six thirty pm will seem strange until we come to realize other programs can be good.” [2] This quote demonstrates that finales have been important for most of TV history. Even in the case of musical variety shows, talk shows, and episodic shows like sitcoms or procedurals, “the end” is fundamental to our viewing experiences. [3] But as TV storytelling has become increasingly complex and serialized, finales have taken on a more significant role — for many shows, finales are often the terrain upon which a series fails or succeeds, and these episodes can spark intense emotions — positive and negative — in TV viewers.

Structurally, TV finales tend to: be longer than the series’ average episode, include flashbacks and/or flashforwards, and feature a marriage, death, or change in vocational status for one or more main characters. It rarely behooves creators to close off a storyworld completely, so most finales attempt to strike a balance between closure and openness to satisfy viewers but keep the storyworld malleable, setting up potential spinoffs and/or inviting fan engagement. The patterns that emerge in analyzing TV finales across a wide range of genres suggest that we are aware of similarities across texts, and these conventions create expectations about what TV closure should be. Jason Mittell writes of the pressure on long-arc serials to “stick the landing” in series finales, but I am equally interested in the pressures we feel as viewers when confronted with the end of a beloved series. [4]

Our ambivalence towards TV endings goes something like this: we want our questions answered, we want to feel a sense of closure, of satisfaction, but we also don’t want the story to be over. We want the world to continue to exist — in particular, we want the characters that we’ve grown to love to keep on existing. But we also enjoy being surprised, even shocked, by a significant death or major plot twist. Our attachment to a TV narrative comes through its characters, so killing someone off is an easy way to garner an emotional reaction and instill closure. In a series focusing more on a single character than an ensemble, killing the main character also generates closure through synecdoche (e.g. Tony Soprano’s death = the death of The Sopranos). Meanwhile, “twists,” at their best, offer a thought-provoking surprise; at their worst, they betray the entire storyworld and undermine the potential for satisfying closure. Indeed, some of the most controversial finales are considered so because of dubious plot twists.

Responses to finales vary based on our individual experiences with a particular show, or with TV more generally. They vary based on our social, religious, and political beliefs. And they vary based on our specific circumstances of viewing (for example, someone who binge-watches vs. someone who dedicates years of incremental viewing time). But when we really care about a show, the conflicting desires for closure and openness and the intensity of emotion when we reach the conclusion emerge as common denominators in our experience of TV finales.

There was a fascinating trend in the Tweets comparing #ObamaFarewell to fictional finales: people claiming that they weren’t watching the address, just as they couldn’t bring themselves to watch the finales of much TV fiction. Casual polling revealed that this practice is far more common than I’d imagined: on Facebook and Twitter, I received dozens of testimonials from people who deliberately resist finales out of the desire to end a series on their own terms, to spare themselves disappointment at a lackluster finale, or because they just find the experience of finales too sad. This resistance to TV endings is evidence of the power of finales and our ambivalent attitude towards closure and finality. In many ways, our attachment to a TV series feels like a romantic relationship: we invest time and energy, go through ups and downs, threaten to quit, get sucked back in…lather, rinse, repeat. But like any relationship, breaking up with a TV series is hard to do — especially when you’re the one getting dumped.

Image Credits:

1. Cartoon of the Obamas’ final day in the White House

2. Friends, “The Last One, Part 2” (2004)

3. The Mary Tyler Moore Show, “The Last Show” (1977)

4. The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air, “I, Done, Part 2″ (1996)

5. “Lay Down Your Burdens, Part 3” (2009), the finale of Battlestar Galactica, contains a massive temporal jump that angered many fans

6. In “The Last One” (1988), St. Elsewhere reveals that the show’s six seasons have been taking place in the imagination of autistic child, Tommy Westphall

Please feel free to comment.

- For the most part, these are instances of planned finales, in which TV creators know that an episode will be the series’ last. In this article, when I refer to “finales,” I’m referring to planned finales. [↩]

- The Chicago Defender, 28 December 1957. [↩]

- Perhaps the biggest exception to this rule would be soap operas, which thrive on their ability not to end. [↩]

- Complex TV: The Poetics of Contemporary Television Storytelling. NYU Press, 2015. Pg. 322 [↩]