Three Wishes for Flow

Christopher Lucas

Flow started, like a lot of interesting things, from an admixture of naiveté, discontent, and ambition. At least, that is how I remember it. Most people have probably heard some version of the origin story: Avi Santo and I in the back of a meeting room at SCMS, complaining about how the conversations in the hallways were more interesting than what was happening on the dais. The question was: how might we get those conversations into the room? Or maybe we just create a space online to encourage those conversations. And that led to Flow.

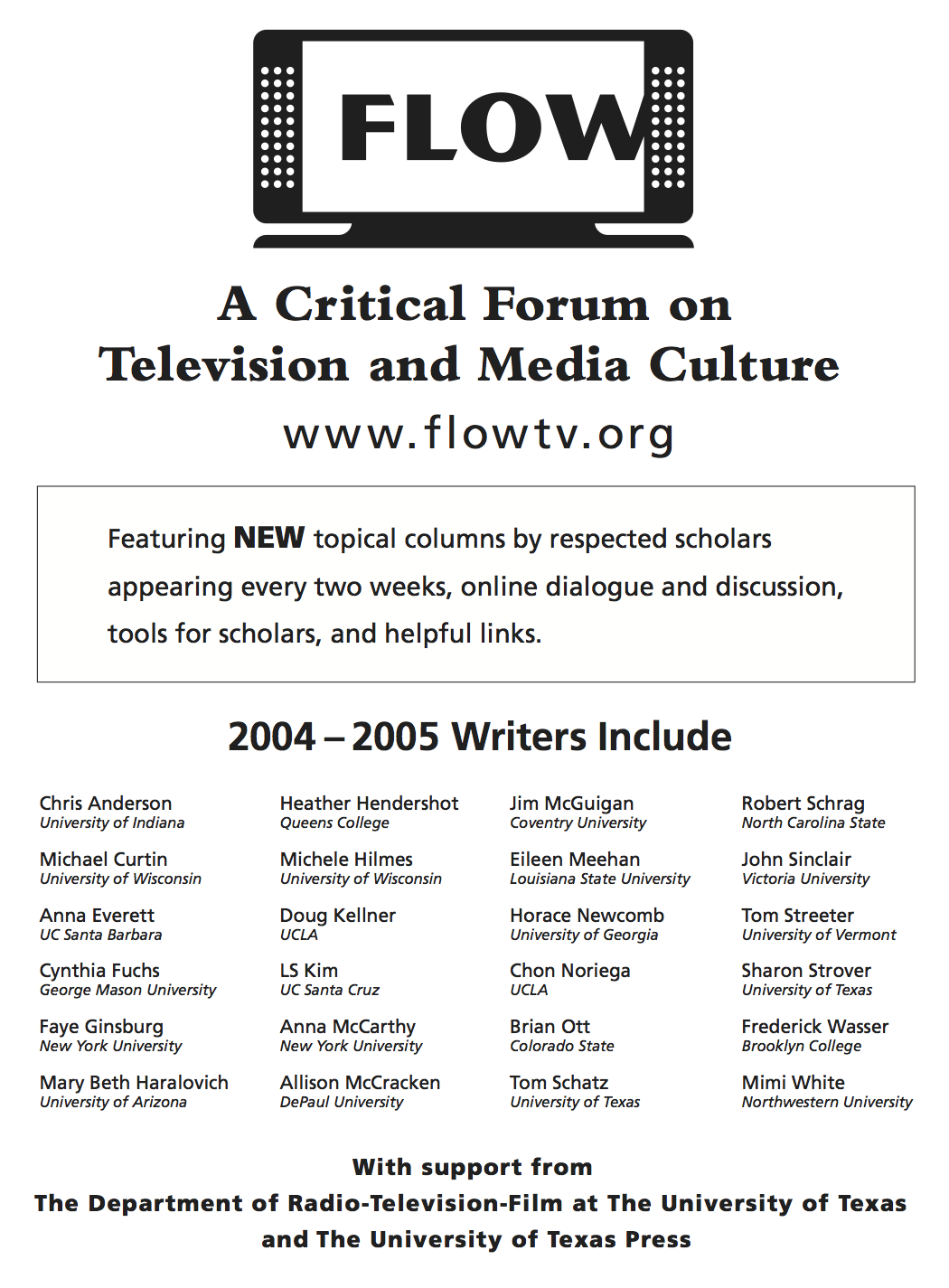

Which, frankly, has survived and thrived for about twice as long as I expected, thanks to the enthusiasm and support of the RTF department, along with the efforts and curiosity—and ambition—of the graduate students here. Your delight in reading your colleagues’ thoughts—maybe using them in class. There is no doubt in my mind that, back in 2004, without contributions from some well-known names in our field, offered to us generously and in the spirit of disciplinary exchange—and perhaps, ambition—the site would not have taken root. Kidding aside, we really owe thanks to those first writers.

