#TrumpIsRight: The Paradox of Digital Database Histories and Collective Memory

Eric Hahn / New York University

The Internet has served as a catalyst for the development of interactive and shared historical archives. Websites and databases like Immigrant Nation and CNN’s iReport, have approached what can arguably be understood as the democratization not only of access to historical archives but, and more significantly, to the very creation and curation of history itself. These seemingly open databases where users can effectively craft and post their own historical fragments (be it news or life stories) from unique perspectives calls into question any cohesive, teleological readings of history. While this fragmented and personalized approach to history is seemingly effective in the destabilization and questioning of dominant and often problematic historical narratives, the promise of purely democratic and multifaceted database approaches to history raises alternative and significant questions. This brief article intends to explore the progress and limitations of this digital database approach not merely in its ability to offer central spaces for collective and personal histories, but additionally in regards to the possibility or impossibility of generating “believable” and “substantial” histories. By analyzing the aforementioned sites/databases, one can begin to deconstruct and question the often over-sentimentalized prospect of participatory and democratic constructions of history and collective memory via new and emerging media.

Both iReport and Immigrant Nation function as repositories of “lived” experience. By providing basic information (e.g. name, email address, etc.) or simply linking to a source via hashtag (#CNNiReport) users are invited to post newsworthy items in the case of iReport or personal accounts of emigrating to the United States in the case of Immigrant Nation. While these two sites differ dramatically in terms of business structure (iReport being a for-profit endeavor) this difference ultimately factors little into the nature of the material stocking the databases. Indeed, a quick review of current CNN iReport stories reveals contentious and clearly unmoderated headlines at odds with the traditional fare offered by “the most trusted name in news” such as, “Will Black Lives Matter Team Up with Isis to Stop the Republican National Convention?” and a short, clearly doctored, video titled “Unexpected Jihad” in which a child on a playground explodes. While this lack of moderation seems contradictory, Devon Bissonette rightly suggests, “As long as advertising is linked to user views, media companies have a vested interest in pushing users to generate inflammatory versus informative content, as long as the former proves more salable” (394). [1]

In essence, both for-profit and not-for-profit models can be understood as utilizing fairly loose modes of moderation (of course this varies by website) albeit based on fundamentally different motives: for-profit to generate views, not-for-profits to allow for as many disparate voices to be heard as possible. Hidden within this seemingly revolutionary model in which moderation is limited or non-existent, lies a problematic paradox. In analyzing approaches to database histories that are wholly user moderated, or not moderated at all, any conception of historical “truth” is itself an impossibility. Admittedly, one could argue that historiography is a process of negotiated and mediated readings of reality therefore “truth” is inherently a problematic word. But, such an understanding ignores the fact that traditionally generated histories can theoretically be deconstructed through questioning and contextualizing the source(s) of specific histories. In essence, even problematic historical narratives can be traced (some more effectively than others) and through this process of investigation, inverted, reformulated, or challenged. Conversely, the allowable anonymity of the Internet acts as both a cloaking device for the source of the historical fragment thus problematizing deconstruction and simultaneously a means of separating the creator of a historical narrative from the consequences of such a narrative. Such an approach to wholly democratic databases can be dismissed as too pessimistic, but in briefly pointing to a seemingly innocent post on Immigrant Nation (see below), one can begin to understand the grounds for this critique.

In a post titled, “bjfdbj” by Edgar, we learn of someone who emigrated from Guatemala to the U.S. to escape civil war. Interestingly, the post itself has a picture of a carrot, followed by a seemingly random string of text. While this is certainly nothing alarming or offensive it does pose some important questions. Are the incoherent aspects of this post simply a result of a genuine user having difficulties manipulating the interface or is this perhaps a user who is simply testing or playing with the interface itself? This of course would precede the question: if this is a user simply testing or playing with the interface, can the history documented be given any credence? Again, one can assert that history is fundamentally polylogical and relative but, the anonymity afforded through digital mediation negates any possibility of tracing contextual threads that might allow for the deconstruction of the specific historical discourse. This argument points to a paradox. The Internet has allowed for disparate groups or individuals to connect and share personal or collective histories effectively questioning and destabilizing dominant historical narratives, but, the very medium that enables such a connection fundamentally problematizes the histories generated by its users. As such, the pluralization of the archives’ nomos — the law of the archive and the authority to archive [2] — fractures any tenuous points of contact between truth and history even as it allows for a more diverse and inclusive approach to historiographical practice.