That year—2004—some of us might remember, was blogging’s big moment. Blogs were my main reference point—sites with the energy and verve of Daily Kos and Television Without Pity. Movable Type and Typepad had been out for a while, WordPress had launched, it seemed like everyone was Livejournaling. Lots of new verbs. I wanted to hear the blog-thoughts of people I was meeting or reading—and short-form online seemed a natural place for it. Looking back, I can see there were disciplinary currents—a rising interest in responding to contemporary texts, interactivity, fandoms, new media industry practices—that supported the appearance of more ad hoc writing platforms. I really am not the best person to describe that genealogy, though, so instead of diagnosing the past I want to offer three wishes for the future of Flow:

1) I hope Flow continues to model bridge-building toward media practice—practitioners as contributors and/or practice as a object of study. One of my unrealized goals for the site was to link that divide within the RTF department and many departments like it—the gap between studies and production. This goal—I admit—was born of my own pathological hope of healing a divorce in my professional lineage—media maker or media scholar? That split was readily apparent in my research as well, if you want to go looking for it. I know we have professors and instructors out there making films, documentaries, podcasts and more for audiences outside the academy, either directly or by supervising student production, radio stations, and the like. Unfortunately I know a lot of that work remains an add-on—the “personal project”—and doesn’t play much role in promotion and tenure. Maybe this is changing and I hope so. The pedagogical arguments for this sort of boundary crossing—media literacy through media making—still seem valid to me, and recent work in media industry studies and management studies is providing more theoretical arguments and historical perspectives, too.

2) However, my argument for including media makers—by which I mean people who are, or hope to be, paying their mortgages, childcare, or just the next cup of coffee with media industry money—is more about process than content. Another inspiration for Flow, from my side, came from retreats I had attended in the 1990s using the so-called “Open Space Technology,” agenda-less meetings that used techniques of self-organization to find latent order and energy in a work team that shared some mission or interests. Open Space was one of the threads that led into Unconferencing and Bar camps—it is still in the structure here when we submit questions and responses, rather than papers. Wild cards are important in Open Space events: the possibility to surprise, to shock, to break convention. And this often comes from outsiders. So, my second hope for Flow is that it finds even more Open Space in the future. One of my short-lived projects at Flow, called “Pass the Remote,” was a brief attempt at this—pen-palling three academics just to see what happened. In retrospect, when Flow started, our reliance on those leading lights in media studies to get attention—your attention, your department’s attention, our future employers’ attention—created an unintended consequence: arguably, we just re-created an existing hierarchy of topics, methods, and values in a more informal framework. For better or worse, we recreated the discipline, writ smaller and a little woolier. Naïve, I know, but this surprised me.

3) So that’s my third hope for Flow. That it finds ways to challenge disciplinarity. This may be a faint hope. But who could we have here that would disturb notions of media studies as a discipline? I know there is cross-pollination and diversity in your topics and approaches, but what would the shock of Open Space look and feel like at Flow? Scholarship we don’t recognize from people we don’t know. I don’t know if media makers and media executives are the best source of the unexpected, but they might be a start. Other departments. Production students. People using video or the web as their medium for other art forms and political projects. And how would you attract people like that—people with other priorities—mortgages, but no conference stipend? I never cracked that nut while I was involved with Flow. Maybe you show their work. Probably you have to pay them. You definitely have to go looking, because they are no less creatures of ambition than us, and spending three days—or one day—on a college campus holds no particular appeal. I guess what I’m saying is, I think there are fruitful connections to be made when we plug into and discover the naivety, discontent, and the ambitions of others. Unexpected things happen. I’d like to see that.

Image Credits:

1. Flow 2016 logo.

2. A 2004 flyer for FLOW (journal document).

3. Three wishes for Flow…

4. Ethan Thompson’s TV Family…

5. “Open Space Technology”…

Please feel free to comment.