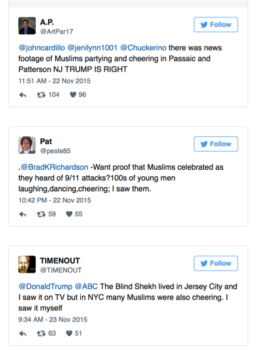

What is significant when analyzing this paradox is not necessarily the loss of grand historical narratives as such, but rather the reverberations of this destabilization. In “Past Indiscretions: Digital Archives and Recombinant History,” Steve Anderson argues that beyond the possibility of total and encyclopedic approaches to history, the significance of the digital and collective approach is the existence of “recombinant histories.” [3] Anderson suggests, “A more provocative historiographical argument is posited in the premise of the apparatus that encourages audience members to lie—to pose as someone other than themselves—in order to generate alternative histories” (110). Anderson expounds the democratic possibility of challenging dominant histories but what is at stake here is not simply the existence of dominant historical narratives — which should indeed be questioned — but additionally the very notion of historical “truth” as relevant at all. One need only turn to contemporary political discourse to witness this (post)modern, Baudrillardian mode of existence. Specifically, presidential hopeful Donald Trump fairly recently claimed, “Hey, I watched when the World Trade Center came tumbling down. And I watched in Jersey City, New Jersey where thousands of people were cheering as that building was coming down.” [4] Vehemently argued as a fictional account by most accredited media and news outlets, this alternative history has no doubt generated concurrent reports even leading to the creation of the hashtag #TrumpIsRight. The pseudo-news website InfoWars dedicated a page to scrolling user generated histories — much like iReport’s “database” — detailing these “celebratory displays” in agreement with Trump’s arguably false historical narrative. [5] As such, Trump’s account, although largely contested, is also forcefully supported through digital “eyewitness” channels whose users fundamentally disavow contrary reports as biased or false.

In essence, the digital archive functions in an interesting way. Rather than envisioning it as a Foucauldian heterotopic paradigm where “time is accumulated but not lived,” we can begin to conceive of this digital approach as “an eminently social practice, a veritable living memory” (254). [6] It is in this vein that Pinchevski argues that this process of digital and user generated historical archives returns the notion of “collective memory” to a kind of pure existence as “the remembering community and the collective will to remember” (256). [7] While one can indeed approach these digital databases as forms of unmediated collective memory, Pinchevski ignores or misinterprets the results of these newly generated mass histories (collective memories). Specifically, collective memory and history itself has reached a stage of pure simulacra. No longer do grand historical narratives exist to be deconstructed and analyzed, but rather, the digital database, in all its democratic potentiality, has indeed served to destabilize and democratize collective memory and history. In this new egalitarian model, all history exists in a dual state: unquestionably true and absolutely false with no room in between.

Image Credits:

1. Donald Trump

2. “Unexpected Jihad” from CNN iReport

3. “bfjdbj” from Immigrant Nation

4. Eyewitness testimonies reported via Twitter

Please feel free to comment.

- Bissonette, Devan. “A Digital Democracy or Twenty-First-Century Tyranny? CNN’s iReport and the Future of Citizenship in Virtual Spaces.” DIY Citizenship: Critical Making and Social Media. Ed. Matt Ratto and Megan Boler. Cambridge: MIT Press, 2014. 385-401. [↩]

- Pinchevski, Amit. “Archive, Media, Trauma.” On Media Memory: Collective Memory in a New Media Age. Ed. Motti Neiger, Oran Meyers, and Eyal Zandberg. Palgrave Macmillan UK, 2011. 253-264. [↩]

- Anderson, Steve. “Past Indiscretions: Digital Archives and Recombinant History.” Transmedia Frictions: The Digital, the Arts, and the Humanities. Ed. Marsha Kinder and Tara McPherson. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2014. 100-114. [↩]

- Taibbi, Matt. “America is Too Dumb for TV News.” Rolling Stone. Rolling Stone Magazine, 25 Nov. 2015. [↩]

- Watson, Steve. “I Live in Jersey and Trump is Right: Muslims Did Celebrate on 9/11 in NJ… We Saw It!” InfoWars. Free Speech Systems, LLC. 24 Nov. 2015. [↩]

- Pinchevski, Amit. “Archive, Media, Trauma.” On Media Memory: Collective Memory in a New Media Age. Ed. Motti Neiger, Oran Meyers, and Eyal Zandberg. Palgrave Macmillan UK, 2011. 253-264. [↩]

- Pinchevski, Amit. “Archive, Media, Trauma.” On Media Memory: Collective Memory in a New Media Age. Ed. Motti Neiger, Oran Meyers, and Eyal Zandberg. Palgrave Macmillan UK, 2011. 253-264. [↩]

Great post